How Do You Like Your landing? Hard or Soft? Part 2

We review PCE and fixed investment lines for the quarters around the recession periods back to the 1973-1975 stagflation.

We take a walk down memory “alley” (it is too dark and spooky to be a lane) for a reminder of how many things need to go seriously wrong to bring a hard landing in 2023.

While the current backdrop does have high inflation and rising rates, the US starting point of extremely low unemployment, a strong competitive position in many industries, a healthy bank system, and favorable trend lines in YoY inflation comps is a good starting point.

The PCE line rules the growth numbers. While the most vulnerable investment lines are Structures and Residential, there is still room to maneuver.

In this commentary, we follow up the “hard landing vs. soft landing” topic that we started in Part 1 (see How Do You Like your Landing? Hard or Soft? Part 1). Here, we focus on a lookback across the cycles with an emphasis on high visibility line items that drive GDP growth. We do this by breaking out the BEA line items that we like to watch – Personal Consumption Expenditures (PCE), Gross Private Domestic Investment (GPDI) and related components – across multiple cycles starting at 1973. Then, for a deeper analysis of each cycle, we look at eight quarter increments including those leading into or bracketing recessions. The eight quarter increment is adequate since the longest recession during this 50 year period was less than five quarters.

Our aim in this exercise is to provide historical context on not only “how bad it can get”, but also “how much it takes” to drive a material contraction. Across the timeline, we see systemic financial system stress, war, radical structural change in the economy, exogenous shocks, reckless and excess credit, low quality underwriting, high inflation, and geopolitical fallout. There is something for everyone across the time horizon.

Our goal for the charts is as follows:

Highlight the big movers of past cycles: We always hammer home that it is hard to have a recession with positive PCE. As we discuss, we had one soft landing recession that did not even hit negative PCE, but it takes a subjective Business Cycle Dating Committee (no matter how much objective data they invoke) to get there. Unemployment is very low in historical context and PCE has ticked higher for three straight quarters in 2022, so it will take a lot to go wrong from here.

Underscore how much pain it will take for a hard landing: As we will break out, the hard landings of past cycles came with brutally negative GPDI and a few quarters of negative PCE. In the 2008-2009 stretch, PCE was negative for 5 of 6 quarters. In the post-TMT recession of 2001, there were no negative PCE quarters.

Frame the scale of moves across economic subsectors: We want to give some context to the relative magnitude of the contractions across key line items such as PCE (over 68% of GDP) and the various GPDI lines (Nonresidential Structures, Equipment, Intellectual Property, and Residential). The collective GPDI lines comprise around 18% of GDP with Government consumption around 17% before we get into the effects of items like Inventories and Net Exports (i.e., trade deficits, which lower GDP).

Reinforce that GDP growth and market volatility (equity and bond booms and busts) can be quite different: The irony of the 2001 downturn was that it saw the mildest recession in the postwar era in terms of GDP but saw the longest HY default cycle (longest, NOT highest) and brought events like Enron and WorldCom and waves of legislative and regulatory overhaul. Market bubbles do not necessarily pile on economic downturns.

Onward march of recessions…

The chart collection further below goes all the way back to the 1973-1975 recession that saw the Arab Oil Embargo on the way to what became the longest post-war recession at the time (16 months). That recession was later tied in duration by the 1981-1982 downturn (16 months) before being eclipsed by the post-credit crisis recession that ran from the Dec 2007 peak to the June 2009 trough (18 months).

We include both legs of the 1980-1982 double dip in the mix of charts and include the short first leg from the January 1980 peak to the July 1980 trough. The stagflation period recessions and credit crisis of 2008-2009 were all “hard landings” but each had their own distinctive causes, symptoms, and economic metrics profiles.

We also look at the 1990-1991 recession that wrapped up a wild ride in the 1980s. We include the 2001 recession that flowed out of the then-longest expansion in history (120 months) from the March 1991 trough to the March 2001 cyclical peak. The expansion from the June 2009 trough was yet another record-long expansion than ran past the 10-year mark before crashing into COVID at the Feb 2020 peak.

Recent history has included some very long expansions but in periods of relatively low inflation. The inflation X-factor entering 2023 adds a material risk not seen since the early 1980s and that complicates the longer expansion theories that say “it is too early for a downturn” since the COVID recession.

A lookback at Personal Consumption and Private Investment lines across the cycles…

