Trump, Trade, and Tariffs: Northern Exposure, Canada Risk

Canada is the #1 export nation for the US. We look at the risks as Trump threatens immediate action on USMCA (NAFTA) even before the 2026 review.

Don’t be a tariff hoser to Canada. We ARE worthy.

With the Election Day deadline closing fast and some massive economic policy differences in play for trade and tariffs, we look at the US-Canada trade risk factors and the moving parts of the import and export mix following our earlier review for Mexico (see Trump at Economic Club of Chicago: Thoughts on Autos 10-17-24).

The battle with Canada in 2018 seemed to turn on a few simple but sometimes intractable items (e.g. dairy, cheese, forest products, etc.) and the battle for the upper Midwest votes (notably Wisconsin) loomed large. If Trump reopens discussions on too many food products right away in 2025 (rather than the official negotiated mid-2026 review date), the path will get treacherous quickly for the legacy NAFTA deal as revised into USMCA under Trump back in 2018 (effective 2020).

Canada remains the #1 exporting nation for the US ahead of Mexico but with a more favorable mix of US export line items to Canada that could be used as retaliation targets if the process unravels. The contractual agreement in the USMCA calls for a midyear 2026 review for all parties, but any of the parties can separately terminate with 6 months’ notice. The review process is distinct from the rights to exit the deal with potential recurring annual reviews after July 1, 2026.

The more likely source of extreme tension will be Mexico and not Canada given the overlap with the mass deportation requirements set by Trump and Miller et al. Trump has promised to “tariff” countries that do not fully cooperate with the deportations.

The above chart plots the timeline for imports from Canada and exports from the US to Canada. The pattern of the import-export lines tracks closely. Where we see notable divergences, those are generally more a function of oil prices. Crude oil is by far the #1 import into the US by Canada and amounts to more than double the #2 Canadian import, which is Autos/Light Duty Vehicles.

With Canada a major supplier of natural resources (metals/mining, energy, forest products, etc.) the “coming and going” have been a benefit to the US and especially as Canada moved toward high rates of investment that also benefited the high end of US exports (autos, aerospace, commercial vehicles, capital goods, technology related, pharma, etc.). We look at that export mix later in this commentary.

In the context of a trade clash and high tariffs, the US export list to Canada constitutes the “retaliation target list,” and they would most certainly retaliate if provoked.

In this piece, we look at some of the import-export product categories that will be worth considering if we do in fact roll into a blanket tariff battle with Canada that sees the USMCA terminated in 2025 as Trump gets fired up for a tariff frenzy. He can run with his tariff plan without interference from viable Congressional action. Technically, Congress could take action, but the Senate and House GOP failed to act last time and just had a lot of noisy hearings.

Since Trump’s first term, the Senate and House Committee heads in the GOP are now little more than a boned fish parade. Senators who pushed back are gone (e.g. Corker, Toomey), and other Senators got the message (go along or meet a similar fate). Advisors who opposed the actions (think Gary Cohn) did not make it past 2018. Nothing from a theoretical Democrat-controlled House could get past a GOP Senate anyway whether by outright majority or filibuster. Trump would veto it anyway. Trump ignored Congress in his first term and would again – only with greater ease.

The “Supremes” have demonstrated a user-friendly profile for Trump to say the least (life among the Christofascist forum), so legal challenges are unlikely to go anywhere. You never know with “the Robes” but Trump looks to have free reign. Based on his blank check from the Supreme Court for “official duties,” Trump could always shoot a few committee heads.

