Greenspan’s Last Hurrah: His Wild Finish Before the Crisis

The Greenspan response to the TMT bubble saw rates go too low for too long into the expansion. Trouble followed.

Summary

There is always going to be a wide range of opinions on Fed policy. The Fed has a history of what some may view as “excessive tightening.” For example, some believe Volcker went too far, so he could be sure inflation was beaten. (If he hit the mark, we are in for more trouble in the current market). History also shows some false alarms such as 1994 under Greenspan (see Bear Flattener: Today vs. 1994 and Aftermath). “Too tight” might have been the case at 9% handles in 1989. In contrast, the market has felt periods of “excessive easing” such as 1991-1992 under Greenspan, 2001 to 2004 under Greenspan, and too much post-COVID ZIRP from Powell.

The old rule around Fed policy action is that easing generates growth and “excessive easing” causes bubbles. Tightening fights inflation but can cause recessions. “Excessive tightening” and broad credit contraction can create a world of pain (or even a depression). The period of rapid tightening from the 1.0% to start 2004 through 2006 was too late to derail the juggernaut of excessive leverage, manic origination of structured credit products (cash, synthetic, derivative-heavy, etc.). That of course led to astronomical growth in counterparty exposure and a very risky level of bank/broker interconnectedness.

The 2001-2002 easing set the table for trouble…

In this commentary, I look back at the major moves in the yield curve across 2004 to 2006 as the Fed played catch-up on fed funds and the front end moved higher very quickly. The first section breaks out the UST curve shifts and monetary policy actions at the Fed, in CPI trends, and in the fundamental backdrop. The 2004 to 2006 timeline is the main focus of the piece. The second part is more self-indulgent and summarizes my own view of the crazy times in 2004-2007. The financial aggression and ensuing tumult are now legendary in songs and funeral dirges.

The 2004 to 2006 excess began with the low and steep curve coming out of the mild recession that “officially” ended in Nov 2001. We look at these cyclical and recession histories in other recently posted commentaries (see Expansion Checklist: Recoveries Lined Up by Height, Business Cycles: The Recession Dating Game). The relevance to today is more about how any FOMC members can talk themselves into alternative courses that are rooted in somewhat subjective handicapping. I have spent some time flagging how the multicycle history generally shows fed funds above CPI (PCE is also, but we have not published that one yet), but fed funds is not close to CPI or PCE in the current market. That is a scary thought considering the reactions to hikes to date with 6% a long way off. This history leaves a lot of room for guesswork in this current transition period. The excessive easing history I discuss here is another one that some look back on and grimace. Hawks worry about another dovish detour ahead.