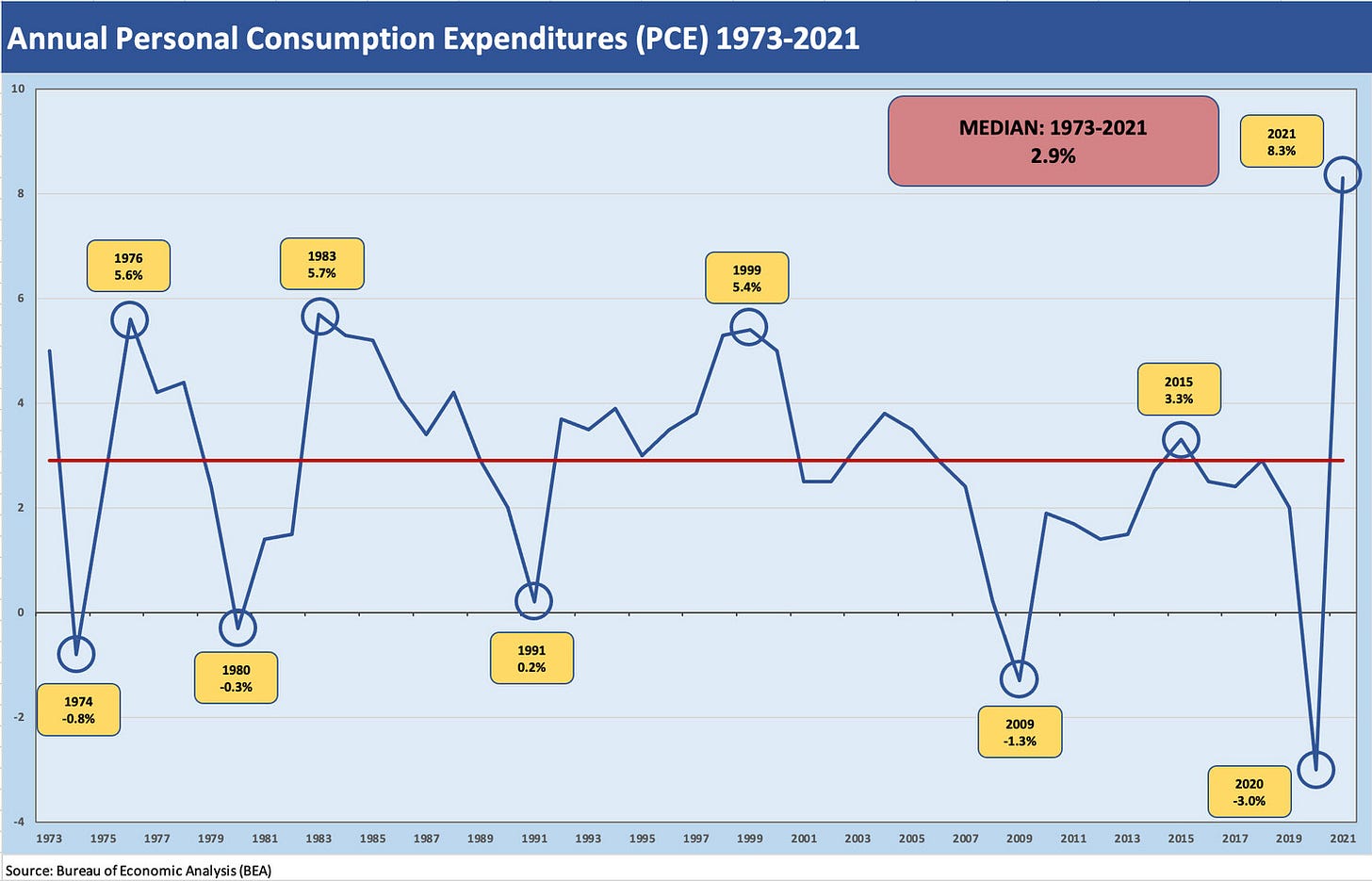

The charts below plot annual PCE growth and GPDI growth from 1973 to 2021. In a separate table, we examine the quarterly numbers for 2022 through the third quarter. We discussed recent quarterly GDP trends in Part 1 of this series, as well as in an earlier commentary (see 3Q22 GDP: It’s the Big Little Things).

We present this line chart for annual PCE to highlight the tighter Ho-Lo range vs. other GDP growth lines. That comes with the caveat that this line is an overriding variable with respect to its share of GDP (typically 68% to 70% area). PCE often drives the planning of investment (GPDI) or hiring by goods and services providers to meet demand, so PCE is very much intertwined with critical line items such as homebuilding, auto manufacturing, and a wide range of real estate asset classes.

The PCE time series above frames some highs and lows across the cycles and details a median of just under 2.9%. The annual PCE low points across the long term timeline are muted vs. the 2% handle GDP growth numbers typically seen. At -3.0%, COVID is the notable exception. The -1.3% after the credit crisis underscores the resilience of the PCE line driven by a growing population. The COVID pandemic stands alone in scale for its PCE impact - negative and positive. Such a deep cut turned around to generate the highest PCE on the chart in 2021. Distortions created by especially ugly downturns also give rise to outliers on the upside.

PCE does not tell us the story of where household or corporate sector balance sheets are positioned at a point in time. The market was reminded of the importance of balance sheet health when weak household and corporate balance sheets were a major driver of the worst recession on our list: 2008-2009. Weak balance sheets also lead to a credit contraction - the household balance sheet fallout made for an especially brutal downturn. In contrast, relatively healthy balance sheets in 2022 should help mitigate potential hard landing risks in 2023.