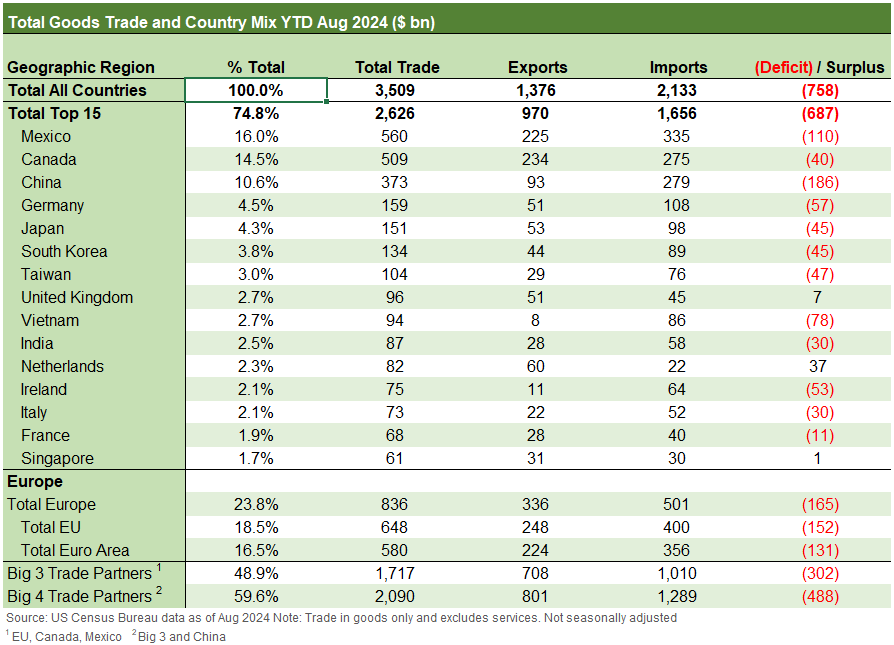

The above table shows the 2023 full year numbers for the top trade partners. “Total trade” is defined simply as “imports + exports” but we also show the export and import and include the trade deficit. The next chart just updates the above for the YTD 2024 numbers.

At this point, Trump has abandoned all economic theories on what trade deficits mean and erased the concept of comparative advantage and low-cost sourcing from his memory (if it was there to be erased in the first place). Then again, his Bibles were made in China, so it must still be in part of his memory when he is seeking to maximize his profits. We can assume that makes low-cost sourcing “Blessed and Godly” in some cases. (Sourcing a Bible from an officially atheist state is not without its ironies.)

Total trade is important since it should be read as “economic activity” across a wide range of services and goods sectors that get touched when that import crosses the border. Freight and logistics (rail, motor carriers, warehousing), banking, insurance, retail and all the employee paychecks that come with that add to the array of benefits in both directions. Toss in a higher tax base at the state and local level and the multiplier effects from there and the value of thinking “simply” about trade deficits soon becomes the problem of “thinking wrong.”

At the very least, there were lessons to be learned from the first experience (besides that the “buyer pays” and not the country of export, which is a fact not learned by Trump).

Trump made a declarative statement yesterday in a social media post that the “abusing country” pays the tariff (e.g. China) and not the buyer. The buyer pays is a fact – not an opinion. How that upfront tariff will get filtered through the cost of sales and pricing chain is where economic opinions come into play. Trump is asking his supporters to deny facts and suspend reality. This is hardly the first time.

The above chart updates the trade stats for the YTD metrics, which overall keep the upper rankings in place. We see Europe or the EU at #1 in total trade followed by Mexico at #2, Canada at #3, and China at #4 for a total of the Big 4 at just under 60% of total trade.

From what we heard in the recent Bloomberg interview (see Trump at Economic Club of Chicago: Thoughts on Autos 10-17-24), Trump seems to be set to do battle with all of the Big 4. He also took swipes at South Korea even though he renegotiated/revised a free trade deal with them in his one term (the original “KORUS” was set up under Obama in 2012). Trump’s team also set up a Free Trade Agreement with Japan that was effective as of the start of 2020 before COVID.

