Fed Funds vs. PCE Price Index: What is Normal?

We look across the cycles at fed funds – PCE. The negative relationship post-crisis stands out as an anomaly.

Summary

The historical relationship of fed funds vs. either CPI or the PCE price index is a matter of historical record, and there is relevance to today’s inflation battle. It is a challenge trying to reconcile today’s market with a multi-cycle timeline clearly showing fed funds is typically higher than inflation metrics. While the “fed funds - PCE” gap is narrowing in the direction of the long-term median, it is still a long way off even after factoring in the expected 75 bps in fed funds for November.

I looked at this history for fed funds vs. CPI in an earlier note (see Fed Funds-CPI Differentials: Reversion Time?), so I refer you to the details there. The same points apply here. Inflation metrics are always important in this market, but the Nov 2022 inflation releases (first CPI on Nov 10, then PCE Dec 1) will be anxiously awaited as some more bearish terminal rate theories might start flirting with 6%.

The market will want to see some sign that the inflation number will bring some “help from above” while fed funds keeps climbing from below. Something has to give on rates moving higher faster or some evidence that inflation is feeling weakness in demand or supply chains that are unclogging. The eventual “base year effect” will help the rate of change in prices, but household budgets will still feel the step-up in the price vs. volume trade-off with real wages and purchasing power lagging.