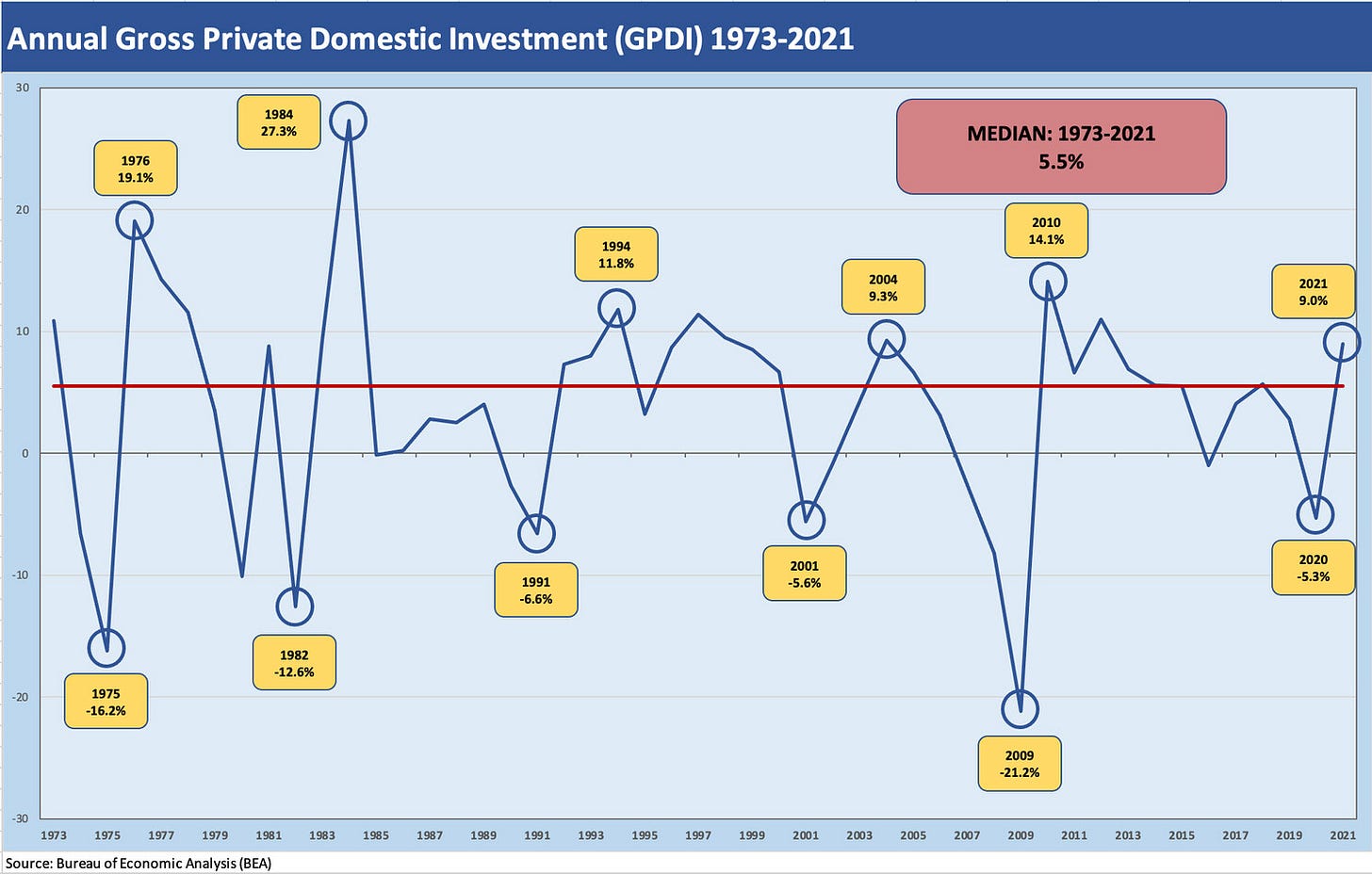

The above chart plots the annual rate of growth in Gross Private Domestic Investment (GPDI). The time series makes clear that this metric moves in a far wider range than PCE. We see the big bounces coming out of downturns such as the rebound from 1982 to 1984 and from 1975 to 1976. After the stagflationary swings of the earlier cycles, the moves from High to Low were more muted until the implosion after the credit crisis where construction industries were reeled in, housing entered a multiyear crisis, auto companies filed bankruptcy, and OEMs took a lot of suppliers with them.

Major credit contraction is the worst ingredient to add into a steep demand downturn for risky assets that comes with a spike in defaults. At such times, refinancing opportunities are badly impaired. With the crisis, the world of ZIRP arrived and that allowed a slow and sustained recovery into the early years of the longest cyclical recovery in the postwar era at over 10 years.

The 2% handle average annual GDP of the Obama and Trump years saw 12 years without getting north of a 2% handle annual GDP growth rate. Then GDP took a sudden move lower with COVID. However, GPDI put up a strong rebound year in 2021 ahead of the weakness that came in 2022, which saw two materially negative quarters as detailed in the chart collection below.

The GPDI line is where a big part of the story will get told in 2023. The weight of Fed hikes and inflation takes time to roll through the system and for layoffs to take effect on planning by producers of goods and services. The GPDI line is where 4Q22 earnings season might help give some directional clues on which sectors will be increasing or decreasing across Structures (e.g., investment in construction, additions to properties in health care, commercial, and industrial, etc., plus E&P drilling outlays), Equipment (e.g., capital goods, auto/truck/freight, non-defense aircraft, etc.,) and Intellectual Property (e.g., software, tech design and related services, arts and entertainment, etc.). On a side note, I don’t envy economists charged with forecasting all of that by rolling it up from the trenches and framing in BEA measurement context.

THE PRIOR RECESSION TIMELINES BY QUARTERLY GDP LINES...

A note on the data source: For the charts below covering the GDP, PCE, and GPDI by quarter, we use the BEA data from their Interactive Data service. The data is basically the main contents of the GDP release Table 1 (Real Gross Domestic Product: Percent Change from Preceding Period). See the BEA source for the details, but the data reflects myriad restatements and measurement policy changes over the decades. I spot checked some vs. past press releases and could see some changes. For this purpose, the main point is that the charts use the same data source for all the recessions and periods detailed in each chart below. It is the BEA’s bat and ball, so the source is consistent with their methodologies.

We roll the charts out below in reverse chronological order starting with the trailing eight quarters through 3Q22 and ending with the 1973-1975 recession period. We break the 1980-1982 double dip recessions into two charts for a total of eight tables.

_______________________________________________

4Q20 to 3Q22: NO RECESSION...YET

We will start with a copy of the latest trailing eight quarters. We covered 2022 in detail in Part 1, but we include this as reference here so you can compare and contrast as you scan the historical recession tables below.

A few highlights for the 2021-2022 period:

PCE lines are positive: PCE has ticked up for three straight quarters after falling from a banner post-vaccine 2021 set of numbers. Within PCE, we see Goods demand flagging but Services are holding in well. Job openings and low layoff rates are expected to move in an adverse trend line into 2023, but that is not what we saw this past month (see Jobs and the Fed: JOLTS Gets Heavy Powell Focus, Jobs Conundrum: Good is Bad, Bad is Good).