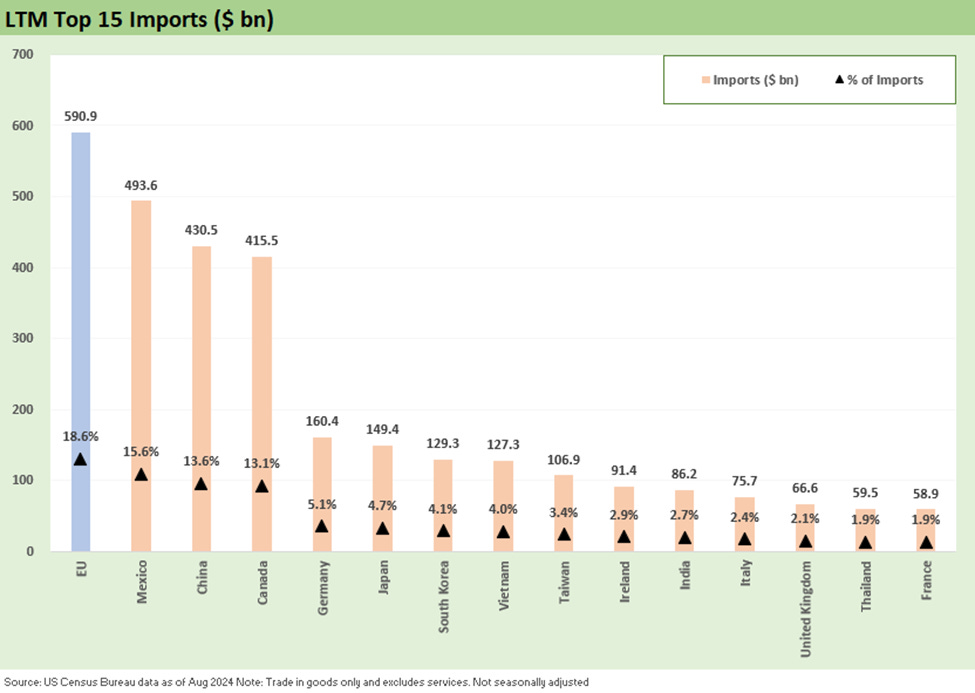

The above chart ranks imports only rather than total trade, and we see the EU at #1 in total and Mexico at #2 overall. Mexico ranks at #1 for imports when ranked by nation with China at #2 by nation and Canada #3. The exposure by nation drops off sharply from there with spots #4 through #6 seeing major automotive trading partners with substantial transplant activities in the US (Germany, Japan, South Korea).

The auto transplant activities have attracted massive investment in the US (mostly red states) including from US suppliers as well as offshore suppliers from the home country who often set up shop in the US through subsidiaries or joint ventures. That often leads to material import flows of high value-added components (e.g. engines) and more imports from Mexico to those transplant operations.

The growth in the US markets have drawn very high interest from franchise auto dealers with the non-US brands doing very well in dealer portfolios (see Credit Crib Note: Lithia Motors (LAD) 9-3-24, Credit Crib Note: AutoNation (AN) 6-17-24). Auto retail and finance is a major industry, and the auto retail sector employs more people than auto manufacturing. Auto sales, parts and repair, and finance and insurance continue the theme of how such supplier-to-OEM chains keep the economic activity and GDP growth going with an expanding population of drivers.

Even with all the economic multiplier effects, Trump had some strange things to say on the growth of the auto manufacturing presence in the US by European, Japanese, and South Korean auto assembly:

“Assembly, like in South Carolina. But they build everything in Germany, and then they assemble it here…They get away with murder because they say, ‘Oh, yes. We're building cars.’ They don't build cars. They take them out of a box, and they assemble them. We could have our child do it.”

Besides a display of possibly incurable ignorance of the auto manufacturing sector after all this time since the start of his first term, that statement also insults and understates the critical importance of assembly line work in assuring quality. It also ignores the massive capex and construction spending that goes into the assembly plans and related suppliers from the US and offshore that often operate nearby or get additional business from current operations. There’s also a constant stream of retooling across model years and product changeovers.

Trump’s simplistic statement ignores all the related industries that feed these mini-ecosystems and employ tens of thousands of people and support local service businesses. The comments also miss the importance of efficiency of the assembly operations in minimizing unit costs to support financial health and earnings of the OEM operations (that also has allowed workers to get paid more).

The world of global supplier chains has been upon us for years since Toyota revolutionized high volume auto manufacturing. A great book on the topic is The Machine that Changed the World, which is a must-read to understand how the industry got here. We assume this book or related readings did not get much conversation or “eye share” around the Trump policy planning team.

We can point back at the embarrassment of Trump’s effort in his first term to come up with a Section 232 rationalization for auto tariffs. The effort was such a failure to support auto tariffs that the report was not publicly disclosed and then actually withheld from the public despite Congress demanding its release (see Trade Flows 2023: Trade Partners, Imports/Exports, and Deficits in a Troubled World 2-10-24). The reason given below can be translated as “It was too embarrassing to allow public release and would have been shredded by anyone with a remote clue.”

“The President may direct the Secretary of Commerce not to publish a confidential report to the President under Section 232 of the Trade Expansion Act of 1962, notwithstanding a recently enacted statute requiring publication within 30 days, because the report falls within the scope of executive privilege and its disclosure would risk impairing ongoing diplomatic efforts to address a national-security threat and would risk interfering with executive branch deliberations over what additional actions, if any, may be necessary to address the threat.”

