PCE, Income & Outlays: Calendar Gap Closing

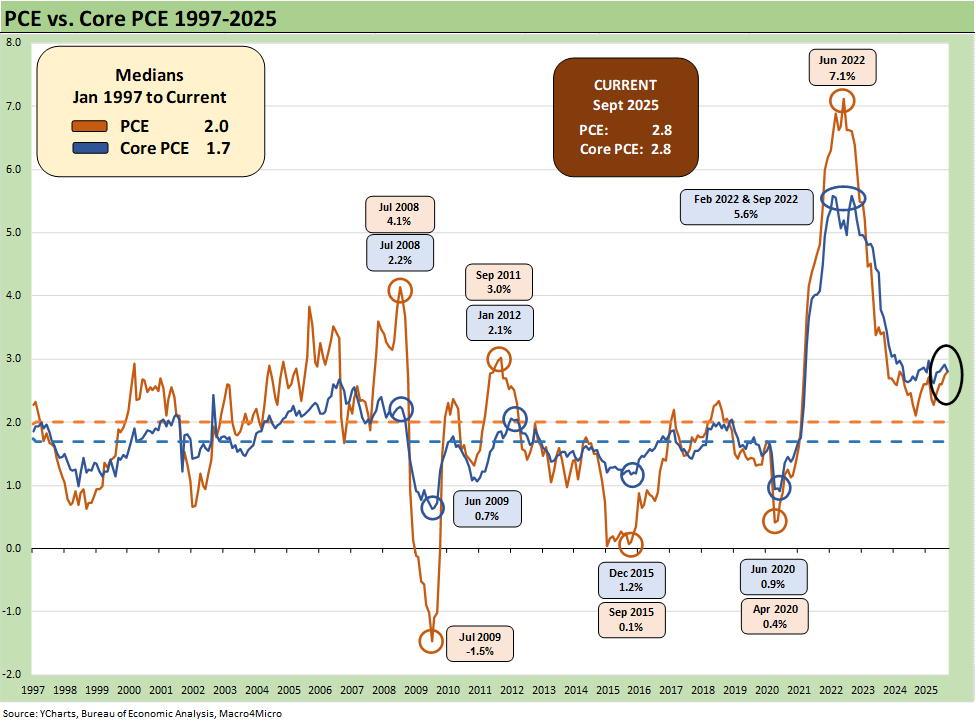

The Headline and Core PCE inflation both at +2.8% is unexciting, but some MoM and YoY lines in Goods, Food, and Energy are concerning.

Time Jump: We are now back in Sept 2025

A relatively benign set of Sept numbers for PCE inflation still leaves headline PCE inflation and core PCE +0.8 above target at +2.8% for headline PCE (1 tick higher sequentially) and core PCE also +2.8% (1 tick lower sequentially) .

For those tracking calendar 2025 numbers under Trump vs. Biden’s last full month in office (Dec 2024), Trump’s headline PCE inflation is 1 ticks higher than Biden’s +2.6% while the Sept 2025 core PCE is 1 tick lower than Biden’s +2.9%.

In tracking the sequential MoM numbers for inflation signals, the Goods PCE price index has moved materially above recent months at +0.5% MoM vs. +0.1% in August and -0.1% in July. Nondurable Goods posted +0.7% MoM vs. +0.2% in Aug and -0.1% in July. So that signals upward price pressure in Goods.

Goods PCE inflation remains low on a YoY basis at +1.4% but keeps moving notably higher with each new month after being in deflation mode earlier in the year. As we have covered earlier, Energy Goods and Services were notably higher in Sept YoY at +2.7% and a YTD high – in contrast to Trump’s very vocal public statements to the contrary. Food is also higher at +2.4% in Sept and at a high in YTD 2025 (see Retail Gasoline Prices: Biblical Power to Control Global Commodities 11-13-25

Simplifying the Affordability Question 11-11-25)Meanwhile, Services PCE price inflation YoY is ticking slightly lower sequentially to +3.4% from +3.6% in August and more notably lower from earlier in the year with +3.8% in Feb 2025.