GPDI is sliding and should get worse in 4Q22: There is a major decline underway in Residential, but the single family and multifamily houses under construction are keeping economic activity high as starts and permits decline (see Market Menagerie: Home Starts – Will Housing Starts Infect Multifamily). The market has posted 6 straight quarters of contraction in Structures and 6 straight quarters of negative numbers in Residential alongside it.

GPDI and Structures: Real Estate and REIT outlooks will get a lot of attention in earnings season and the same for capex E&P (which flows into the Structures lines). E&P outlays are on every radar screen for obvious reason (oil and gas supply inflation, etc.), but the nuances across expanding investment in commercial real estate has a cloud over it heading into 2023. The Office Properties subsector has generated more worries around retrenchment in both investment (valuation trends) and credit availability (see Risk Trends: The Neurotic’s Checklist).

GPDI and Equipment capex trends: The Equipment line has been a good news item in 2022. This will be a source of focus for both the cycle and for any hints of changes in supplier chains as tension heats up in global trade (China) and companies keep revisiting reshoring some high value part of the supplier activity (e.g., chips). Reshoring vs. nearshoring/friendshoring will flow into US accounts in different ways. Capex budgets in manufacturing, energy, and TMT will be among the big-ticket items to watch. Defense spending will stay busy, and the Aerospace & Defense has a very long supplier chain in the US. Energy transition is drawing a large base of capex for energy, autos, power, and cap goods.

_______________________________________________

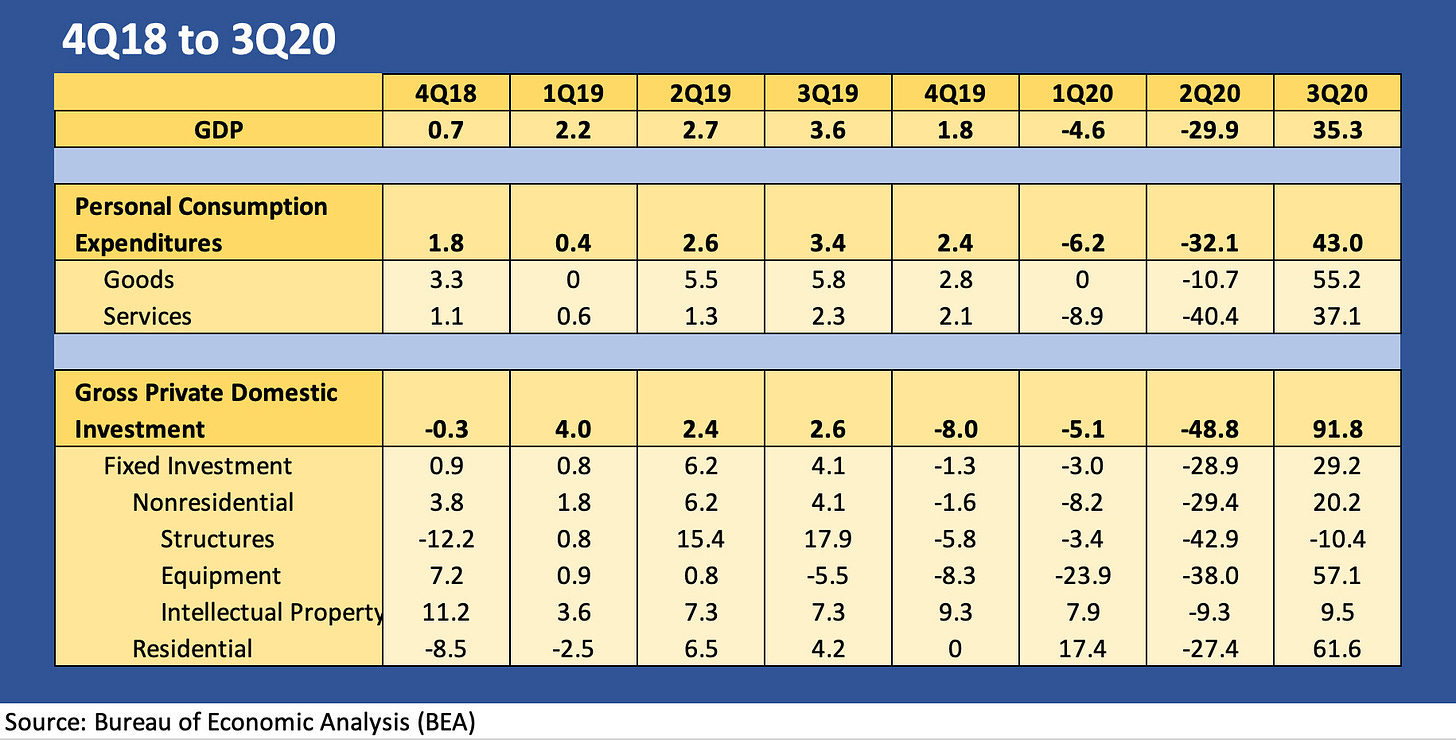

4Q18 to 3Q20: THE ROAD TO COVID AND LATE 2019 SLOWDOWN

The chart below frames the period from the sharp capital markets sell-off of 4Q18 and the mini-crash in oil on across the challenging year of 2019 and then into the COVID shock and 2-month recession of March 2020-April 2020.

The slide in 2Q20 GDP was other worldly, and the swings in payroll were numbers never seen for a plunge and ensuing rally in employment. The rise in unemployment rate from 4.4% in March to 14.7% in April 2020 and down to 6.7% by year end will not be duplicated (we hope). The early November 2020 news around a vaccine flipped the script into an almost indiscriminate rally in capital markets (the vaccine news hit the markets on Nov 9, 2020). The market was supported at sea level by a +35% rise in GDP in 3Q20.