That is how embarrassing it was and was a poor reflection on the trade and tariff SWAT team.

Trying to unwind decades of getting these supplier-to-OEM chains in place (note: Supplier Tier 1, 2, and 3) is not a frictionless wheel. The financial toll of trying to eliminate trade deficits through exorbitant tariffs will not be a fender bender (think Demolition Derby for the auto sector). Industry players and securities owners should be concerned.

We are already seeing worsening labor tension at some companies such as Stellantis around shifting capex plans. In response, the UAW is seeking the equivalent of the pre-crisis Jobs Bank to come back. Stellantis is already seeing threats of work stoppages. When conditions change expectations, conflict rises.

The trade press has been covering the rising concerns around the election and deferral of capital budget planning commitments until after the election. We can assume that election certification will take time even with the votes in as litigation and election denial flares up and the courts get busy from states to the Federal level and perhaps a trip to the Supreme Court again. Even just the fear of volatile policy action is driving delays.

Imagine a formal decision on broad tariffs. Will the tailpipe emissions rules get scrapped under Trump? What will that mean for budgets and capacity planning in EVs? Will tax credits change? We keep seeing the questions popping up, and companies need to plan with risky inputs or stall. Which supplier chains in which countries will be most affected? Mexico? China? Canada? The EU?

Even contractual commitments create more risk in the supplier to OEM process. Tapping the brakes is where economic growth fades as we saw in capex in 2018-2019 trends. The Fed noted as much during their 2019 easing.

The above chart plots the trade deficit with Canada across time. We see the impact of the oil price crash from 2015 to 2020 and the effects of many oil sands operations coming on line across these years as oil rebounded in 2021 and then spiked with Russia-Ukraine in 2022.

When we get into the line items further below, we will also see high levels of refined petroleum products and crude oil from the US into Canada. Set against the backdrop of record oil exports by the US and record US production of crude oil and natural gas, the export-import flows get confusing around why we import so much oil from Canada. It is a story for another day, but it is about costs and grades of crude and where the US sellers can most profitably deploy their output.

Canada is also a complex story around where their massive reserve and production base can be sold. Oil sands have some access to “tidewater” via the West Coast, but pipelines into the East of Canada are absent (and blocked). That means the US is the main event for land-locked Alberta.

It is going to be interesting to see how Trump approaches Canadian crudes in his blanket tariff game plan. You never know. He likes to trade from often irrational and self-destructive positions.

The combined power of the US and Canada in energy creates a lot of opportunity for the US producers to optimize their mix of crude, NGLs, LNG and refined products across the US market, the regional markets (Canada and Mexico), and global markets (Europe and Asia). Cooperation with Canada could be better for global security than a trade battle involving oil. That gets back to the Trump-Putin (and now Musk) relationship questions. That will be a topic for post-election assessment and how Russian oil will be treated in the supply forecast.

After Russia invaded Ukraine, the opportunities for exports grew in leaps and bounds and this is where the “drill, drill, drill” crowd and the climate crisis groups get to wage their wars. The rigidity of views will keep the barriers high to optimizing a US national plan on hydrocarbons output to reach the right numbers (domestic use, export of oil, NGLs, LNG and natural gas by pipelines across borders, e.g., to Mexico).

The above chart updates the import history from Canada across the years. As discussed in the prior chart, the swings in recent years are often simply tied to the price of oil in 2022 and imports also reflecting the steady growth of oil sands production volumes. The volume of oil would be higher if not for the takeaway capacity constraints.

We see the earlier spikes in oil prices back in 2004 to 2008 after the Iraq War escalation created some dislocations. Oil hit a high in the summer of 2008. Then the shale and unconventional drilling boom took over the supply story ahead of the Saudi price war in late 2014 into 2016. During COVID, oil prices were slaughtered with negative WTI futures at one point and a barrel of heavy Canadian crude costing less than a pint of Molson.

Trump historically has been favorable on pipeline construction to move Canadian crudes South (Keystone, etc.), but the complexities of the two-way round-trip traffic in autos is mirrored (in less complicated fashion) in the mixed flow of crude and refined products from the US to Canada.

