UST Curve History: Credit Cycle Peaks

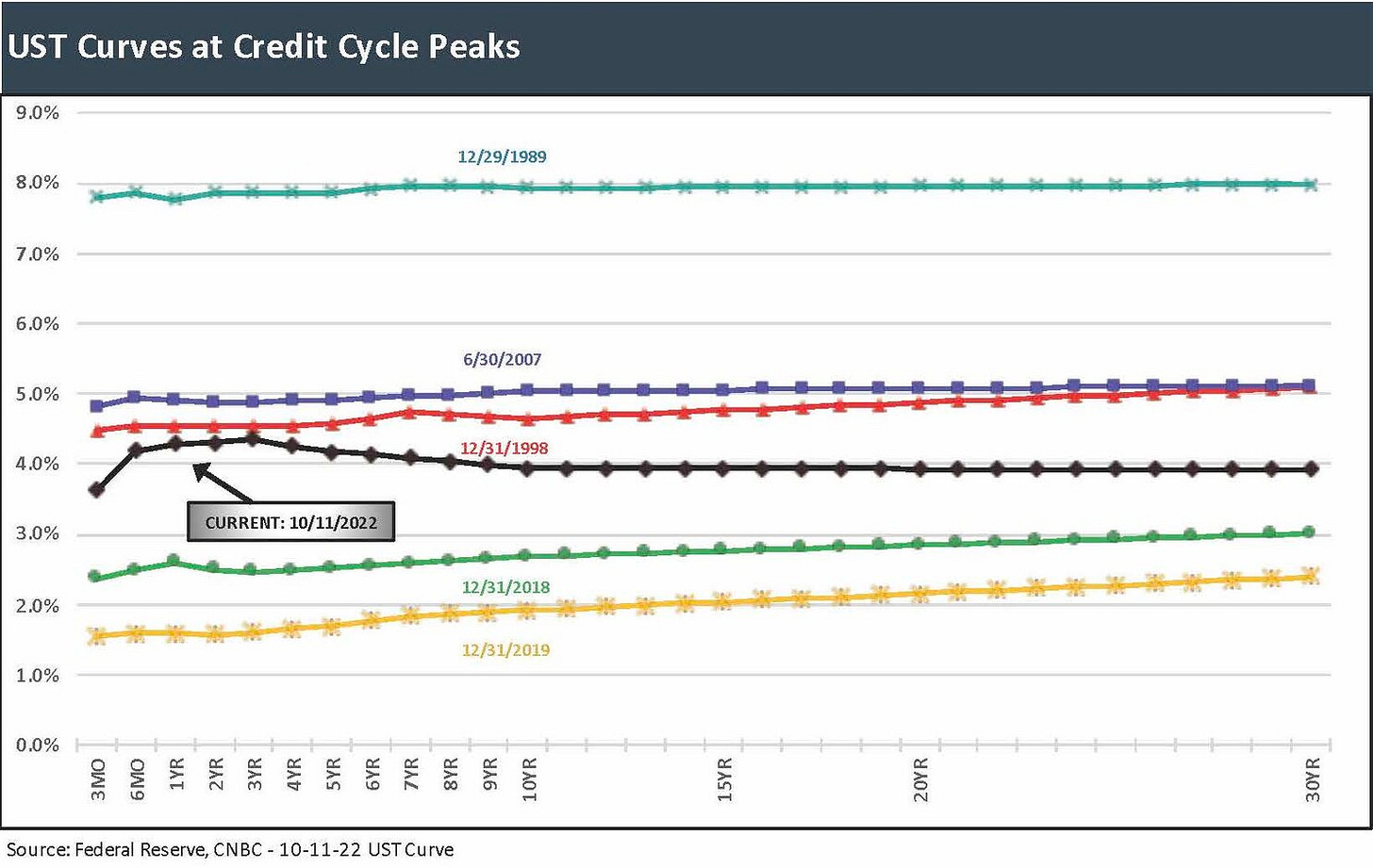

We plot the UST curves at “credit cycle peaks” as opposed to business cycle peaks. They are not the same.

As part of the lookback commentaries for historical context, this note reviews the UST curves for the time horizons we see as “credit cycle” peaks (as opposed to “business cycles” laid out by NBER).

