Fed Funds-CPI Differentials: Reversion Time?

We look across the cycles at fed funds – CPI. The negative differential in 2022 is an anomaly vs. pre-crisis years.

In this series of charts, we look at the differential between fed funds and CPI across 50 years, highlighting the critical trends seen during the stagflation years. We ask a few reasonable questions that are worth considering:

How should we view the relationship between the fed funds rate vs. CPI over the past 50 years? Is it just a reflection of the conditions on the ground? Or a history of overshooting?

If we see that the median fed funds rate was higher than CPI over those 50 years and more materially so for the ~ 35 years prior to the credit crisis (1972 to 2007), should this be viewed as a normalized relationship? If so, was the next 15 years abnormal?

If fed funds has been lower than CPI since the credit crisis as a normal response to a set of conditions (credit crisis, COVID), have those conditions now changed dramatically in the face of inflation?

Was COVID just one more extreme anomaly that kept the more normalized relationship on hold?

If the relationship of higher fed funds vs. CPI was more pronounced during the Volcker inflation-fighting peaks of 1980-1981 that was slowly dialed back after those peaks, does that tell us something about what it will take now to fight inflation—when fed funds recently stood 5 points below the target fed funds rate?

If the current differential in 2022 for “fed funds minus CPI” looks more like early 1975 (near the end of Nov 1973-Mar 1975 recession and the June 1980 misery peak, what does that tell us?

The Fed needs to do what it deems necessary for its dual mandate and financial stability focus, but past relationships between the fed funds rate and CPI tell a vivid story and offer important context for what it all means today.

The chart series below looks at the multicycle timeline for the differentials between fed funds and CPI. As we gear up for the September inflation numbers on Thursday, the debate on Fed intervention—timing and magnitude – will continue whether we see a reassuring signal or another high anxiety moment like last month. Either way, the relationship between fed funds and CPI looks well out of alignment right now. In theory, the fed is very committed to beating back inflation, so normalizing the relationship may be a front burner issue sooner rather than later.

In my view, the current gap between fed funds and CPI raises alarms after setting a new record in March 2022— reaching -8.3% (fed funds minus CPI). Either history is wrong, or something has to give (and give a lot in relative terms). In theory, the forward view of how the Fed wants the world to look has more in common with the pre-2007 years. The last time a stagflation period of this scale was seen in the US occurred in the 1979-1981 stretch and the charts make it clear how aggressive Volcker was in moving to beat it back. The tools used in 1973-1975 did not get it done. Volcker did not screw around, and he went for the victory over the inflation of the time—a victory that also triggered a double dip recession.

Being unforgiving on inflation worked for Volcker and successors for years, but that before the systemic crisis forced the Fed into protracted ZIRP and QE mode. That slow move to normalize has been beaten to death as a topic over the years, but the relationship of fed funds to inflation is still a long way from the past patterns.

Key Takeaways

The forecasts keep rising on terminal fed funds rate: Fed funds have been running higher with frequent material upward revisions since the start of the year (reminder: ZIRP only just ended in March). The timelines and magnitudes have since been pulled forward. Some on the street have forecasted a mid-4% handle early in 2023 and some calling for 5% and higher. The September release showed a 4.6% FOMC estimate.

Inflation gut check this week will test the differential forecasts: The pressure and threat of negative inflation surprises ahead can come from energy on supply-demand issues (OPEC production setbacks are already here) or simply a cold winter (weighs most heavily on gas). The hydrocarbon chain (oil, NGLs, natural gas, and downstream petrochemical derivatives) is as pervasive across goods production as well as the myriad other cost inputs it brings. That sensitivity to the effects beyond the pump and power bills is catching on. In the inflation swing factors that we can also check off, we see food supply-demand imbalances, perceived labor wage impacts on the goods/services pricing dynamics, more supplier chain disruptions (China tension), or simply any signs of demand resilience across many subsectors. If employment remains as resilient as evidenced last week, demand will still be a hot topic. In some sectors (housing) the direction is negative. In other (autos, leisure), the story is more complex.