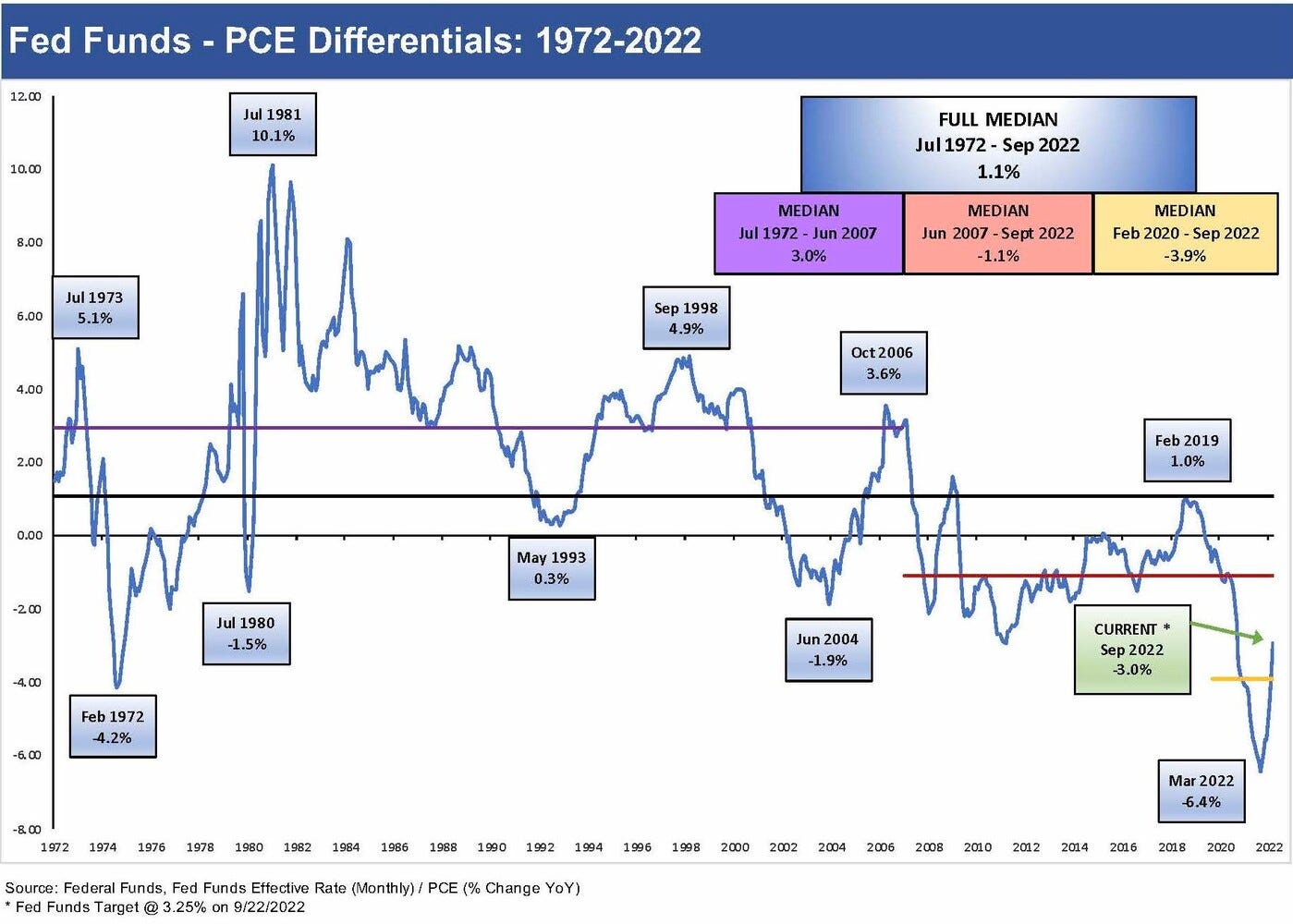

The above chart shows the PCE version of the fed funds vs. inflation differential that mirrors the earlier fed funds vs. CPI differentials we already reviewed. The simple conclusion is that the long-term fed funds rate median is higher than the PCE price index. Using the 1972 to 2022 median, we see fed funds 1.1 points above PCE. Using the 1972 to June 2007 timeline, we see the differential rise to +3.0 points. As a reminder, we use June 2007 as the peak of the “credit cycle” ahead of the unraveling into the 2008 credit crisis.

The post 2007 median number (Jun 2007 - Sep 2022) on the chart turns negative to a -1.1 points median (-3.9% post COVID) as the market moved into a crisis management stretch led by the Fed, ZIRP, and QE. The problem with such a protracted period of ZIRP (ended March 2022) was that inflation got a big head start. The current FF-PCE differential is at -3.0%, and that differential will get trimmed down with the FOMC action this month. So the trend is that the market is moving in the right direction but needs both headline and core inflation to cooperate. The 6.2% headline PCE and 5.1% core PCE bring the differential closer to the median, but the headline CPI is still a long way off.

With a winter energy crisis ahead in Europe and a lot of questions hanging over food on a global scale, it is hard to get too optimistic on relief. Calling energy and food “transitory” these days has a very negative feedback loop guaranteed. The raw materials factor in the petrochemical chain (which seems like it is everywhere) and the basic realities of freight costs (fuel costs on the sea, air, and land) are not easily dealt with as pricing power is still very much in evidence downstream (see Market Menagerie: Freight and Logistics).

History says “fed funds is too low with inflation this high”…

The comparison of fed funds to CPI or to PCE tells a simple story. The post-crisis period has been distorted by monetary and fiscal support and sorting those pieces out in an inflationary market has never been done before. History may not apply, but then someone at the Fed has to say WHY that is the case with their outside voices. Supply-demand relationships are still Econ 101. That has not changed.

I tend to watch CPI more closely than the PCE price index for a number of reasons. Maybe it is simply because I came of working age in the 1970s and CPI ruled the headlines. CPI also rules many contracts, for example, COLA clauses in collective bargaining, interest expense benchmarks in some consumer credit lines, inflation clauses in real estate rentals, and in retirement benefits programs. The market gives it more attention even if the Fed does not rank it #1. Then of course the political discourse and media focus more on CPI.