I chose 1989, 1999, and 2007 with COVID ending the debate on recession in 2020.

The shape of the UST curve at these peaks (flat but wrapped around inversion moments) remind us why curves are important as signals, but it is more symptom than cause. To understand causes we need to dig deeper.

I throw in year-end 2018 and year-end 2019 UST curves as food for thought since those markets featured some credit cycle debates as well. In fact, the credit cycle held up until COVID blew it up.

I like these sorts of UST comp charts as food for thought. The visuals force you to think about what was going on in the trenches during those periods. The chart also gives scale to yields and the prevailing coupon starting points for borrowers in those markets. I also drop in a UST curve from late in the day yesterday (10-11-22) as a frame of reference as the UST keeps racing higher across 2022. The movement of the UST curve across each quarter of 2022 has been tough on investors. Fed funds and upward curve shifts make for tough correlation across equities and fixed income.

Summary Takeaways

Current curve: The UST yield curve has been a House of Pain for duration and total returns in 2022 as the curve steadily shifted upward each quarter. The UST curve was hovering around the 3% line in August and is now hanging out in the 4% area. That was a quick move. The UST is now within shouting distance of the 12-31-98 credit peak.

2022 is well above 2018-2019: The UST migration in 2022 has blown past the UST curves of 2018 and 2019 as highlighted in the chart even though the curve took a ZIRP break with COVID until March 2022. We had a mix of inversions in 2019 as well, and fixed investment in the GDP accounts seriously lagged as 2019 was winding down. Equipment had been on a sugar high on tax incentives, and trade war fears (tariffs) were roiling capital budget decisions on where and when to invest. The test would come in 2020. COVID canceled the test.

2007 went from record volumes to a rogue wave of bad RMBS and counterparty pain: I will break out a lot more on the 2007 year and its UST curve gyrations in separate commentaries, but it was wild at the time and in retrospect. The year was one that offered an opportunity for many to change direction and others to get complacent. It was breaking new ground and fully refuted Greenspan’s articulated view that intermediaries and banks do rigorous counterparty work that protects the markets (they usually do and then get overruled by P&L managers. Such was life.). The cost was high as market risk turned into credit risk and collateral panic. The NBER eventually decided (in Dec 2008) that the recession began in Dec 2007, but the credit cycle was dead and buried in June 2007.

The 1990 recession brought a lot of change in UST scale: We are still a very long way from the late 1980s UST levels, but the big difference there is that Greenspan was positioned to aggressively reduce fed funds to support the economy (and really the banks) as the 1990 recession saw further fed cuts all the way into 1992 despite the fact that the expansion was in its second year in 1992. The flexibility to cut in 1991-1992 is not an easy parallel to draw to today given the state of inflation now having more in common with 1980-1981. The idea of fed funds support in a recession in 2022-2023 only works if the inflation rate follows the script of the optimists, i.e., it goes down and not up as it did in the 1970s.

1988 was still a very different time: In 2022, the market remains a very long way from the 1988 curve levels when the idea of an 8% 90-day UST was not a punchline but a reality for an investment alternative. That 8% yield was not too far off from the long-term nominal return on equities.

A few points on credit cycle vs. business cycles across the chart timeline:

Credit cycles can diverge from economic cycles. Given the unusual histories in underwriting, industry fundamentals, periods of bank system stress, shifting fiscal policies, regional variations in economic health (notably the oil patch in bad times for energy), we see some periods where credit cyclical peaks were reached long before equities and even longer before the date listed as the economic peak by industry leaders such as NBER. There is reason the credit market is watched closely now by equity markets as a leading indicator. We saw that lead time in 1989, 1999, and 2007.

The credit cycles in nutshells and nuthouses: We post the UST curves in the chart during key turns in the “Credit Cycle” such as when the late 1980s cycle started to hit the skids in 1989 with a slew of problems. We include the TMT boom cycle of the 1990s. That cycle was a license to print TMT bond deals in HY and the borrowing binge in IG telecom (services and suppliers alike) was literally one for the record books. Bellwether large-cap telecom suppliers (e.g., Nortel, Lucent, Motorola) were becoming like banks with billions in vendor finance loans to speculative tech manufacturing companies and highly leveraged service operators (including in emerging markets). The deal was “I give you money. You spend that money with me.” That was a lot of counterparty risk that ended badly when TMT tanked. The counterparty lessons of the late 1990s were quickly forgotten in 2004-2007. After TMT came the “systemic cycle” of the 2000s with 1% fed funds into the start of 2004 (almost three years into the expansion) bringing a boom in mortgage finance, soaring structured credit, and a blank check for counterparty lines (or it seemed like it).