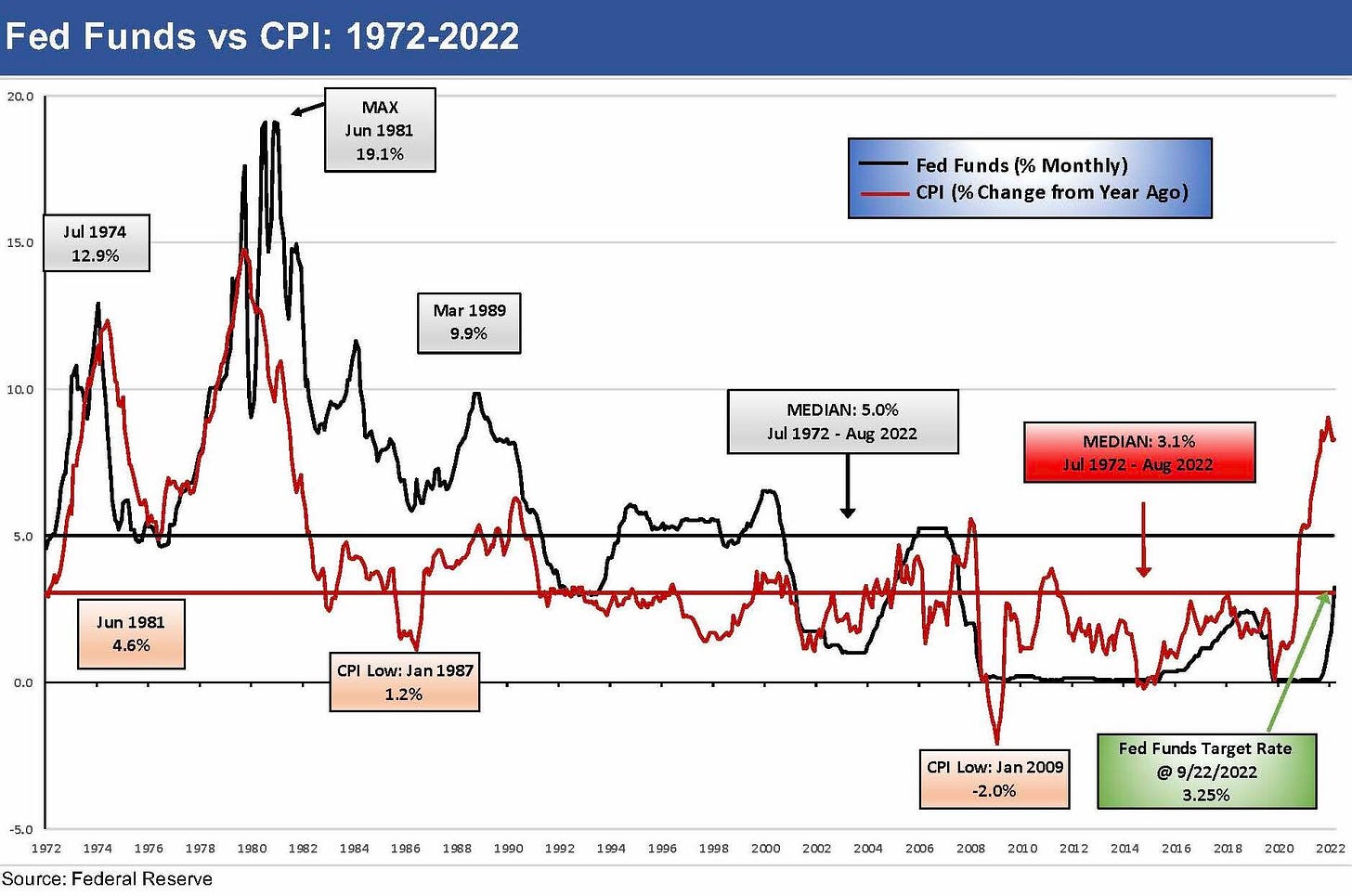

Higher fed funds target vs. materially higher CPI: We see this chart as one of the more worrisome of the time series collections on inflation. The above chart plots “fed funds minus CPI” (“FF-CPI”) from 1972 to the most recent August inflation number (released in Sept 2022). The effective fed funds rate (monthly average) is used across the time series, but for the September 2022 differential, we drop in the new 3.25% fed funds upper target and frame it against August CPI (Sept CPI release this week). This chart just zeroes in on how the numerical differential tracks across the decades. Below we provide additional charts that show the data used to generate this net number. The extraordinarily aggressive fed funds number of the 1981 period shows a differential of +9.5% in June 1981. Meanwhile, the lagging Fed action of 2022 is evident in the -8.3% fed funds-CPI differential of March 2022. The need to play catch-up is self-evident.

Differential looks more like 1975 and 1980: After FF-CPI gapped to -8% handles with March 2022 numbers, we saw some narrowing on Fed actions. The difference still stands at just over -5% currently. This is in line with February 1975 and June 1980 levels. We recognize that the Fed sets its sundial by PCE Inflation (headline and core), but the shortfall of fed funds from current CPI begs some consideration at a time when the natural comps should start to be directionally moving toward how the problem was addressed during the stagflation years (i.e., FF >CPI). The pre-crisis, long-term median of the FF-CPI gap from 1972 to the mid-2007 credit cycle peak stands at +2.2% vs. the current -5.1%, and that sends signals that either fed funds needs to go up substantially or inflation needs to go down materially—all during a period fraught with highly uncertain underlying variables. The post-2007 median through 2022 is -1.1% as we enter a period ahead where the inflation spike changes the rules of the game for the Fed’s post-crisis COVID recovery policies.