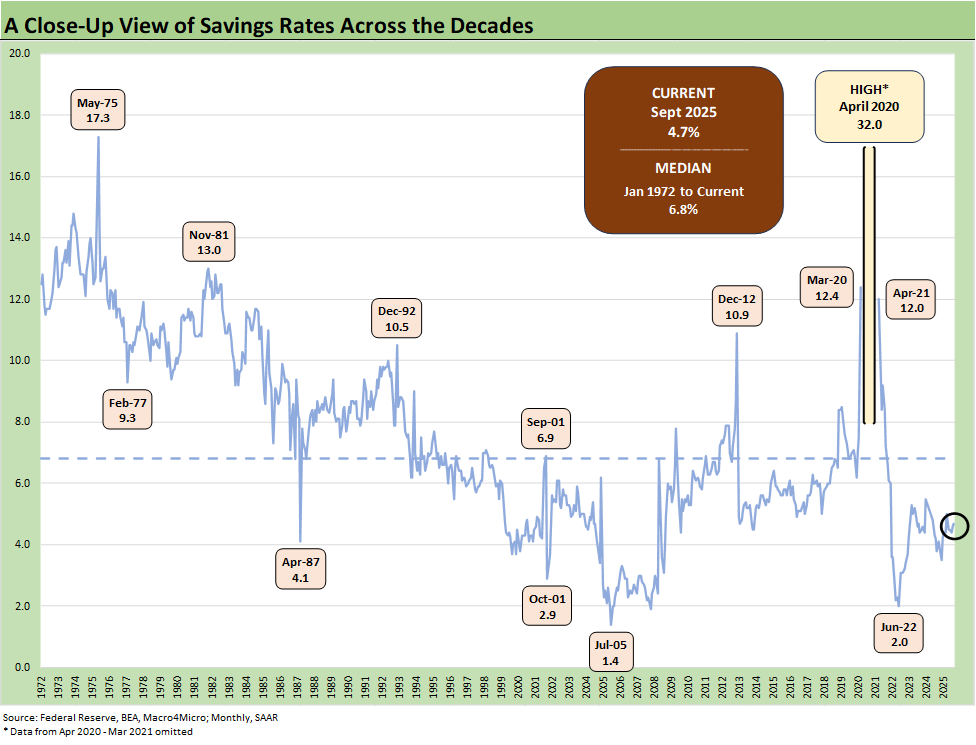

Savings rates are around YTD lows at +4.7% and flat sequentially to August even if down from a high of +5.7% in April. Real disposable income was +1.9% YoY and running below real personal consumption expenditure (PCE) levels of +2.1%. That real PCE level of +2.1% is a low for the year. Durable Goods PCE was down the most to +2.1% from 3.8% in August and highs of +8.6% in March and +7.8% in April.

Given the focus on FOMC policy vs. consumer pressure tied to affordability, we listen to the political noise on the subject to try to filter the spin down to a few basics:

Higher is not lower.

Sideways is not lower.

Higher is not always “high” in historical context.

“Flat” headline can have a lot of moving parts higher, lower and sideways.

There are a lot of line items that matter more to some than others.

Sequential MoM trends can sometimes be more important than YoY.

When we consider the level of tightening that could guard the system against a return to the stagflation of 1980-1982 or 1973-1975, the relationship of fed funds to PCE (or CPI) is critical in terms of the Fed mission. So, the fact that Trump originally wanted to cut fed funds by 300 bps (give or take) was not historically a “prudent” (sane?) statement coming off the highest inflation cycle since the 1980-1982 double dip.

The “Fed Funds minus Core PCE” differential since 1973 offers a read on “real fed funds” and to what extent the Fed is engaged in “real” tightening as opposed to the “closet accommodation” that we saw in much of 2H22 when tightening was moving into higher gear but badly lagging inflation. Trump is essentially calling for negative real fed funds.

The long-term differential of core PCE vs. fed funds is +1.5%, and the differential now is +1.1%. That still leaves room for easing, but the final judgement on actions comes down to how you see the tariff threats, the supply vs. demand side of the equation for goods, payroll economics in a world of mass deportation, household inflation expectations, and what that might mean for stagflation risk.

A glance back at the stagflation years of periods such as 1973 or 1981 and the various

“prevent defense” moves of the 1980s remind us how aggressive the Fed felt the need to be. The idea that Trump would put in a “Fed head” with negligible capital markets experience, a few short roles as a “professional appointee” and time served in conservative think tanks is too similar to what he had planned for the BLS. The stakes for the Fed are dramatically higher than for the BLS, which is bad enough (see Happiness is Doing Your Own Report Card 8-1-25)

Fed independence will not be dead – yet – given the voting structure and “relative” operational independence, but it will clearly be “mostly dead” (to quote Miracle Max).

Fed independence is not dead. Just mostly dead. Mostly dead is slightly alive. - Miracle Max

The forecasts for lower rates and more FOMC cuts in 2026 could soon become a political decision more than an economically justified move, but that is the drama for late spring 2026.