GPDI dropped by almost 49% in 2Q20. Panic from the consumer sector to the manufacturing chain was rampant. Offices emptied out, lease defaults loomed, and mortgage defaults needed government intervention. It seems like an old story now, but the ability to spin dire scenarios and domino effects was not hard. The fiscal support combined with a very activist Fed-UST tag team (Powell-Mnuchin) arguably kept the credit market wide open and restored confidence quickly for a massive refi and extension wave in mortgages and corporate debt.

The timeline raises some interesting “What if?” scenarios around where the cycle was headed pre-COVID with “What if COVID did not happen?” guesswork. During 2019, the macro picture was fading and the yield curve was inverting later in the year. The UST curve was especially inverted in the 3M-5Y segment in Sept 2019 (see UST Slope Update: Some New Inversion Highs, UST Curves: Slope Matters, The Cash Question: 3M-5Y Yield and Slope).

In 4Q19, we see GDP slowing with GPDI at -8.0%. In 2019 and into early 2020, I had a view that the cycle had legs to push through the economic softening, but COVID cut those legs off a few weeks later. The reason I raise 2019 is that the threat of trade tension and tariffs undercut private sector investment in 2019, and the tension level could be much more acute in 2023 if China-US geopolitics go the wrong way. That is in the tail risk bucket that could keep nerves high on global capacity planning in the new year as China noise picks up.

_______________________________________________

4Q07 to 3Q09: THE HARDEST LANDING IN THE TIMELINE

We break out the details on the credit crisis recession period in the chart below. The downturn ended up as the longest one in the post-Great Depression era at 18 months from the Dec 2007 peak to the June 2009 trough. The chart begins in the quarter of the 2007 peak and ends in the first quarter of the next expansion (3Q09). We see 5 of 6 quarters from 1Q08 to 2Q09 post negative GDP.

The numbers are ugly, and the hard landing label is certainly merited. The -8.5% 4Q08 GDP line is only rivaled by the -8.0% of 2Q80 detailed further below as stagflation reared its head. 2Q80 saw a 22% Misery Index (inflation + unemployment) and came in the month (June 1980) that I got off the Amtrak train in aromatic Penn Station from Boston to start my first “real job.” The 22% was the all-time high. The 4Q08/1Q09 tandem in GDP was worse than the 2Q80/3Q80 combination.

The old economic principle is that credit expansion drives growth and too much credit drives bubbles. The other part of that is that old rule is that credit contraction drives recessions and minimal credit can cause a depression. This boom-to-bust and counterparty-heavy credit crisis never came close to the conventional definition of depression, which some frame as -10% for a year (i.e., annual GDP contraction).

The 2008-2009 period did earn the tag of the Great Recession given the near systemic collapse of the US and global bank system. While the financial system today looks nothing like the bank and brokerage system of 2008, there is plenty of room for asset quality problems and rising default rates overall. The healthier profile of the consumer sector today, a stronger bank system, and a superior regulatory overlay offer critical differences between 2008 and the end of 2022.

The importance of the PCE line is evident in this brutal period of late 2008 and early 2009. PCE was negative in 5 of 6 quarters from 1Q08 to 2Q09 with only 2Q08 cracking into positive at 1.1%. Looking across the GDP buckets, we see Residential had been in a swoon after the housing market peaked in late 2005. Since 3Q05, Residential was in negative territory for 15 straight quarters. Equipment went into double-digit negatives for 4 quarters with the 4Q08/1Q09 meltdown in 30% handle contractions. We see the Equipment line as a major differentiator in 2023 that will help the softer landing scenario and create a more 2001-like outcome for growth. That said, there are scenarios that can change that (China, Russia).

Structures strikes us as a wildcard in 2023 given the move in the yield curve and the rapid expansion in so many real estate sectors prior to COVID and some in the post-COVID period. Office Properties have been the headline clay pigeon of late, but the rate of building in a range of industrial sectors could call for a pause in the action. The E&P expansion programs that might unfold and energy transition investments should be supportive in 2023 in mitigating some of the downside.

The bottom line on the 2007-2009 period was that unemployment soared and lagged the recovery, credit was tight, and confidence was low. Housing was in a depression for a few more years. The energy sector was just getting started on its multiyear expansion that would unfold in the shale boom and bring waves of midstream expansion.

In contrast, the situation in 2023 will be very different. First and foremost, the bank system is much healthier. Home equity has soared even if getting scaled back by rising rates. In energy, climate politics clash with the need for E&P and related infrastructure. This battle will need to play out with a newly split Washington. More green lights on midstream would help. Geopolitics is also weighing on the direction of hydrocarbon exports and related infrastructure needs to supply export markets (e.g., pipelines). Basically, Europe needs energy help. In other areas, a return or relocation of supplier chains would also require more investment beyond Equipment.

_______________________________________________

4Q00 to 3Q02: SOFTEST LANDING ONE COULD HOPE FOR

The TMT bubble and an almost maniacally bad underwriting cycle led to the most protracted HY bond default cycle, even if it was not the highest default rate peak in history. The default rates rose sharply higher in late 1999 (despite a record NASDAQ run) and then got worse after the NASDAQ peaked in early 2000. Defaults and spread waves saw a double dip effect in late 2001 and again the summer of 2002.

Tech equities and debt-fueled Telecom and Media capex in the credit markets made for a wild experience in a post-bubble collapse. The equity and credit market implosions were not mirrored in the “real world” economy as evidenced in these numbers and in the attached chart. Greenspan nonetheless ran wild in easing and arguably set the stage for the later housing and structured credit crisis. We already discussed those policy actions in a separate commentary (see Greenspan’s Last Hurrah: His Wild Finish Before the Crisis).