Begin at the Beginning…

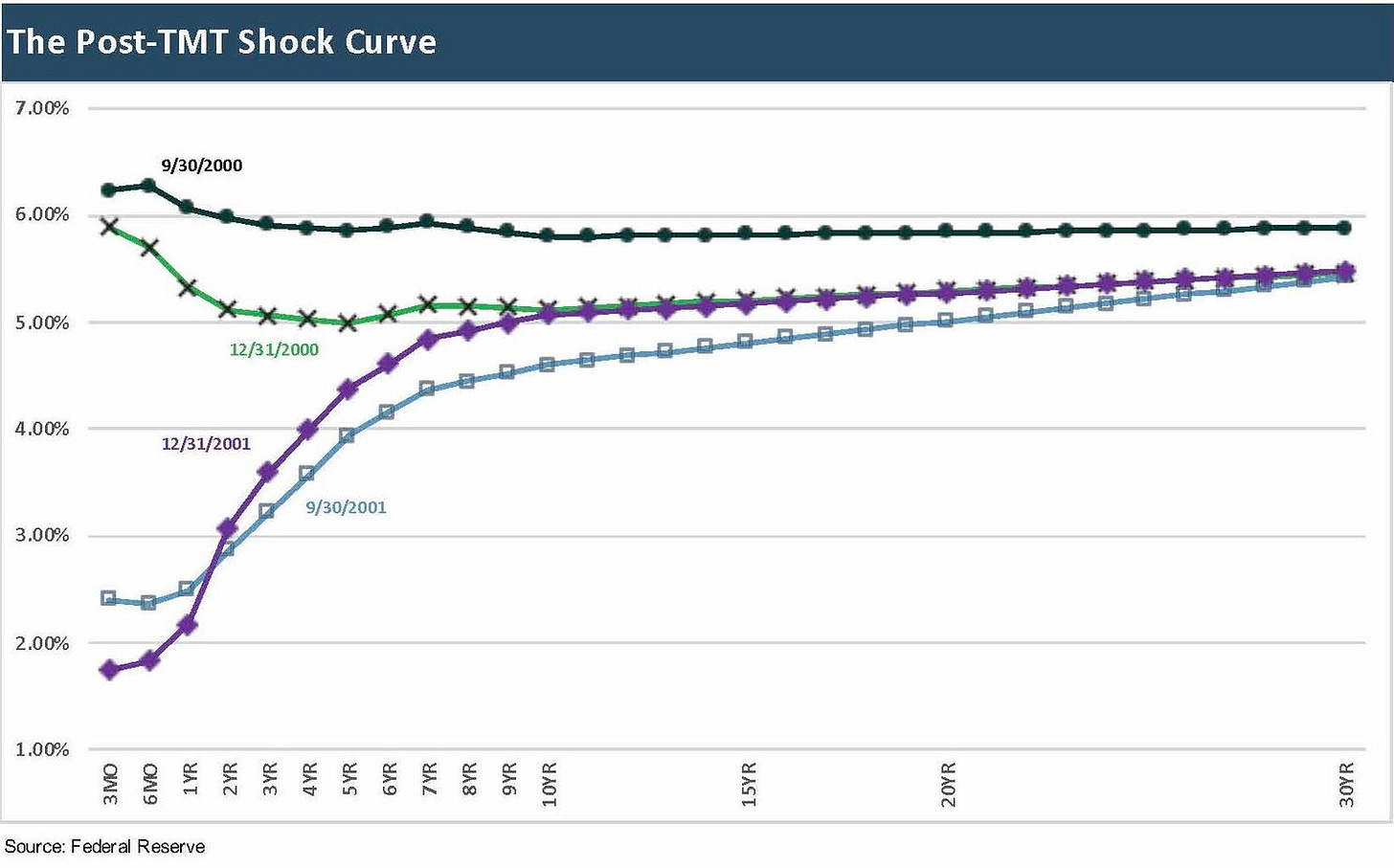

The above chart shows the lead-in period of 2000-2001 before the tightening cycle of 2004-2006. It is a long way down on the 3M UST from 3Q 2000 to 4Q 2001. The front end kept going lower from there through 4Q 2003 with the Fed pushing fed funds down. We saw fed funds move from 1.75% to 1.25% in Nov 2002 and from 1.25% to 1.0% in June 2003. Fed funds stayed at 1.0% through June 2004. I touched on the Fed’s post-TMT moves in part in a separate commentary (see Fed Funds, CPI and the Stairway the Where?), but 2000-2002 needs its own dedicated drilldown some other time.

As a reminder, late 2001 saw Enron and summer 2002 saw WorldCom. Many questions were raised. 2002 was an unusual year for me since I ended up in Enron hearings at the Senate in March 2002 and one of the presenters at the SEC Rating Agency Roundtables in Nov 2002. At the Enron hearings, I was there to talk about shortfall in how the parties performed. I could show my mother I got quoted in Smartest Guys in the Room, but I found little value otherwise in the whole process. I find Washington a very strange place.

This was the period that led to more research reform and regulatory change, and independent research had a role to play. Given what ensued in the following years into 2008, the lawmakers and regulators had not prepared for the trap doors in the system. Talking to committee support personnel (counsels, etc.) was interesting along the way (I did a rerun with the Senate in 2006 and House in 2005, but after that I tapped out with the 2009 SEC roundtable). The Congressional hearings seemed more about political choreography for reasons I picked up around the backroom chatter. The wheels don’t turn much and they usually spin.

Why the UST migration histories?