Instead of the net differential, the chart above looks at the two moving parts of fed funds and CPI from 1972 to 2022. For the full period, the median fed funds rate of 5.0% exceeds CPI median of 3.1% by just under 2%. This would appear to affirm the caution voiced by more than a few economists these days. When we compare medians before and after the credit crisis, a different pattern emerges. Before the credit crisis, the median fed funds was materially higher than median CPI. Post-crisis, the relationship completely flipped with ZIRP, QE, and Fed balance sheet hyper-growth.

What comes next? The question is an obvious one really. I believe that the relationship must revert, but this will depend on how committed the “new Fed” is to fighting inflation, and whether they will follow in the footsteps of “old Fed” to make it happen. The playbook used by Volcker was aggressive and not as applicable today, but the floating fed funds rate moved in a direction that notched up a victory. Certainly, the pressure in on. There is no shortage of hawks running around making speeches about the need to see some success here.

The chart above zeroes in on a narrow time frame (1972-1983) during the stagflation spikes of the two oil shock periods. The policy moves demonstrate how Volcker established his credibility after his arrival in 1979. Volcker’s actions in the markets after the second oil shock were viewed by many at the time as draconian but in hindsight can be seen as necessary evil. This current market is the first time since 1983 that the Fed has seen such high inflation rates. As a reminder, Volcker took the helm in August 1979, approximately eight months after the Shah got the boot from Iran and the second oil shock was underway. A few trips to 20% fed funds made a statement as he focused on his money supply strategy and let fed funds swing in a very wide range.

In the chart, the gap between the black fed funds line and the red CPI line in the early 1980s battle tells a clear story. Volcker was determined to make it happen—there’s no substitute for victory—and in so doing managed to transform the public’s expectations of the Fed. As history has shown, keeping leaders in Washington happy wasn’t high on Volcker’s list of priorities. Nonetheless, his reputation held firm as he literally reshaped inflation risk until he moved on in 1987.