We saw two minor GDP contractions across this period as noted above in the BEA data, but we did not see any PCE lines in the red. This period had seen a gross overextension in telecom and media capex fueled by debt. The market also saw massive capex expansion in the power sector. That excess then boomeranged after the meltdown. Commercial real estate saw retrenchment as the borrower victims of the period needed a lot less space. Many retrenched or filed bankruptcy and set off some space rationalization. That flowed into steep declines in Structures, but Equipment declines were quite manageable. Residential held in much better in an economy that had not yet seen the excess that would hit later when a flood of housing investment and lending was driven by Fed policies.

In terms of the capital markets excess of this TMT bubble period and comparisons to today, the current market in 2022 has seen plenty of excess but less in markets where debt-fueled capex was the rule. Today’s market had plenty of bad investments to make, but debt excess on the low end of the HY market has not been the norm as it was in the TMT bubble years.

_______________________________________________

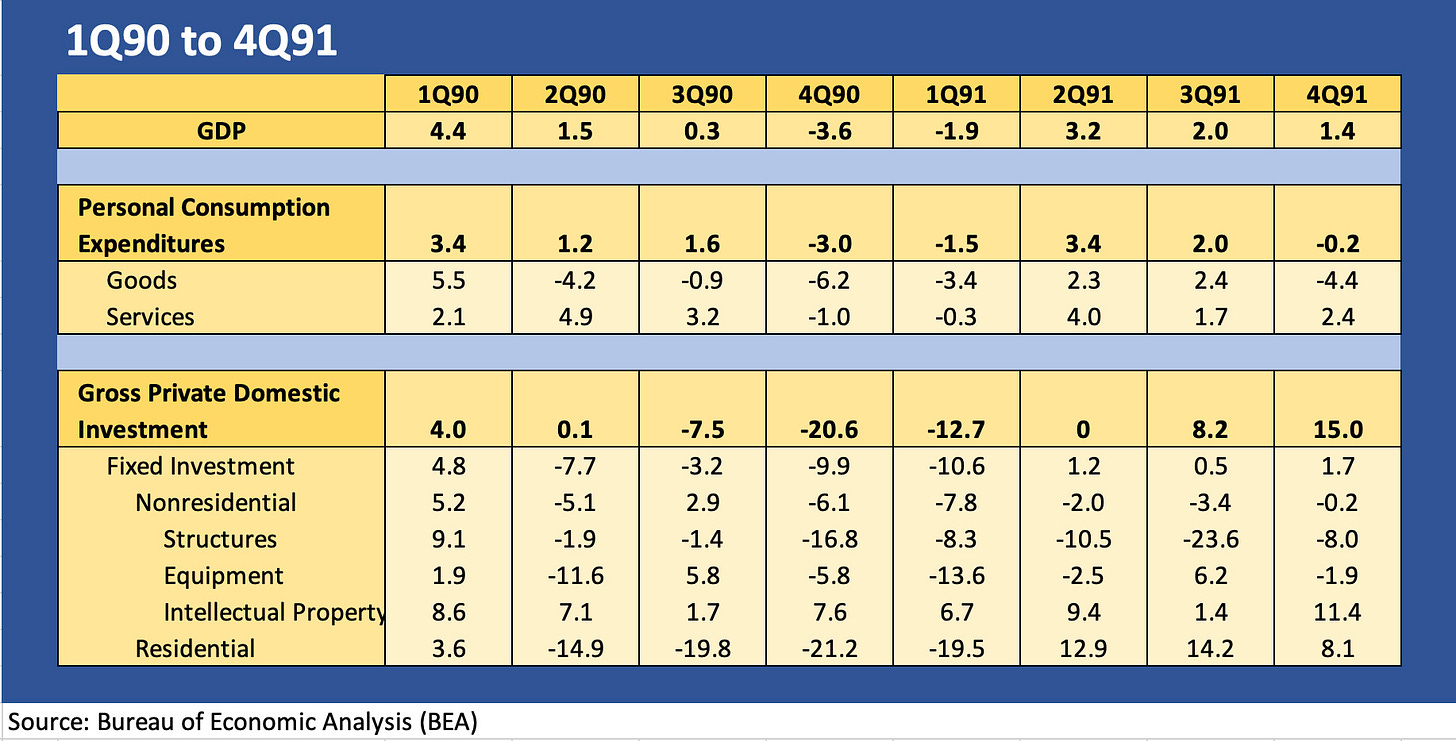

1Q90 to 4Q91: THE FIRST POST-LEVERAGE DOWNTURN

The late 1980s started to see a rapid erosion in the financial system and regional economies after what was a record rate of growth that included a doubling of the nominal GDP. The 1980s was a very exciting and sometimes turbulent period that saw the equity markets and the role of debt soar in relative terms. The public corporate bond market and an emerging HY bond market was born as deregulation brought rapid growth in sources of capital (e.g., mutual funds) and record assets under management that Wall Street was happy to find product for.

As we cite earlier, Econ 101 says credit brings expansion and too much credit brings bubbles or troubles. The 1980s drives that home that excess credit bring trouble when cycles start to turn down. During the 1980s, systemic corporate leverage broke sharply from the trend line. That set the stage for a market where orderly markets could not be made as risk tolerance faded. The low quality underwriting outstripped the depth of the secondary market and its ability to take blows in a downturn. The experience would get repetitive stress syndrome in later cycles. The pace of the excess was starting to blow up in 1989 as we cover in earlier commentaries (see Greenspan’s First Cyclical Ride: 1987-1992, UST Curve History: Credit Cycle Peaks).

The direction of the GDP line items over this narrow time frame shows the effects on the economy as much softer than what came before (the 1980-1982 double dip) but harder than what came after (the post-TMT soft landing of 2001). Greenspan was at the helm for both the 1990-1991 upheaval and 2001 experience. Greenspan responded with extreme easing to both downturns.

We see two negative PCE contractions in 4Q90 and 1Q91 quarters (during the Gulf War scare, the spike in oil, and as cascading problems peaked in the financial system). The contraction in Structures was material and painful and came with a national scale commercial real estate correction that hit many banks hard including a number of major regionals that failed.

