Inflation: The Grocery Price Thing vs. Energy

We look back at food inflation as a reminder of why history matters. Except in politics. Groceries don’t deflate.

The economics team says I can promise food deflation…

The idea of lower grocery prices got some airtime this past week, so we update the history for the obvious point – things are not going back to the way they were for that special word “groceries.”

Politics is politics, but somewhere along the way some of the talking heads confused lower inflation with lower prices. The history of aggregate food CPI deflation is almost nonexistent even if inflation and price increase trends swing around.

Some individual food groups can deflate in a world governed by supply and demand, but overall prices reverting to the “good old days” is not something you see in the Food CPI time series.

The other political promise was lower oil prices, where the history of deflation is much more favorable even if it might be a challenge to get oil and gas companies to voluntarily blow up their own economics with excess production and supply excess. After all, unlike some in Washington, the E&P companies have mastered the concept of supply and demand.

The above chart plots Food CPI from 1972 to current times. The food inflation numbers swung around and notably so in the 1970s, but deflation (price declines) was extremely rare. When it occurred, it was minimal.

In other words, promising lower grocery prices on the campaign (with all the props to go with it) was not exactly rooted in economic reality or history. The admission by Trump this past week that lowering food prices would be “very hard” is certainly in line with history (!).

We use this chart above for All Food CPI, but we could just as easily break it down into Food at home and Food away from home. The latter brings a lot more into the cost equation (and thus the price) with labor, real estate costs, etc. Those factors only make deflation more challenging in the away from home category.

Lower food inflation overall (not lower prices in aggregate) makes sense unless we see major tariff distortions for certain product lines. If we see tariff battles break out, the subcategories will revert to supply and demand. Imported food products might see shortages to go with higher costs (“buyer pays” the tariff no matter what the new resident in the White House will keep saying), and those products facing tariff retaliation from Mexico, Canada, China, or the EU could see US supplies rise and bring price relief in select food groups. That sure will not help domestic farm interests.

The supply and demand relationship is part of it, but pricing power by branded food companies is a separate discussion. Large or multinational packaged food companies are typically not inclined to reduce prices out of the goodness of their hearts. Grocery stores have thin margins and need to pass cost increases on. Whether they will reduce prices when costs move lower is another topic.

The energy story is a radically different one than food. Energy costs also feed into the food price story given how energy costs can influence food costs (freight and logistics, gasoline surcharges, operational processing costs, packaging, etc.). The same is true with natural gas (fertilizer costs, etc.). We don’t expect Putin fans to blame him for any inflationary effects on “groceries.”

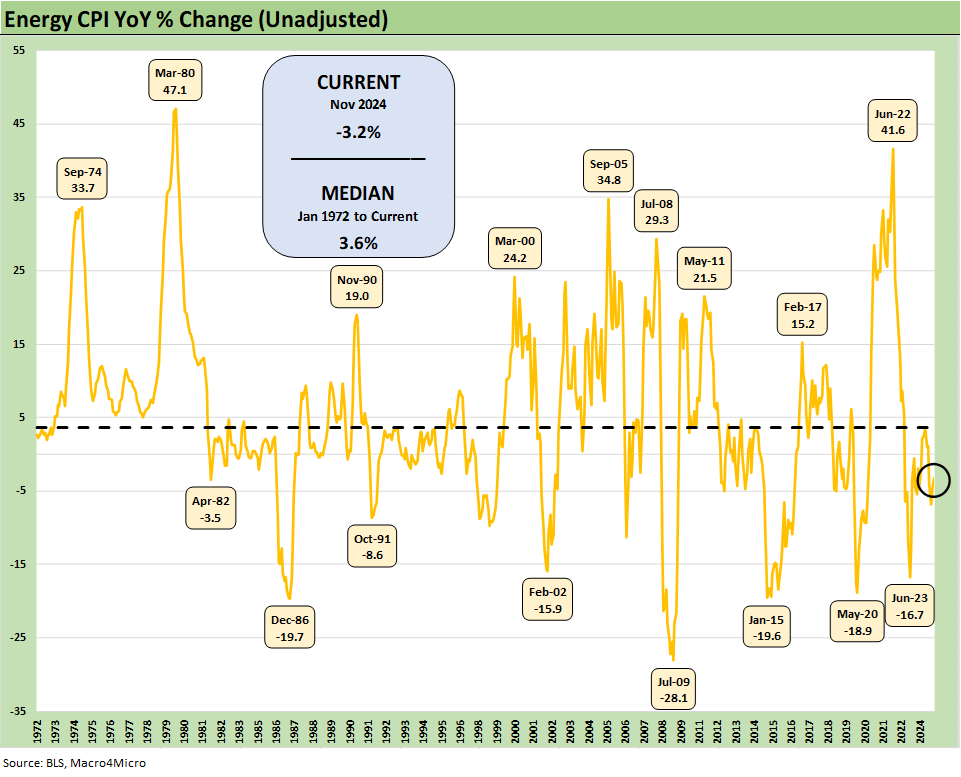

We include the above chart for Energy since this is more like what Trump promised for food (i.e. a big decline). As evident in the chart, you can get material deflation in energy and very pronounced spikes as well. The US markets are quite familiar with both. The oil spike to records in 2008 ahead of the late 2014 to 1Q16 crash was a reminder. So was COVID.

Those of us sitting in gas lines on odd-even license plate days (gasoline rationing) back after the Arab Oil Embargo of late 1973 rolled into an ugly 1974 stagflationary recession can attest to the inflation and deflation potential for energy. I covered the oils in the 1980s and the only thing everyone knew for sure was that oil prices were heading to $100. Of course they hit prices closer to $10 in the summer of 1986.

In the end, we are not sure how many actually believe that Trump could bring down food prices. We would assume at least the same folks who thought he won the 2020 election. Maybe he will have better luck with oil and gas since both will continue to post even more production records in 2025 as we have seen for a while now.

The wildcard in that oil price picture is Canadian oil and what happens with tariffs. If the US keeps Canadian oil flowing into the US and continues a planned move to export more light crudes and build out more infrastructure, that could even generate an OPEC (read Saudi) supply response like we saw in 2014. That would be a giant tax cut for the US consumer and help fuel lower inflation broadly on the indirect cost impacts. That would not do wonders for mass produced EV growth (and OEM profitability). It seems like that outcome would make Trump and many consumers happy.

See also:

Inflation Related:

CPI Nov 2024: Steady, Not Helpful 12-11-24

Payroll Nov 2024: So Much for the Depression 12-6-24

Trade: Oct 2024 Flows, Tariff Countdown 12-5-24

JOLTS Oct 2024: Strong Starting Point for New Team in Job Openings 12-3-24

PCE Inflation Oct 2024: Personal Income & Outlays 11-27-24

Mexico: Tariffs as the Economic Alamo 11-26-24

Tariff: Target Updates – Canada 11-26-24

CPI Oct 2024: Calm Before the Confusion 11-13-24

The Inflation Explanation: The Easiest Answer 11-8-24

Payroll Oct 2024: Noise vs. Notes 11-2-24

PCE Inflation Sept 2024: Personal Income and Outlays 10-31-24

JOLTS Sept 2024: Solid but Lower, Signals for Payroll Day? 10-29-24

Tariffs: The EU Meets the New World…Again…Maybe 10-29-24

Trump, Trade, and Tariffs: Northern Exposure, Canada Risk 10-25-24

Trump at Economic Club of Chicago: Thoughts on Autos 10-17-24

CPI Sept 2024: Warm Blooded, Not Hot 10-10-24

Inflation Timelines: Cyclical Histories, Key CPI Buckets11-20-23