Cycles within cycles: The bouts of credit market volatility in the post-crisis cycle (starting after mid-2009) took on the tone of “cycles within a cycle” even as the broader economy was not as derailed as some major credit subsectors along the way. European sovereigns were hit hard 2010-2011 and saw a brief relapse in May 2012. With oil bonds as the #1 US HY bond sector, HY took a beating in late 2015 and early 2016 and then saw a major sell-off in 4Q18. The lower UST rates coming out of the 2011 macro panics were still supportive of credit risk appetites after a period of nerves. The plunge in oil did roil HY pricing on major industry risk and redemption anxiety, but low oil can also often operate like a tax cut for the US consumer sector and the broader GDP picture. Even if HY oil bonds get slapped around and regional lenders saw some regulatory scrutiny on their loan books (“criticized loans” etc.), the volatility presented buying opportunities for credit value seekers across periods such as 2015-2016 and shorter time horizons such as 4Q18’s steep sell-off into the 2019 credit rally.

The COVID adventure ended the debates: COVID is the event that killed the credit cycle in 2020 and drove a 2-month recession that included the worst quarter ever at a negative GDP of -32.9% in 2Q20. The -5.0% in 1Q20 also made it into the Top 10 worst quarters ever. COVID also brought the highest one-month spike in payroll declines to over 20 million in April 2020 (the month NBER “officially” dated as the end of the recession). The ability to fuel risk appetites in a ZIRP world was very much on display and went steroidal with the vaccine news in early Nov 2020.

The pre-COVID UST curve activity had left the jury divided in 2018-2019: We plotted the year-end 2018 UST curve as well as the year-end 2019 curve in the chart as examples. We use them as another frame of reference that is useful, with December 2018 marking the last Fed pre-COVID rate hike as the slow attempt at normalization was commenced with the end of ZIRP in December 2015. The end of 2018 was a period of debate on where the credit cycle was headed after a steep HY bond market and equity sell-off in 4Q18. From a pure economic growth standpoint, 2018 started well with 3% GDP growth handles but closed the year under 1% and 1Q19 starting off under 2% GDP growth. During 2019, there was sufficient concern around cyclical trends that the Fed even started to ease again with three cuts in 2019 after the 4 hikes in 2018.The curve was flatter by the end and there was a material downshift also across the curve from year-end 2018 to year-end 2019. The brutal selloff in equities and HY in late 2018 and the defensiveness created by tariff disputes (notably with China but also threats of broader unilateral action by the US) spilled into 2019 and gave the Fed some ammo on fed funds pullback.

The summer 2007 credit brakes get slammed: The housing sector and subprime RMBS get most of the press on the path to the systemic bank crisis, but the broader category of structured credit and excessive derivative counterparty exposure go well beyond housing. The derivative use and hedging exposure generated risks that served to build up bank interconnectedness risk to levels that evoke a few too many metaphors (exploding dominoes, house of wildcards, a fleet of Hindenburgs, alpha boys on a casino night bender, White Punks on Dope, “this is your brain on derivatives”, etc.—you get the picture). The level of activity in corporate credit markets in the first half of 2007 was at a stunning pace and notably in leveraged loans. That leveraged loan volume was not only for record LBOs but also for favorable loan repricing and refi-and-extension deals. CLOs were actually viable products despite the baby-bathwater crowd. They proved it as many other inventions proved very flawed. The sudden state of suspended animation in the summer of 2007 after all of that product flow was borderline surreal.

The 1998 late year struggle, the onset of the default cycle in 1999: The peak of the business cycle was cited by NBER as March 2001 for a 120-month expansion starting after the March 1991 trough. I would highlight the rapidly rising default rate in 1999 (to near 6% by the fall) for US HY, and that came after a very spooky late 1998 that saw market risks spike on the Russia default (and contagion fears across EM). Long Term Capital Management (“LTCM”) counterparty stress, ongoing Asian sovereign and bank system stress that had continued since fall 1997, and some mini panics around Lehman and rumored CDS exposure (proved unfounded) frayed systemic nerves. The LTCM counterparty crunch was leading to fears of a forced collateral liquidation and set the risky credit markets back enough to get the Fed to cut rates in the fall of 1998. The Fed got “informally” involved in crafting a bank and broker bailout of LTCM (a good read on the topic is When Genius Failed).