I have been producing these historical UST migration commentaries for historical bookkeeping since I always hear questions such as “What is the current cycle like from past years?” These UST charts are produced to offer my own perspective on past cycles and whether some relevant signs can be found in a business cycle, a fed tightening/easing cycle, or some very distinctive credit cycle. It is tough to find a useful comp to the current cycle since the inflation factor dominates the story today. That means the late 1970s and early 1980s as a comp, and that period is never reassuring given the extreme policy actions. Meanwhile, the economy, the world, the regulatory backdrop, and the players are so different now than in the Volcker years.

The journey from 2000…

The challenge in 2000 as the NASDAQ peaked (March 2000) involved those of us in the markets trying to frame the downside if fundamental credit risk started to spiral. In the Spring of that year, I left Deutsche Bank where I was head of Global Credit Research to start CreditSights with some colleagues. We did not know how long the fuse was and how big the pile of munitions was going to be on the other side, but the fuse was burning bright. It did not look good. Something was going to blow. With the arrival of the internet, a window was open for independent research. “The deals too far” from 1998 and early 1999 was well past the expiration dates. The default cycle was on by fall 1999. It got worse quickly on the credit side across more than just TMT.

Despite the bad deal cycle, the easing in 2001 by Greenspan was either a major overreaction or an insurance policy. Greenspan did not know how long the fuse was either, and perhaps he saw a bigger pile of “things that go boom” on the other side. The summer and fall of 1998 (LTCM, Russia default, EM contagion) was a reminder of the hidden risks in a world of derivatives and leveraged, less regulated brokers. History indicates Greenspan was caught flatfooted in 1998 on counterparty risk issues.

The due diligence and audit system broke down…

As the markets played out, the default cycle was protracted and brutal, fraud was a little too abundant, and faith in auditors made senior partners look like they went a few rounds with Mike Tyson. It was so bad that a major Swiss reinsurer pulled their auditors into an offsite to revisit financial risks and look for red flags (liability insurance claims were not small). I was a presenter at one session of a conference on the side of some mountain in Switzerland. As a former CPA who worked on some dicey leveraged clients in the early 1980s, I was skeptical and knew that partners sometimes run their own little fiefdoms.

Such cases of audit meltdowns are very rare, but the legal response put Arthur Andersen under and punished a lot of innocent people. That was a time when Spitzer and others went for political overkill and filed criminal charges against the parent and not just the individuals. That tossed tens of thousands of people out of work. That is like carpet bombing a city block to get rid of the rodents. Meanwhile, for the investment banker it was business as usual. The banker was still calling his car service for the ride back to Greenwich. Auditors and research analysts took the fall.

The problem with Greenspan’s scale of easing during this period was that the recession was the mildest in the postwar era. It was more a bad underwriting cycle (“bad” is too kind). The market quickly recovered after the last round of horrors in the summer of 2002 (WorldCom fraud, Tyco noise). There were lots of hearings and change driven by Washington such as Sarbanes Oxley and later the Global Research Settlement.

The expansion was on in a big way in 2003.