For my purposes, the Personal Income release that comes late in the month offers just what the headline says – Personal Income data – and that is always useful in an economy where Personal Consumption Expenditures is over 2/3 of GDP. The PCE price index is something to watch because the Fed does. The President is not going to give a stump speech and say, “Did you see the PCE price index is down?!” This is because the PCE price index is not part of the consumer/voter vernacular. He also would not say that since the headline PCE was flat in September anyway and core PCE was up!. We are at least down from 7.0% on PCE from June.

CPI vs. PCE. Does it really matter?

Below I look at the CPI vs. PCE history. I am not wading into the conceptual tar pits of the question of “Which is better?” That is above our economics pay grade. In the end, the FOMC actions are all supposedly data driven, but a forward-looking view on what might or might not work is also a part of the policy design. There are too many examples of differing views across FOMC members, so we need to conclude that there are a lot of assumptions and subjective inputs. On numerous occasions the Fed’s leading minds cannot even agree on what they are looking at. Some of the differences are based on different theories and some are based on bad assumptions, some just have models that don’t capture certain types of risks. Economists are sometimes in the business of naming models and formulas after themselves, so they take these things very seriously.

My favorite example of dramatically differing views is from the August 2008 FOMC meeting (as recorded in the transcript). That meeting was just before the mid-Sept meltdown of Lehman, the acquisition of Merrill by BofA, and the bailout of AIG. A couple of FOMC members were on record saying systemic risk had essentially been eliminated. I bet those economists hate transcripts now. A few said the biggest threat was inflation (deflation shortly followed). A few were worried about the banks, and a few were not. To her credit, Yellen was very worried about the banks. We all know how that one ended. Systemic risk was brutal, banks were teetering on a liquidity crisis, and bank/broker interconnected risk was turning into a noose.