The above chart updates the long-term time series from 1972 for PCE vs. core PCE across the decades and cycles. We see the 2.6% headline PCE long-term median in the lower left (below the current 2.8%) and the 2.5% core PCE median (vs. current 2.8%). That is dramatically better than where we came from in 2022 but still well above the 2.0% target.

The Sept 2025 PCE numbers are at reasonable levels in long-term context, but they are in somewhat of a stall with numerous key lines going in the wrong direction. The SEP 2024 report and dot plot kept the PCE inflation forecast for 2025 unchanged from June at 3.0% headline and 3.1% core. We still have 3 months to go for reported numbers (Oct, Nov, Dec). It will be very interesting to see how the Fed SEP report and ensuing commentary address these forecasts during a period of very limited economic releases with the shutdown fallout.

The dot plot and forecasts in September were not dovish by any stretch (see FOMC: Curve Scenarios Take Wing, Steepen for Now 9-17-25) and were not materially different from the June meeting (see FOMC Day: PCE Outlook Negative, GDP Expectations Grim 6-18-25). The next set of Fed moves in Dec and Jan decisions come at a time when Trump attacks on macro statistics and independent agencies are nothing short of alarming.

The White House game plan has devolved to attacking the data when it is not supportive or having hired guns investigate the mortgages of select officials who are not on Team Trump. We have a lot of talking heads currying favor with the White House, and we don’t expect a fresh edition of “Profiles in Courage” any time soon.

The above chart frames the long-term differential history between PCE and core PCE since 1972. The long-term differential is zero and we are currently at zero. The volatility around that compressed long-term median ties into the energy wildcard with some food distortions also back in the 1970s. We look at some of the CPI energy and food inflation moves in separate commentaries (see Inflation: The Grocery Price Thing vs. Energy 12-16-24, Inflation Timelines: Cyclical Histories, Key CPI Buckets11-20-23). Food and inflation have been near the top of the affordability political rage-fest. The fact is both energy and food are higher in 2025 and again in the current PCE report.

The above chart looks at a shorter timeline from 1997 to offer a better visual scale separate from the wild 1970s and 1980s. Debate in financial and economic circles rage on around whether the target should be 2.5% or 3.0% or in some other range. The above chart offers a reminder of how hard it is to get to 2.0% or below for headline PCE or core PCE. The earlier chart covers the timeline from the inflationary/stagflationary periods of 1973 to 1982 to hammer that home.

The “1997 to 2025” period also shows a rare stretch at or below the 2.0% PCE line and core PCE median. It took a lot to go wrong in that time horizon to cross that 2.0% threshold. The events along the way included tech bubbles bursting in 2000-2001, oil crashes in the late 1990s and the late 2014 to early 2016 period, and a systemic bank system crisis from 2008 to 2011 (including sovereign stress) to get us there. The COVID pandemic was a new one for the modern capital markets.

In the above timeline, we even see deflation in the post-crisis recession trough in mid-2009. The collapse in oil prices in late 2015 and then the COVID impact in 2020 gave an assist to low PCE. Oil is a big headline mover whenever there is a sharp decline or spike, and we have had plenty of both.

It is interesting that the topic of the Feb 2022 invasion of Ukraine and ensuing oil and gas spike never seems to find a way into the Trump and MAGA rhetoric on inflation in 2022. That was a major factor in inflation, but the economic reality did not serve the domestic political priorities.

The Biden politics and stimulus definitely had a major inflationary impact on pricing and supply-demand imbalances after COVID. That is also the case with the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

Energy has been in deflation mode for part of 2025, and that helped dampen the inflation headline numbers. As 2025 wore on, energy inflation has gone the other way and notably in areas such as electricity and piped utility gas (see CPI September 2025: Headline Up, Core Down 10-24-25, Simplifying the Affordability Question 11-11-25, Retail Gasoline Prices: Biblical Power to Control Global Commodities 11-13-25).