Hurry up and tighten…

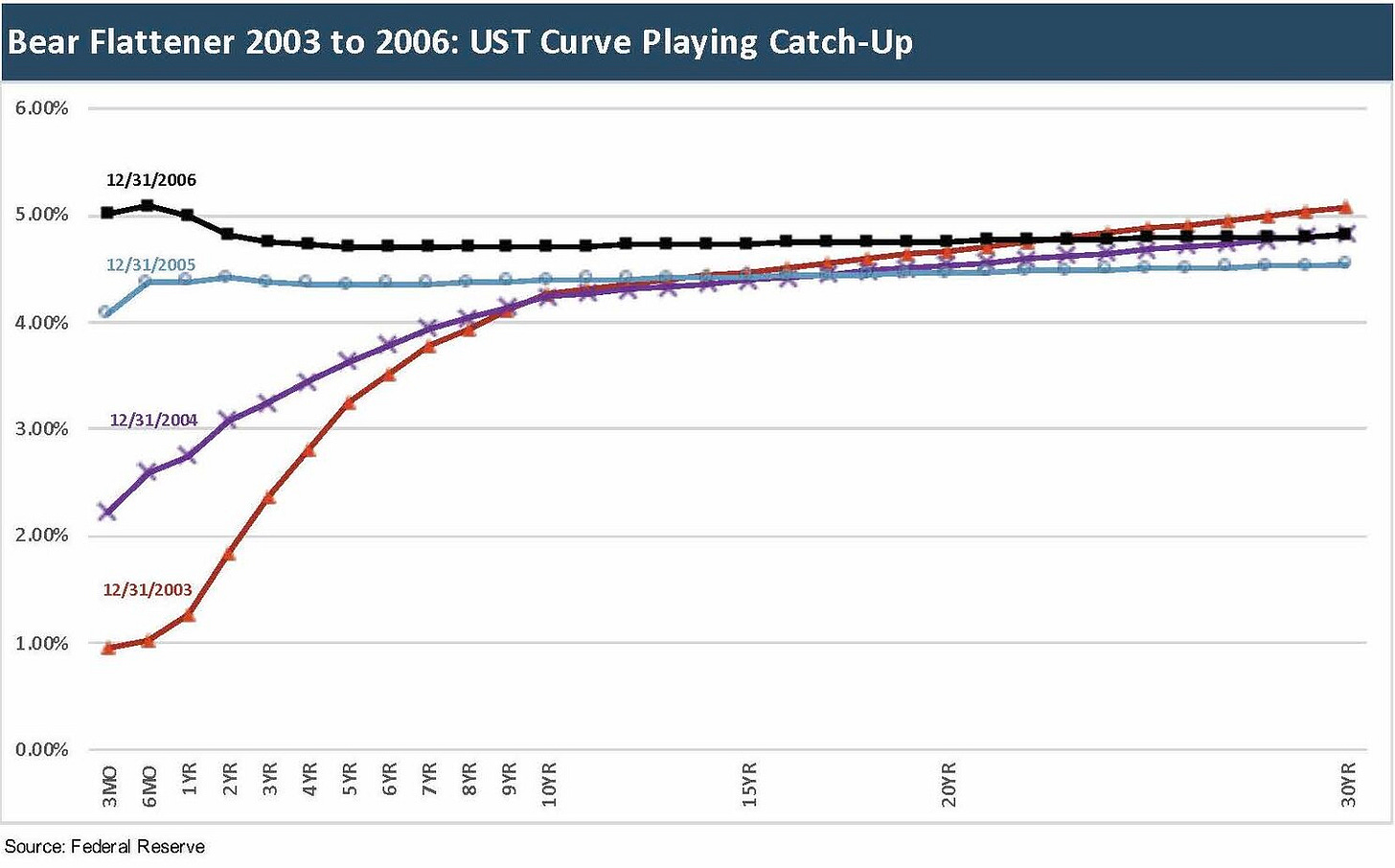

The above chart frames the UST curve shifts across the bear flattener (short rates rise faster than long rates) that unfolded quickly from the end of 2003 to 2005 and then into an inversion by the end of 2006. The pace of the Fed tightening moves was not as frantic as the housing boom and the tsunami of new mortgage products that hit the market. The array of products and the industry dynamics challenged the process of framing risks. Terms such as “scratch and dent” RMBS was new to my vocabulary.

The ability to print so many leveraged loan deals and engage in record-sized LBOs and CLO origination was enhanced by the floating rate economics and the risk symmetry for secured credit investors with the curve clearly heading higher. In the end, the CLOs held up very well across the crisis, but the structuring imaginations ran amok.

As an example of a “product too far,” CPDOs (Constant Proportion Debt Obligations) was one of the more over-marketed ideas by triple-jointed quants. The perfect math boards came with a general lack of common sense around the risk of price dislocations and the efficiency of pricing in risky credit. The reality of credit market liquidity and pricing dynamics would upset their little world of assumed secondary liquidity in risky OTC credit markets. They started blowing up in 2007. The financial engineers found willing partners in the rating agency crowd as all-new products and fee streams were created. Those stories have been told around the circuit for a long time and is pretty much old news.