Residential saw a brief but painful adjustment period that revisited some regional problems that had flared up in 1988-1989 as the oil patch crisis (notably 1987-1988) and an extended S&L meltdown weighed on both housing values and credit availability. The financial system stress peaked in 1989-1990 including bailouts at brokers such as Lehman and First Boston with Drexel filing Chapter 11. Some remnants of bank stress remained in place during the expansion with notable problems at Citibank, among others. The financial system stress added up to less credit in the system and a spike in defaults.

Again, this is not comparable to today in a market with highly regulated bank holding companies. Major brokers dependent on commercial paper access is now a relic of the past.

_______________________________________________

2Q81 to 1Q83: THE SECOND LEG OF THE STAGFLATION DOUBLE DIP

The second leg of the 1980-1982 double dip was the longer of the two earlier 1980s recessions. The first one in 1980 was in the Carter Administration and the second one came under Reagan in 1981-1982. The recession ran from the July 1981 mini-peak through the Nov 1982 trough. The downturn lasted 16 months and tied the Nov 1973 to March 1975 downturn for the longest downturn since the Great Depression. The post-crisis recession ending in June 2009 later broke the postwar (WW II) record at 18 months. We start the time series below in 2Q81.

Both legs of the double dip are dominated by the spike in oil prices, soaring inflation, and the extremely aggressive inflation fighting policies of Volcker after he took the helm in August 1979. We cover those policies in other commentaries, but his policy was to closely control monetary aggregates while letting fed funds float at levels that were usually (not always) well in excess of inflation (see Fed Funds – CPI Differentials: Reversion Time?, Fed Funds vs. PCE Index: What is Normal?). A high real fed funds rate was the order of the day and looked to succeed where the 1973-1975 policies fell short.

The high rates, high oil prices, and high unemployment made the Misery Index a popular metric (see Misery Index: The Tracks of My Fears). The toll those factors took were evident in four quarters of negative GDP during the span from 2Q81 to 3Q82 with one more quarter in 4Q82 rounding to zero. Per the BEA data, PCE held up better in the second leg of the double dip than the first, but GPDI was crushed in the second leg as the Structures and Equipment lines took a pounding along with Residential. The negative GPDI line in 6 quarters from 2Q81 to 4Q82 makes a statement with 4 of those negative quarters in double digits.

The timeline from 1979 to 1982 included a lot of deregulation and structural changes across industries even as household stress and corporate pressures were high and impaired the demand side. In looking back to the “then vs. now” equation, US industry was in a bad place in those days with Japan taking market share in Autos, Cap Goods, and Machinery and Equipment. Inefficiencies and high costs were a major problem in many industries, and the Aerospace and Defense sector was long overdue for a bigger role in the budgets that were unfolding under Reagan. Post-Vietnam syndrome gave way to the Cold War defense buildup of the 1980s.

Airlines faced deregulation in the late 1970s and into the early 1980s and fare wars and airline bankruptcies were widespread. The final death blow for many came in the next downturn in the 1990 recession. In autos, transplant capacity was just an early concept with Honda, who started building cars in the US in 1982. The view of labor costs and labor relations had been, if anything, a deterrent to foreign companies investing in the US. That changed dramatically into the 1990s and after as did the relative position of numerous US manufacturers in global competitiveness. The scale of the US auto sector in the US across a diverse range of OEMs is another positive difference heading into a period that may be a recession.