The hatred of pipelines we often see in US political debates is mirrored to the east of Alberta in Canada (notably Quebec) with BC in the West more mixed on the topic but also not friendly to Alberta’s needs. That is a separate story for another time.

Canada is a G7 nation with a highly developed economy and is not a major trade partner as a source of labor arbitrage. That makes it a very different set of trade conditions between the US and Canada relative to the Mexico dynamics.

The low-cost wage structures in Mexico can be crafted politically as offshoring jobs to minimal wage and benefit plants (“race to bottom”). The hostility that colors the Mexican relationship thus gets more political support to attack the migration of so many assembly line and manufacturing jobs across many industries but most notably along the auto production chain right through to finished vehicles rather than just suppliers.

The US has a very high value-added mix of export products as detailed below. Trump kept complaining about Canadian deficits, but the US had a surplus ex-crude and Trump was pushing for Keystone. It is safe to say that Trump is unencumbered by logic and rhetorical consistency.

The chart above on imports and the chart below on exports highlights the two-way traffic in vehicles and auto components that would make a falling out with Canada on trade so damaging if it turned into a USMCA exit on blanket tariffs. The imports from Canada are extensive as the #1 importer, and the role of heavy Canadian crudes that dominate the rankings are much desired feedstocks for the higher tech refineries (notably in the Gulf) who have the capacity and made the billions in investment to process such crudes. The economics of the WTI-WCS differentials are often very attractive, and such feedstocks also generate more product streams from advanced refineries.

Logic would imply that Trump has been poorly advised by voicing an apparent ambition for trade conflict or some form of unconditional surrender by trade partners. Of course, in his first term he used national security trade laws against Canada even though they are in the NORAD chain of command in a nuclear age where missile technology is proliferating. Canada supports US security (they are the “good guys” in contrast to Russia). Canada was also a founding member of NATO, but NATO is a Trump target and is a separate snake pit of issues ahead.

In terms of the Section 232 laws used last time, those were largely modified under Biden with EU allies after the NAFTA-to-USMCA process. Could Section 232 come back? Trump did not make the world safe for lower cost cans by his actions since the US generally has high-cost aluminum and Canada low cost with very efficient mills and low-cost power (electricity is a major part of the aluminum production cost structure). That is why so many US companies had major operations in Canada before global consolidation changed the ownership structures globally.

On a side note, declaring Canada as a national security threat ignores the history of military action by Canada in the same wars on the US side. Canadian soldiers were the stuff of legend in some critical battles in WWI (think Passchendaele). Canadians fought alongside the US in WWII and Korea. No “losers” or “suckers” in that group. Trump will need to have some rationale to slap tariffs on Canada and will likely violate numerous WTO rules to do what he is seeking to do.

The above chart is something we have looked at in past commentaries, and the main point is that US exports to Canada cut across some critical product groups that are higher end product categories than what we see with Mexico. Trading with Canada is trading with a valuable buyer of manufactured products (autos, aerospace, trucks, pharma) as well as commodities (energy, metals, agriculture/food, inorganic chemicals, petrochemicals/plastics).

A trade clash with Canada would hurt many industries and lead to some weakness in exports and corporate capex since capacity planning cannot be evaluated with certainty. Analysis of the economics of capex needs reliable input and not unreliable, erratic policies emanating from the White House. These conditions prevent sound investment decision-making by those evaluating the long-term asset planning for capex and project analysis.

The effects of much less aggressive tariffs than what Trump is proposing does not take speculation on how it will end. We have 2018-2019 to look at. 2018 was a market mess and 2019 brought fed easing on weak exports (in part on retaliation) and weak capex on policy uncertainty and the ability to take a “wait and see” approach.

Trump and his allies will not even admit what happened in 2018-2019. They just call it the “greatest economy in the history of the world” and an “economic miracle.” The only miracle is that they have been able to sell that false reality. Others on the top import list that could be swept up in tariff issues include Taiwan just behind Vietnam. We also see India and Thailand on the top importers list.

The layers of analysis in pricing and volume forecasts and how various trade partners will react (retaliation, etc.) will be too uncertain for many. The result? Less economic activity. See the hot stove? You put your hand and on it in 2018-2019 during the imaginary greatest economy in history (see HY Pain: A 2018 Lookback to Ponder 8-3-24, Histories: Asset Return Journey from 2016 to 2023 1-21-24). This time, we recommend that you don’t turn all the burners up and put your face on it.