The problem was not systemic corporate debt across nonfinancial companies….

Even with the record volume set in mortgages and structured credit, the overall systemic corporate debt vs. GDP was not excessive despite the outlying credit “dogs” that are found in every market. We know how it all ended for mortgages, banks, and HY default rates (14% handles in 2009 at a lag), but the root of the crisis was not in the cash corporate bond markets regardless of the noise of made by some of the Volcker Rule architects. The sequence was systemic risk blowup came first, then credit contraction and risk aversion. Then the credits in the corporate market followed along on the road to perdition.

The main events that set off the crisis were mortgages, derivatives, and bank/broker interconnectedness risks (the domino collapse thing). Add in collateral “purge risk” in hedge funds from theoretical margin calls and toss in questionably supported asset backed commercial paper tied to implied bank support, and the use of “systemic” risk has absolutely no hyperbole in its use. In terms of learning curves, the 1998 LTCM systemic counterparty lessons were not retained. There were too many fees to print in 2003 to 2007.

The slow but steady Fed tightening cycle…

While the 2001 easing frenzy was one for the record books, the follow-on tightening across the 2004 to 2006 years was rapid but in smaller increments. Growth was steady and solid across this period of expansion, but the cycle ended up much shorter than the 1980s and 1990s expansion. CPI was trending modestly higher, so that was a factor as fed funds ticked up on average each year. Overall, the tightening still took on the appearance then and now as an exercise in playing catch-up. The damage was already underway. Like an old horror movie, the phone rang, and the Fed realized “he is in the house.”

Below we offer a summary of the action across these periods…

2004 carried over the 2003 growth momentum: The year 2004 began at a 1.0% fed funds target at a point in time when the US economy was over two years into an expansion (from Nov 2001). The five fed funds hikes saw a delta of +125 bps in 2004 to 2.25%. That 1% starting point in 2004 came on the heels of a GDP growth rate of +6.8% in 3Q03 and 4.7% in 4Q03 (2Q03 was +3.6%). The PCE lines were strong and Residential investment was soaring in the GDP accounts in 2003 and 2004.

The 3% range GDP growth numbers might sound low, but for context neither Trump nor Obama ever hit a 3% handle number on an annual basis. We have looked at some of these numbers before, and the main theme is the post-2000 world is slower growth for the US. Using 4.0% as the line, Clinton made that level five times, Reagan four times, and even Carter did it twice (in only one Presidential term). Clinton did four years in a row at a 4% handle GDP growth in his second term. GW Bush hit 3.9% once in a near miss. Obama’s top year was 2.7%, which he did twice over two terms. Trump’s top print was 2.9% in 2018 after a record tax cut. Biden hit 5.7% annual in 2021 on the COVID rebound. The 2022 annual number is expected to be positive with a 1% handle, but that is not a lock yet.

The fact that the Fed tightened from 2004 through 2006 was quite understandable, but the all-in rates on the curve made aggressive leveraging very tempting. Credit fundamentals were very strong for lenders. During 2004, inflation was modest but rising. The CPI line exited 2003 at 2.0% in December. CPI trends in 1H04 were mostly 1% and 2% handles for 5 months and then 3% handles posted in the last three months of 2004.

2005 as the peak housing year: Fed funds started 2005 at 2.25% with the year showing the heaviest slate of tightening actions across the three years. The series of hikes during 2005 totaled 200 bps to a 2005 exit rate of 4.25%. The GDP growth rates in slowed from 2004 with 2005 quarterly GDP growth rates moving from 4.5% in 1Q05 to 2.3% in 4Q05. The market even saw residential investment turn slightly negative as 2005 marked the homebuilding peak. Residential investment growth started at 9.8% in 1Q05 and notched down across the year to -0.8% in 4Q05. Residential investment turned deeply negative in 2006 and worsened materially in 2007.

CPI was also ticking higher across 2005 with two 4% handle months and six 3% handle months in contrast to the two 1% handle months, six 2% handle month, and four 3% handles in 2004 (including each month of 4Q04 at 3% range. CPI exited 2005 at 3.3% CPI but moved around a bit with two 4% months, three 2% months, and seven 3% months (including 3% handles in last two months of 2005).