_______________________________________________

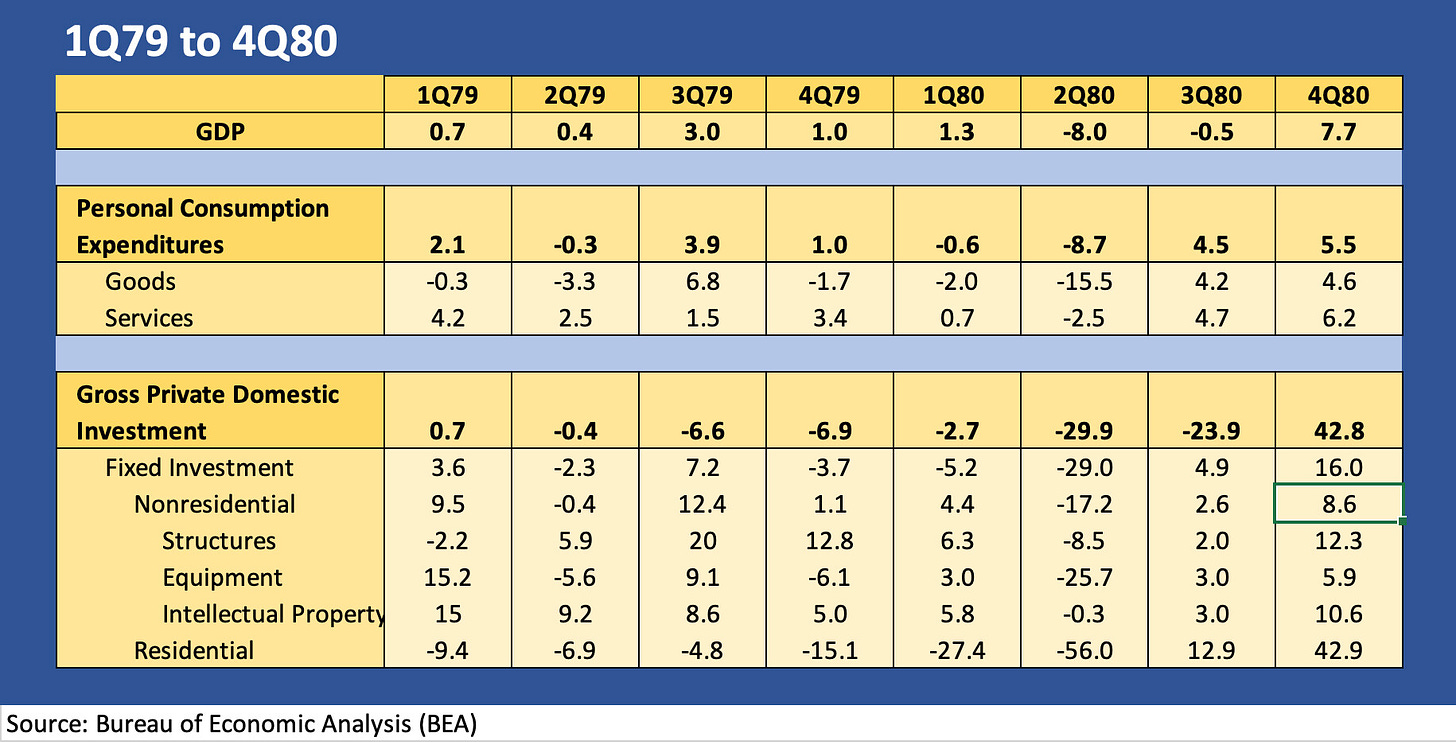

1Q79 to 4Q80: THE ARRIVAL OF INFLATION AND VOLCKER

The chart below looks at the first leg of the double dip recession from Jan 1980 to the July 1980 recession trough. The stagflation themes are very much in evidence today as they were in 1979-1982, but the confidence factor in oil and gas resources is night and day. Investing with confidence is critical and today’s businesses do not have to worry about running out of oil and natural gas any time soon. That is especially the case when comparing vs. the 4Q73/1Q74 Arab oil Embargo, but it was also a factor in 1979.

The 1980s would soon bring energy relief with production from the North Sea, Mexico, and Alaska into 1980. However, major new non-OPEC supplies had not yet arrived in force as of 1979. As a result, the Iranian Oil Crisis fueled more inflation and more supply fears. The oil price pain and fear of natural gas shortages all had an adverse impact on consumers and producers alike.

We see three negative PCE quarters from 2Q79 to 2Q80 with the recession months from the Jan 1980 peak to the July 1980 recession trough, including the market posting back-to-back negative PCE quarters during the 6-month recession. In GPDI, we see an ugly 2Q80 and 3Q80, but the numbers were recovering by the end of 1980. As we now know, the trouble returned, and the Fed tightened the vice again in late 1980s and in early 1981. Volcker kept the heat on, and that made the second leg worse in unemployment with contraction in manufacturing, construction, and housing. The Residential line was especially beaten down at the Misery Index peak. The 10% handle unemployment rates by late 1982 did the trick and brought inflation under control. The cycle turned.

Volcker was intent on staying the course and not repeating the policies of the earlier bouts of inflation, but it came at a cost to labor and the private sector. That dilemma is again the case today on rates vs. jobs and investment, and the market anxiety over rates and the shape of the curve at year end is signaling expectations of what many see as overdoing tightening. Those who worry about “underdoing it” are concerned that failure to kill inflation now could lead to revisiting of inflation in 2024 and a worse recession.

_______________________________________________

2Q73 to 1Q75: ARAB OIL EMBARGO, HIGH INFLATION, CONSUMER BEATDOWN

The chart below frames the 16-month recession from Nov 1973 to March 1975. The early 1970s was an especially crazy time in US history in terms of the pace of change in the economy, regulatory backdrop, and in policy decision-making in the US. From the tail end of the Vietnam experience to such events as Nixon going off the gold standard (Bretton Woods), facing the Arab Oil Embargo (4Q73/1Q74), dealing with Watergate (and Nixon resignation), the timeline was overwhelming. Framing the various stages of wage and price controls makes your head spin when it comes to drawing parallels (see Inflation: Events ‘R’ Us Timeline).

Among the takeaways from the early to mid-1970s was that wage and price controls do not work. Pent-up demand and supply-demand imbalances rule in the end. The market just got a fresh reminder in the supplier chain shocks.

Gasoline rationing can cause a very low level of confidence among consumers, and that also can infect the willingness to consume. The weak PCE numbers detailed in this time frame above offer some evidence. The 1Q74 period saw plenty of odd-even license plate days to get gasoline just to go to work. Meanwhile, inflation broadly and higher interest rates weighed heavily on households. Food inflation was also extremely high in 1973 (~20%) and 1974 (~12%). Retail prices for gasoline rose by over 20% in 1973 and 1974. Fuel oil was up by over 46% in 1973 and 30% in 1974. The majority of domestic crude oil was price controlled or the effects would have been worse. The Arab Oil Embargo weighed heavily but was ended in March 1974.

The breadth of adverse economic impacts really struck in 3Q74 to 1Q75. The end of the recession came with an especially brutal set of numbers in 1Q75 GPDI. Residential posted negative double-digit numbers in all eight quarters presented. We see four of eight quarters presented posting negative PCE. I recall from prior lives (I covered the integrated steels on the buyside in the early 1980s) that 1973 was one of the last great US steelmaking peaks in volume with solid profitability before that industry soon headed into a multi-year nightmare for the integrated steelmakers after this recession.

From beginning to end, the 1970s was a time of pain and change for many manufacturing industries from aerospace in the early 1970s (e.g., the Lockheed bailout and Boeing downsizing) to a shifting competitive landscape with Japan who was ascendant into the 1980s in autos, steel and machinery and equipment.

The 1973-1975 recession offers a lot of lessons from the fallout of inflation even if the structure of the economy was radically different and the financial system and regulatory overlay bear little resemblance to today. Inflexible policy making and an erratic political backdrop may be a similarity. The early 70s recession offers a reminder that supply and demand rules in all markets. Price controls temporarily put off the inevitable.