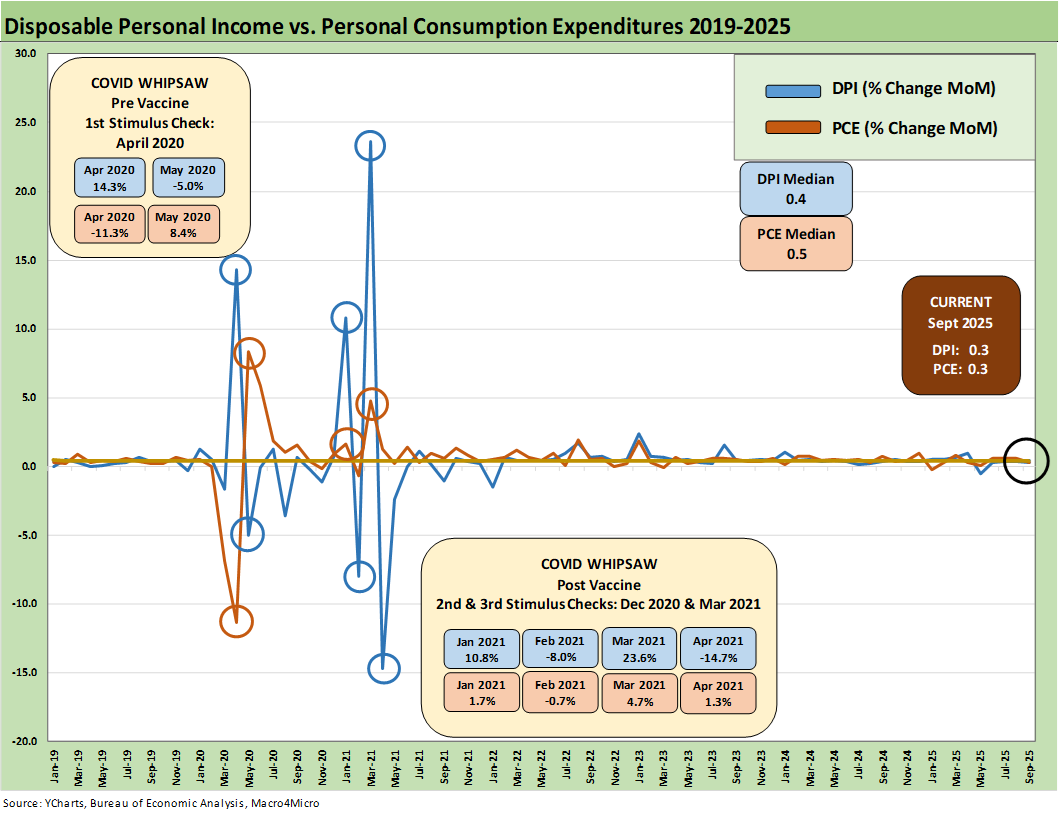

The above chart covers the time horizon for DPI vs. PCE from early 2022 as the tightening cycle kicked into gear after March 2022. Life in Jan 2022 was still quiet for Disposable Personal Income. We like to include this and the following chart just given the heavy mix of disinformation and politically axed story lines we constantly hear from Trump on Biden being the cause of all the macro problems at the end of 2025.

Accurate factual and conceptual frameworks of “the now” matter more than qualitative political spin looking backwards. That said, having a sense of what the numbers were then helps clear up the misinformation nonsense. After all, this is a very different world of tariffs and top-down government policy with very different tax structures and priorities.

The stimulus overload of 2021…

Looking back before the start of this chart, the 2021 period was a big macro rebound in GDP off the COVID peak period. The strong macro backdrop in 2021 and heavy dose of fiscal accommodation did not mesh well with residual supply-side shortages in goods broadly as 2022 saw the end of ZIRP and a material inflation spike.

Oil was a problem after the Putin invasion of Ukraine in late Feb 2022, and inflation hit a high in June 2022 at +9.1% for CPI as a headline grabber (headline PCE at +7.1% in June 2022) before the steady inflation slide to current rates. Core PCE had dueling peaks at +5.6% for Feb 2022 and Sept 2022.

The above chart plots MoM Disposable Personal Income vs. PCE and offers a read on how wild things got during and right after the pandemic peak. This is a chart we use each month to revisit the DPI swings that came with the three COVID relief/stimulus packages. That included two under Trump and one under Biden.

The COVID relief binge…

As a reminder, Trump signed the CARES Act in March 2020 (shows up in the DPI in April 2020) and Trump also signed the Dec 2020 legislation disbursed in Jan 2021 (Trump seldom mentioned that Dec 2020 one since it was easier to blame Biden and Powell). Biden signed the America Rescue Plan (disbursed in March 2021) that was a demand pile-on (we would argue over the-top-stimulus) in a supply-constrained environment (thus inflation). The DPI and PCE wave tied to each of those shows up in the chart above.

As a reminder, the vaccine was announced in early Nov 2020 just ahead of two stimulus actions. That was soon to be a factor in PCE patterns and lag effects. The quarterly GDP numbers in 2021 on the post-COVID bounce were numbers generally not seen since the Reagan and Clinton years (see Presidential GDP Dance Off: Clinton vs. Trump 7-27-24, Presidential GDP Dance Off: Reagan vs. Trump 7-27-24).