2006 starts strong but quickly falters: Greenspan retired in January 2006 in what was shaping up as a challenging year. Inflation ticked higher to 4% handles in May, June and July but tailed off sharply from Sept to Dec 2006. The market saw a UST inversion by the end of 2006 as detailed in the UST chart above. That is a typical flag for cyclical risk, and there was plenty of risk on the other side of those yield curves. We saw 100 bps of tightening by the Fed – all in the first half of 2006 – and fed funds crossed the 5% line to 5.25%. The market saw a more mixed picture out along the curve with the intermediate to 10Y segment of the curve moving in a much tighter range.

The year started hot on a solid PCE line that drove a 5.5% 1Q06 GDP growth. The Gross Private Domestic Investment line saw three quarters of contraction, however, after being positive in 1Q06. The Residential investment line turned deeply negative after the 2005 peak. The 3Q06 quarter in the summer peak housing season saw -20.4% in Residential investment and that line was down to -29.3% by 4Q07 the following year.

The market in 2022 is starting to see that scale of negative numbers in Residential as I covered to end last week (see 3Q22 GDP: It's the Big Little Things). The 2006 numbers also showed a sharp decline across the Nonresidential investment line from 1Q06 to 4Q06 but still positive. Structures and Equipment weakened, but Intellectual Property investment stayed strong and trended favorably. In 2022, we are seeing weakness in Nonresidential structures in 3Q22 that are off sharply at-15.3% and Residential at -26.4%. The good news in 3Q22 is Equipment was +10.8%.

The PCE GDP line coming out of 2006 started to flag as the calendar turned over into 2007. GDP quarters saw two 1% handle PCE lines, but GPDI was negative for 3 of 4 quarters in GDP. The annual GDP growth in 2006 and 2007 had 2% handles. Dec 2007 was later tagged by the NBER as the business cycle peak and the start of the recession as the markets headed into the crisis year of 2008.

Mortgages: low rates, bad underwriting, reckless borrowing, too much systemic leverage

A period as complex as 2004 to 2006 is hard to summarize, but the above subtitle about sizes it up. The “daisy chain” of bad behavior is not new. The concept of “counterparty risk” is more arcane than a bad asset with high volatility and a price downside of zero (in theory). The market is more accustomed to that in debt and equity. The exercise of pricing downside is usually more about a stand-alone issuer. Evaluating loss exposure from one issuer is a feature the market has more familiarity with for both good or bad reasons. Measuring counterparty risk and the layers of loss handicapping from counterparty default to collateral price risk is tricky.

The approach to disclosing such risks is also a big bucket of worms that is harder to grasp. The challenge in quantifying the risk exposure and assessing the range of outcomes can set off widespread risk aversion in an illiquid market if investors lose confidence. That was happening in extreme fashion after the hedge funds started to blow up in late 2007.

The start of the crisis revolving around a few major institutions…

I will be looking at this counterparty and disclosure topic in other notes, but the essence of the systemic crisis that unfolded in 2008 was tied to bank interconnectedness and the fear that “domino risk” would unfold. Domino risk scenarios kick in to the extreme when hedges on market risk turn into credit risk and when the counterparty who owes you on the trade puts the “No Fish Today” sign up.

As a specific disclosure example, no one in the public domain knew that the fate of the US and European bank system turned on AIG counterparty risk. When the exposure lists were published there was more than a little shock. There is a reason AIG got the support and Lehman did not. The Lehman risk was bad enough.

That cascading counterparty risk more broadly cuts across mortgage derivatives, CDS, rates hedges, currency hedges, etc. If an AIG collapse took out some major banks, the fuse is lit yet again on all of their contractual commitments as liquidity fears start hammering other banks. That includes lending commitments as we saw when Lehman dropped from bank lines where they had obligations to provide funding to others. The fear back then was those failed commitments would create more defaults and defensive drawdowns on a much larger scale than we saw in COVID. Then the liquidity panic escalates. That backup line and liquidity fear was also evident in the commercial paper market with backup lines for brokers.