As the import list above shows, higher tariffs (Trump was discussing the need for 50% in recent comments rather than 20%) will bring even worse results. Why? Because the planned tariffs are higher and broader and more antagonistic (grounds for retaliation). Manufacturing concerns that are more insulated from the tariff effects can get defensive and use pricing power on the lack of import supply. They don’t have to expand capacity. That impulse is for profit maximization.

Meanwhile, manufacturers that see their supplier chain costs rise will be worse off financially. They are not going to suddenly vertically integrate in a time of uncertainty and unit cost pressure. They will more likely than not retrench.

The rising raw material prices in metals and mining and fabricated products will see prices raised – like they did last time. The fact that supply chains were derailed as well is a circumstance that gets overlooked in the discussions. What will happen in a trade clash with the 4 largest trade partners? Or do we throw in Vietnam as well with the other top import nations above?

In the above chart we get into the Autos and Transportation imports from Canada followed in the next chart by the Exports of such products from the US to Canada. We do not have the data on what share of specific models moved across the border in each direction, but the relative flows and mix of vehicles vs. components are clear enough. It is a very busy supplier-to-OEM chain. Disrupt it and you can be assured economic activity will be lower – as in less busy.

Slowing down an auto sector that was getting hammered in the COVID supplier chain crisis and semiconductor shortages and was at recession volumes as recently as 2022 is not a good idea. The Trump plan looks like a replay with higher tariffs and a more onerous set of reactions in economic activity. The line items are there to look at.

We reviewed the production by OEM and models up in Canada as we did in the earlier Mexico commentary. We looked at the production by model of the 5 major operators including Toyota at #1, Honda at #2, GM at #3, Stellantis slightly behind it at #4, and Ford a more distant #5. Through 9 months YTD 2024, the total production of those 5 totaled around 1.02 million in Canada.

With Mexico production and its larger more diverse group of operators almost 3x that total in Canada (Source: Automotive News), Mexico is still the bigger risk than Canada for autos. They are both in USMCA, so the uncertainty overlaps. If Mexican production gets disrupted, the market will need the Canadian production. That means auto prices (new and used) will soar again on supply-demand imbalances. There is also the question of the supplier chain needs of Canada and the US for Mexican-made parts. Once again, inflation risk lurks on supply issues and unit cost pressures on tariffs flowing through.

In the case of light vehicle production in Canada, Toyota and Honda have taken the lead over the legacy Detroit 3 players in production (former Chrysler assets in Stellantis). Honda makes the CR-V and the Civic in Canada while Toyota assembles the RAV4 and RX. GM makes the Silverado, Chrysler makes the Pacifica and Voyager, and Ford makes the Edge.

The above chart shows a very active production chain and cross-border activity with Canadian produced “light trucks” running around 5x car production volumes through 9 months. We see more vehicles coming into the US from Canada than going the other way given the breadth of products built in the US and narrower range in Canada. Canada gets diversity from the US exports, but they have some plants building vehicles in some of the most popular US vehicles and product segments.

Aerospace has significant production in the US and in Canada and some suppliers in Mexico for business jets. The US is a major supplier of aerospace products to Canada including Boeing, Airbus, a range of other jets, rotorcraft, and suppliers. Canada is home to Bombardier, who sold its C-Series operations to Airbus as the industry now has production of the A220 in both Canada and Alabama.

All in, the US and Canada have a very busy relationship across the border encompassing the full range of products from high value-added manufactured products all the way down to a range of commodities, with energy and autos being the two largest groups. Why roil that flow of products with a highly disruptive tariff program that is destined to result in major economic damage?

Contributors:

Glenn Reynolds, CFA glenn@macro4micro.com

Kevin Chun, CFA kevin@macro4micro.com

See also:

Trump at Economic Club of Chicago: Thoughts on Autos 10-17-24

Tariffs: Questions that Won’t Get Asked by Debate Moderators 9-10-24

Facts Matter: China Syndrome on Trade 9-10-24

Trade Flows: More Clarity Needed to Handicap Major Trade Risks 6-12-24

Trade Flows 2023: Trade Partners, Imports/Exports, and Deficits in a Troubled World 2-10-24

Trade Flows: Deficits, Tariffs, and China Risk 10-11-23