COVID was a distinct period for supply chains and supply-demand imbalances. With tariffs and potential trade wars, it will remain important to look for similar imbalances whether in narrow product categories or in broad commodities and materials areas. So far, the major trade partners have not initiated much in retaliation with the exception of a brief China spat. That has mitigated the damage but that de facto submission could comes back to haunt some major trade partners if others run for office with a “get tough” election pitch.

Jacking up aluminum, steel, copper on the materials side and seeking even more tariffs on lumber was not and is not a great idea for keeping prices and costs contained. Auto tariffs in Section 232 are extreme even after the array of “deals” and could go higher if the USMCA breaks down in 2026. We saw semis, pharma, and aircraft/engines/parts added to the Section 232 pipeline although most of the aircraft/parts risk was mitigated in EU talks. Recent period brought in commercial vehicles, branded pharma, cabinets, and a range of targets on national security grounds including upholstered furniture (making the world safe for “fat asses.”)

The above table plots the monthly Disposable Personal Income MoM change numbers vs. the Personal Consumption Expenditure MoM numbers across the years from 2019 through July 2025. It is an easy scan across key time periods for a look at turning points in DPI (e.g. stimulus payments) or PCE.

One exercise to do from time to time is to look at Table 1 in the monthly PCE release for the granular dollar amount on each line. The line items can sometimes show some volatility. We like to look for gaps between DPI and PCE and moves in Personal Savings.

Any reader of Table 1 can simply tick off which lines might come under pressure in coming months. Examples include expense lines such as Medicaid (post tax bill) or durable goods that face tariffs. It is always worth remembering that a tariff is a regressive tax that hits lower income consumers harder and the same for small businesses. The same is true in Medicaid costs based on the income brackets of Medicaid users. A loss of health care benefits and higher pharma costs is a zero-sum game with other consumption lines. The current ACA premium spikes will also be a zero sum “game” for many budgets.

The above chart updates the savings rate history with the latest number flat MoM at 4.7% after a 2025 peak in April of 5.7% (as revised). We have looked at the savings rate dynamics in earlier commentaries (see Savings Rates: Context Across the Cycles 10-27-23). Savings rates peak in times of worry (occasionally panic) as evident in the chart above. As of now, households are clearly spending even if some more come to regret it when credit card bills come due.

The period leading into May 1975 was no picnic after the massive stagflation bout and the same was true in Nov 1981. Dec 1992 had a raft of issues as the commercial real estate bubble was bursting (and hammering some banks), the leveraged finance boom was on the back end of the default cycle, the thrift crisis effects were still playing out across some major regional economies (notably TX and CA), and the regional oil patch pain that had come home to roost in 1987-1990 was lingering.

See also:

Credit Markets 12-1-25

Market Commentary: Asset Returns 11-30-25

Mini Market Lookback: Back into the June 2007 Zone 11-29-25

Durable Goods Sep 2025: Quiet Broadening of Core Capex 11-26-25

Retail Sales September 2025: Foot off the Gas 11-25-25

The Curve: Flying Blind? 11-24-25

Mini Market Lookback: FOMC Countdown 11-23-25

Employment Sept 2025: In Data We Trust 11-20-25

Payrolls Sep25: Into the Weeds 11-20-25

Mini Market Lookback: Tariff Policy Shift Tells an Obvious Story 11-15-25

Retail Gasoline Prices: Biblical Power to Control Global Commodities 11-13-25

Simplifying the Affordability Question 11-11-25

Mini Market Lookback: All that Glitters… 11-8-25

Mini Market Lookback: Not Quite Magnificent Week 11-1-25

Synchrony: Credit Card Bellwether 10-30-25

Existing Home Sales Sept 2025: Staying in a Tight Range 10-26-25

Mini Market Lookback: Absence of Bad News Reigns 10-25-25

CPI September 2025: Headline Up, Core Down 10-24-25

General Motors Update: Same Ride, Smooth Enough 10-23-25

Mini Market Lookback: Healthy Banks, Mixed Economy, Poor Governance 10-18-25

Mini Market Lookback: Event Risk Revisited 10-11-25

Credit Profile: General Motors and GM Financial 10-9-25

Mini Market Lookback: Chess? Checkers? Set the game table on fire? 10-4-25

JOLTS Aug 2025: Tough math when “total unemployed > job openings” 9-30-25

Mini Market Lookback: Market Compartmentalization, Political Chaos 9-27-25

PCE August 2025: Very Slow Fuse 9-26-25