The old song of “Wall Street vs. Main Street” lacks depth and conceptual grasp…

The view of many (including me) is that AIG would have been “game over” if the usual “let the market work” ideology was embraced. The “bail out Wall Street instead of Main Street” chatter forgets that Main Street is a hostage to the fate of Wall Street across so many areas of finance, liquidity, and asset valuation. The “Wall Street vs. Main Street” plays well politically but reflects either ignorance or an easy spin for the constituencies. If you need to be impolite (a common political and Wall Street habit), then just call Main Street a human shield. Then try to figure out what happens to Main Street with an impaired Wall Street. We got the longest US recession since the Depression after 2009 with a bailout! Congress tends to skip the layered analysis unless the support staff can get it on an index card.

The counterparty chain reaction breakdown happens when cash securities face margin calls, derivative gross exposure breaks down, OTC liquidity collapses, and the marshmallow guy from Ghostbusters shows up. Those are extreme and remote outcomes that were avoided by prudent regulatory and legislative action and the ensuing reforms. Revisionists can argue about it after the fact, but GW Bush was not going to take the fall on that. Neither was Obama. It was reminiscent of Clinton/Rubin bailing out Mexico in 1995 after Congress said “No.” A Mexico default might have set off a contagion and taken down at lest one major broker-dealer.

RMBS roulette and the turbocharging of low rates…

The mortgage loans getting printed and rolled into RMBS (subprime or otherwise) is a detailed and convoluted story unto itself. The “quality” range of the loans originated, and the diversity of the products and rates charged (variable to fixed) have seen a lot written since the crisis. The low funding costs for mortgage lenders gave a lot of leeway to print fees, sell to packagers, and sometimes innovate all-new products (subprime RMBS and variants). That “excess credit” rule and bubbles applies. It is important not to abuse the bubble term, but it applied here.

The trends in products and distribution channels served to attract many of the wrong kind of borrowers and the wrong kind of originators and sales practices. The teaser rates and ARM products or various “Alts” (i.e., Alternatives to the usual long term fixed rate conventional mortgages) were at the core of what sent the market and borrowers over a cliff. For stockholders and bondholders, the related disclosure rules of borrowers and lenders were weak to nonexistent on these exposures. The market was sending signals as more of the mortgages were stamped “return to sender” by underwriters.

That 1% starting rate on fed funds in 2004 sent volumes soaring, new business units (mortgage bank subsidiaries, etc.) were established to capture the full value chain. Technology was the turbocharger. That later led to a lot of later finger-pointing at the originators, the “securitizers,” the rating agencies, the GSEs, and the borrowers. In the end, the actions and reactions made it a mess politically and legally.

The subprime RMBS modeling shortfall made mortgage banks, underwriters, and rating agencies a lot of money. The questions around how such products get launched is a laundry list of topics that can be broken into a lot of separate pieces. Among the more notable headline grabbers in the RMBS crisis was “liar loans” (false income, etc.) that were packaged and sold to investors. Many of us from that period have anecdotes and stories of someone making $50K and stating $500K as income. It still boggles the mind how that happens. Cold calls to “please take a 125% LTV mortgage loan” were part of the story lines of the time.

Liar loans as a microcosm…

The infamous “liar loans” and subprime RMBS captured most of the press, but that is not the main event. “Liar loans” are part of an understandable pattern of cause-and-effect and offer a microcosm of the bigger chain reactions. It takes a liar (the borrower) and someone (or daisy chain of “someones” and entities) who does not care if the borrower is lying (i.e., those who can profit and pass on the risk). Consumers get money, fees get generated, people default, securities owners lose money, lawyers make money, politicians make speeches, regulators get yelled at, and regulators yell at others.

The process is not rocket science – even if the RMBS and structured credit math and mortgage derivative analysis might be. The part where state and Federal budgets get supported by the dubious chain of behavior usually gets left out of the discussion, and the political outrage comes with an asterisk (the state, city, and the Feds don’t give back the sales tax, capital gains tax, income tax, or special interest political contributions). Homebuilding is a major multiplier effect industry. The related benefits were huge ahead of the later retrenchment. Economic activity and winnings get generated, but the “due bill” comes later.