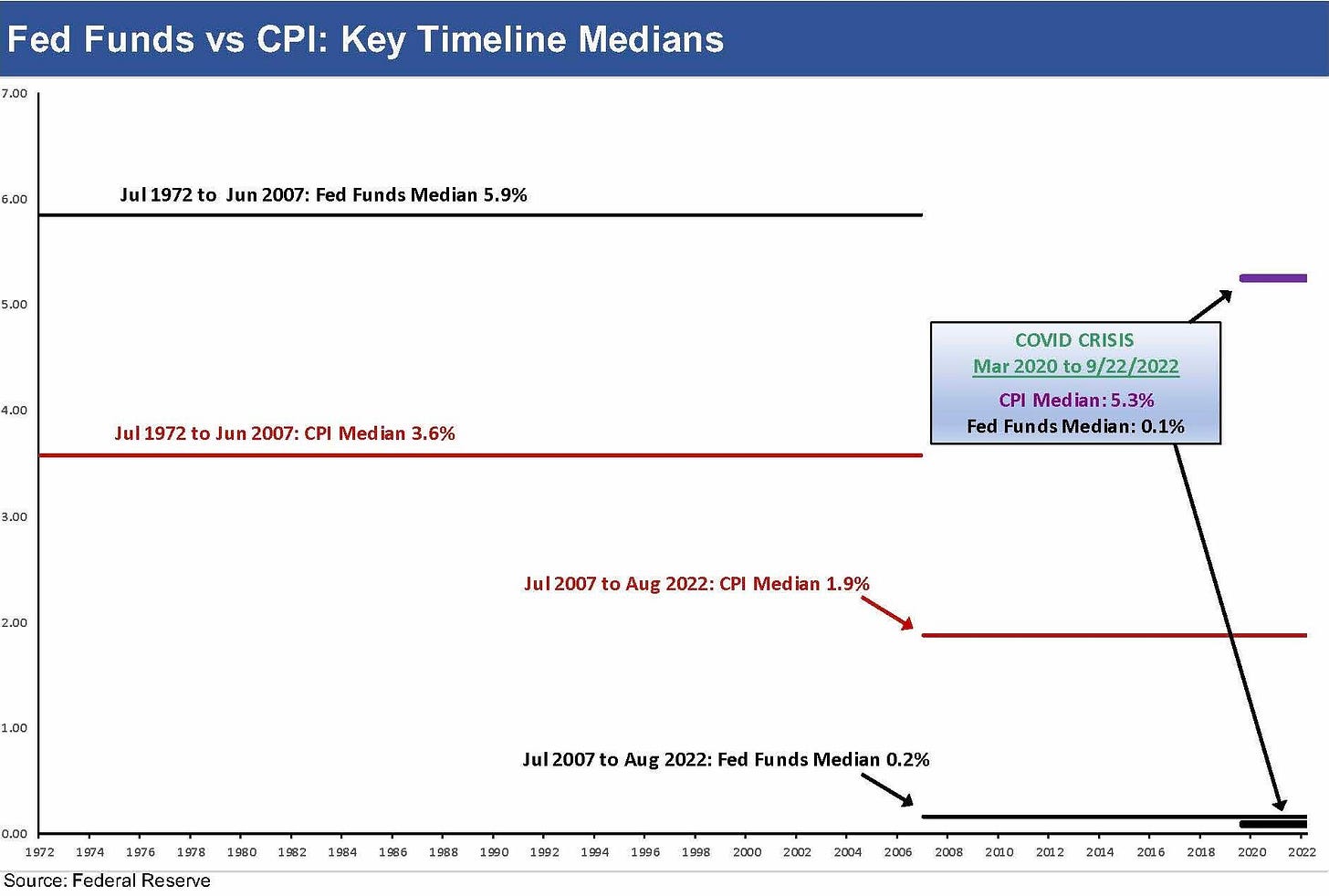

As part of a “before and after” exercise, we also plot some shorter time horizon medians above for fed funds vs. CPI. The above chart frames the medians for three key timelines to highlight which periods altered the longer-term historical relationship.

Key takeaways

1972 to the credit market peak in June 2007: While one can easily argue there was nothing normal about the 1970s and early 1980s stagflation years, we can start to get into semantic gymnastics around what is normal. The most recent bout of inflation would indicate that high inflation and energy sector turmoil has been seen before…here we are again in 2022. In contrast, we would argue that the systemic bank crisis in 2008 and near existential threat of bank interconnectedness in the age of derivative counterparty exposure was very abnormal. The modern era of capital markets arguably includes the 1970s even if the modern credit markets were more of an early/mid 1980s thing. The median effective fed funds for 1972-2007 is across a period of ~35 years and was 5.9% while CPI was 3.6%—even with the inflationary spikes. Positive real fed funds rate makes intuitive sense. The commonsense element applies.

July 2007 to August 2022: The world changed in late 2008 when the cascading domino effects almost took out the global banking system, with the US and major European banks first in line. We’ll be looking at the credit crisis in detail in plenty of other commentaries, but the level of counterparty risk exposure vs. bank capital was mind-blowing in retrospect even if just looking at the receivables from AIG to the major banks. The Fed had a lot to worry about but financial stability and the bank system continuing to breathe was at the top of the list. The supportive Fed and ECB action and legislation in Washington and Europe saved the economy (global and regional) from 2008 to 2019. The reversed relationships of Fed funds and CPI was no coincidence when the median fed funds rate was essentially ZIRP. The Fed balance sheet size went ballistic in its growth in support of market liquidity and the shape of the UST curve reflected that even as buying MBS onto the Fed balance sheet supported what eventually became a robust housing rebound.

The transition to the COVID crisis through August 2022: Then came COVID. The Fed had a playbook from the crisis to bolster market liquidity and mitigate the threat of protracted risk aversion crushing markets. The Fed and Congress needed to make sure COVID did not set off a default death spirals that could some with a severe credit crunch, proliferation of even more bank line drawdowns, and endemic defaults from borrowers (including households) to preserve cash. When COVID slammed the brakes on so much economic activity and shattered records for payroll declines in a single month, the Fed had to pay attention. The dual mandate very quickly became “not so dual.” We know how that played out once the vaccine was announced as growth stocks soared, the most speculative equities soared, and supply chain problems distorted supply-demand balance in what became a “demand shock.” Demand spiked, supply tightened, container shipping companies minted cash, producers passed through all their cost increases (and then some), and inflation creep ran from the shelves into the wage expectations of a tight labor market.

Monetary and inflation transmission mechanisms can be complex when flowing into supply-demand dynamics, but profit maximization desires are not a major mystery. Companies raise prices when they can. Certainly, cost pressures were a significant factor, but they also raised them for other reasons—because they could. Nixon took a shot at that type of problem with wage-price controls. It didn’t work. The debate on active government intervention in market pricing has been making the rounds again in the financial media and on the policy circuit again, and free market advocates are rounding up twice the usual number of policy experts to trash it. There will be a lot of speeches about price gouging from senior Democrats and the GOP will talk socialism. Away from the performance art of politics, the question will still get back to “Will the Fed be aggressive and risk the recession sooner rather than later? And if they do, will they go Full Volcker on the challenge?” I think it will take more than few negative surprises to get much more aggressive, but the FF-CPI metric tells a story.