We will look at the wild fed funds action across the TMT bubble period in detail in other commentaries, but the main takeaway is that inflation ticked up in 1999-2000 and the Fed moved quickly to tighten despite the capital markets turmoil. That put the sword in many HY corporates teetering on default risk. The move to ease very aggressively in 2001 was unfolding as the recession was theoretically over and continued into the next expansion. That set the stage for a lot more credit excess in 2004 to 2007.

1988 credit risk appetites vs. 1989 chaos: The late 1980s cyclical turn seems like a long time ago, but the stagflation and Volcker response of 1980-1982 was even longer ago. I see little question that the credit cycle was over by 1989, so we run with year-end 1988 as our calendar marker on framing the UST curve in the chart. In the fall of 1988, RJR’s record LBO was struck while 1989 saw bridge loans getting hung and broker bailouts unfolding. 1989 saw systemic legislation underway to clean up the financial system (notably thrifts and community banks but also some regionals). As noted in the chart, the Dec 1988 the UST curve is high and flat and is a reminder of how expensive short-term funding was at the time (especially for securities firms in the CP market). Credit markets became unglued in 1989 with waves of thrift seizures ongoing after cascading collapses of thrifts and Texas banks in 1988 and before. The asset quality stress was expanding to regional economies outside the oil patch. California was feeling the strain on the way to regulatory seizures picking up in 1990. The major California thrifts (CalFed, GlenFed, HomeFed, etc.) saw their crises peak later in 1992-1993.

While NBER framed the end of the economic expansion as March 1991, we would highlight that the Financial Institutions Reform, Recovery, and Enforcement Act was signed into law in August 1989. That sure does not signal that the credit market was on solid footing in 1989. The LBO market flunked a few major tests and bridge loan refinancings in 1989 (including the infamous, oft’ highlighted Ohio Mattress “Burning Bed” deal in August 1989). The then record-size RJR LBO was struck in 1988 just under the wire and closed early 1989. As a good milestone for the credit markets and strains of the late 1980s, one could highlight that Drexel Burnham—the dominant HY bond market-maker and liability manager for their highly leveraged clients—filed Chapter 11 in early Feb 1990. In those days, major HY underwriters might not make markets or choose to defend “the other guy’s deals,” and the collapse of Drexel amplified credit market dysfunction. I highlight that this was back in the days of Glass Steagall, so I don’t have the misty-eyed nostalgia that some of the Democratic reformers did in the Dodd-Frank debates.

As we look ahead on our commentaries, we will have a few more memory joggers for the seasoned vets and some history lesson type pieces for the new guys on the block. I was getting those out of the way early. The main goals remain to give context to what is going on today by making clear the path the markets have traveled in a time when lookbacks are important to sort through the BS. Sometime the actual history clashes with the conventional narrative on cycles, and the Fed and the UST curve movements across cycles might surprise some. There will be comparisons of today’s markets with the Volcker stagflation years, with the systemic crisis years, with the TMT bubble, with the housing and mortgage crisis, with the Yom Kippur War and Arab Oil Embargo backdrop, and with the sovereign stress and Eurozone anxiety of 2010/2011/2012.

The market today could even see parallels in the 1992 currency crisis when the UK dropped out of the Exchange Rate Mechanism and Soros went on to print some billions in currency winnings as currency contagion spread. I was in a taxi in London when the UK announced its ERM and the news broke in Sept 2022 (Lehman was putting on a conference). The driver wanted to engage me on the topic (London cab drivers are a different breed than NYC—no offense intended). He voiced his concern about a sterling crisis and soaring overnight interest rates. That was 30 years ago. Here we are again. With the largest land war since 1945 raging in Europe, the flexibility to address currency issues may not be so easy to find with the US dollar marching (flying?) to its own beat. Brexit bad blood might not help. That is just one more thing to digest in global macro variables.

Overall, that is a lot of past vs. prologue wood to chop.