Even with the story around liar loans, the bulk of the problem still was the honest loan at very excessive loan-to-value cash proceeds that used structures that were doomed. The chain reaction would lead to household debt service stress as mortgage debt and RMBS structures built in assumptions of sustained home price appreciation and assumed traditional correlations in relationships across regions. Resets on variable rates in a bear flattener did not help either. High correlation across every region was not the game plan in the RMBS models, which used old data to do their incantations.

Snapbacks in rates and declining home values tripped the wire as the market blew up. As usual, that created value opportunities as in most liquidity-constrained, high-risk markets when things go terribly wrong. I will be looking in more detail at housing sector histories and compare-and-contrasts with today’s housing markets in separate notes.

To summarize, the subprime RMBS structured credit deals ran wild, inventions such as CPDOs leave room for an insanity plea, and counterparty exposure grew exponentially (theoretical maximum potential exposures or otherwise). Private equity firms drove record LBO volume, and leveraged loans went mainstream as a major asset class. Commercial real estate leveraging spiked alongside the RMBS binge. Wild times. The post-TMT cycle years marked the last cyclical ride for some major brokers and the banks. That means the times were “way too wild.”

A note on the title “Last Hurrah”

I picked the title “Last Hurrah” for this piece since Greenspan retired in January 2006 after a long stretch in the seat from August 1987. That was a very long timeline, and his service was during a period of extraordinary change in the capital markets and regulatory structure as banks poured in capital across the 1990s.

The picture above shows the movie of the same name, the Last Hurrah (Spencer Tracy, John Ford film). The back story on “The Last Hurrah” picture (from a bestseller novel) revolved around an aging Boston Irish machine politician (clearly based on James Michael Curley) who was benignly corrupt (but nothing on NY Tammany scale). You can get arguments from the ghosts of the old Boston Irish that there was no corruption or a rebuttal from reformers and old school Boston Brahmins (represented by Basil Rathbone of course) that Curley was anything but benign. Since “his people” got my Great Grandmother a job at Carson Beach (South Boston) during the Great Depression, I vote with the ghosts.

On a belabored side note, when I was growing up from school age through high school, there were two framed portraits on the wall in my little workspace: James Michael Curley and Chesty Puller. One of them was of a deal-cutting “pol” working the smoke-filled rooms (Curley). The other (Puller) is a Marine icon who is all about charging up the hill and getting it done. We suspect that Greenspan was more a Chesty Puller than a Curley in his approach to the job, but I suspect he wished that he did not charge up that hill after the TMT equity market sell-off from 2001 to 2004 and leave fed funds at 1% into 2004.

Greenspan’s conviction was there behind his monetary policy, and his commitment to manage his mandate was clear during his Last Hurrah years. But it was the second down-cycle in a row where he went over the top (or into the basement) in easing fed funds. A price was paid in the follow-through that saw the housing bubble and leveraging binge. NBER says the recession ended in Nov 2001 for an 8-month recession (Mar 2001 to Nov 2001), so being at 1% in 2004 hangs in the air as a question. The short recession mirrored the 8 months in the July 1990 to Mar 1991 recession. Greenspan ran low fed funds and a steep curve into overtime in both.

What comes next in a Powell Last Hurrah?

The Last Hurrah title might apply in this next round of Fed actions in coming months. Whether it will be Powell’s last term is speculation, but the question is whether he will trade off high market volatility and high recession risk for slower easing, softer language, and calmer nerves in the markets and in Washington with an absolutely brutal election ahead in 2024. The market will hear him out the next two months and see if he is Curley or Chesty or a creative combination.

The November meeting kicks off this week but that will be more about language and tone. The December meeting will be more about “the number.” The flip side is he can stay the course and break inflation with no stone unturned. That would be a Volcker move. Paul Volcker was probably more like Ajax from the Iliad and a blunt instrument kind of guy more than a Chesty Puller type. Despite saluting James Michael Curley’s beautiful home in Jamaica Plain every time we drove by when I was a kid, he was not quite Federal Reserve material.