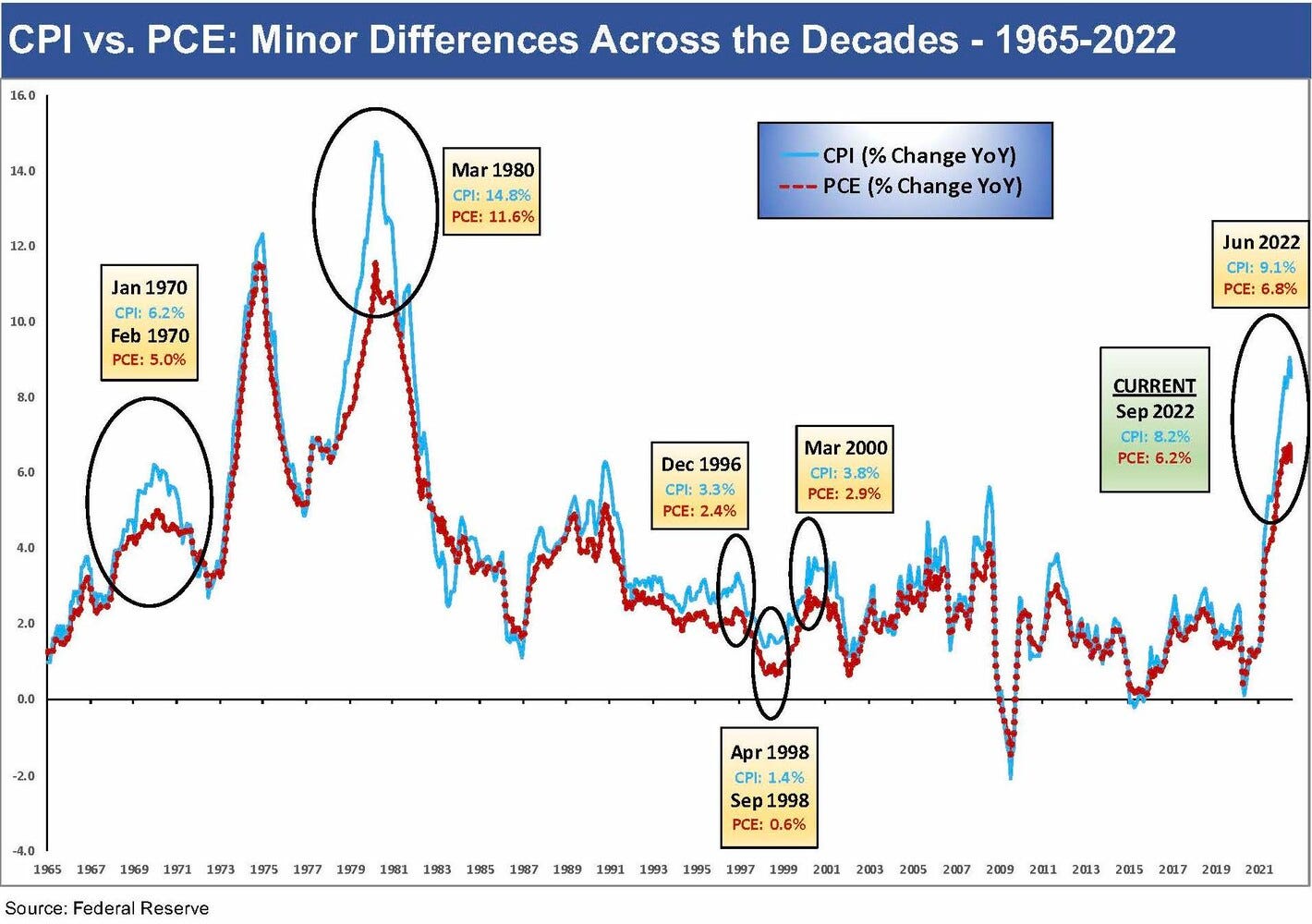

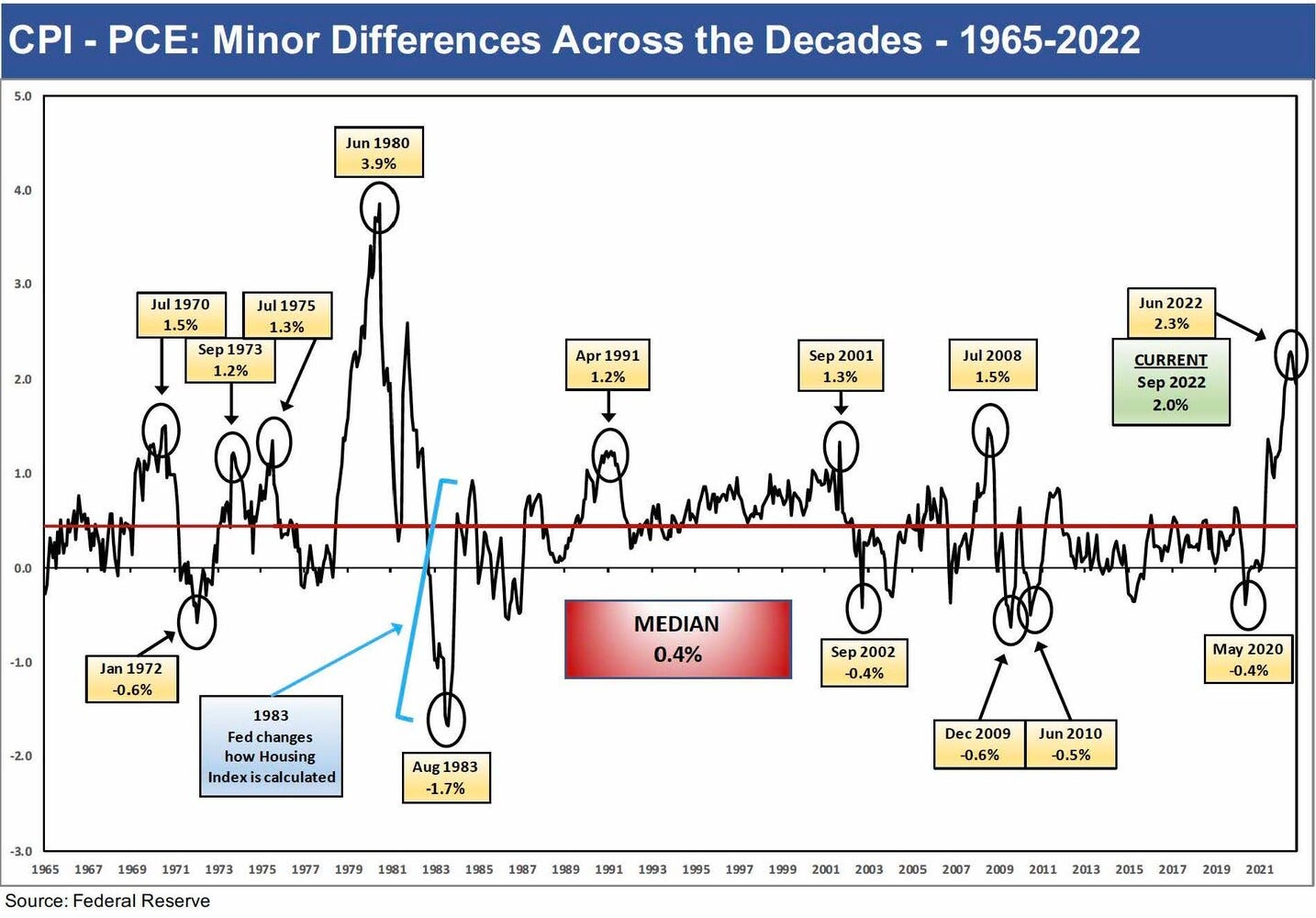

The headline CPI and PCE numbers across time are tracked in the above chart as a reminder not to overthink the nuances of the CPI vs. PCE part of the equation in terms of the differentials with fed funds. Economic deep thinkers have been writing about the relative strengths and weakness of CPI vs. PCE for years, and there is no shortage of literature on it written by very smart people. The chart above drives home that the two track very closely with some brief periods of differentials moving higher. It ends up like the Miller Lite commercials of the 1970s of “Tastes great or less filling.” If it is the only beer being served, you drink it anyway. CPI has the advantage of being served first each month. The BLS data is also more filling.

It is important not to lose sight of what I am focusing on, which is fed funds historically has ridden higher than inflation (CPI and/or PCE). That was notably the case when inflation fighting was underway with Volcker. We looked at the “reasonably normal” periods for this relationship in earlier commentaries that focused on the fed funds target rate vs. CPI. We framed the 1990 to 2007 period (See Fed Funds, CPI and the Stairway the Where?), and we also looked at a stretch of the differential in our commentary on Greenspan's First Cyclical Ride: 1987-1992. The 1980s period even after Volcker was also a stark case of fed funds being well in excess of inflation.

I say “reasonably normal” since there is little in fed funds history that captures the ZIRP and QE effects after the credit crisis of 2008. Just when we thought it was safe to go back in the tightening waters, COVID came on. Then COVID jumped right into a monster risk rally and demand rebound even as Delta (COVID) roiled spring 2021 and freight and logistics subsectors were way out of alignment. Supply-demand disruptions ruled the day. The swing factor was prices for many goods and services.

Looking back across the decades, the Volcker inflation period was also not too normal, but inflation essentially ran from 1973 to 1982 in varying degrees of severity. Volcker applied the doctrine of massive retaliation against inflation from 1979 to 1982 and came away victorious. Fed funds was allowed to float in his battle plan that focused on monetary aggregates, but it generally floated well above headline CPI.

Volcker kept the heat on, and his actions were the closest thing we have to a template. The lack of a clear history for the right formula makes it easy to be skeptical that everyone on the FOMC knows exactly what to do. They all may be in the top fraction of the 1% of gray matter, but they all argue about topics all the time. That says something.