Misery Index: The Tracks of My Fears

We look across the decades at the Misery Index (Inflation + Unemployment) with June 1980 at 22% showing real pain.

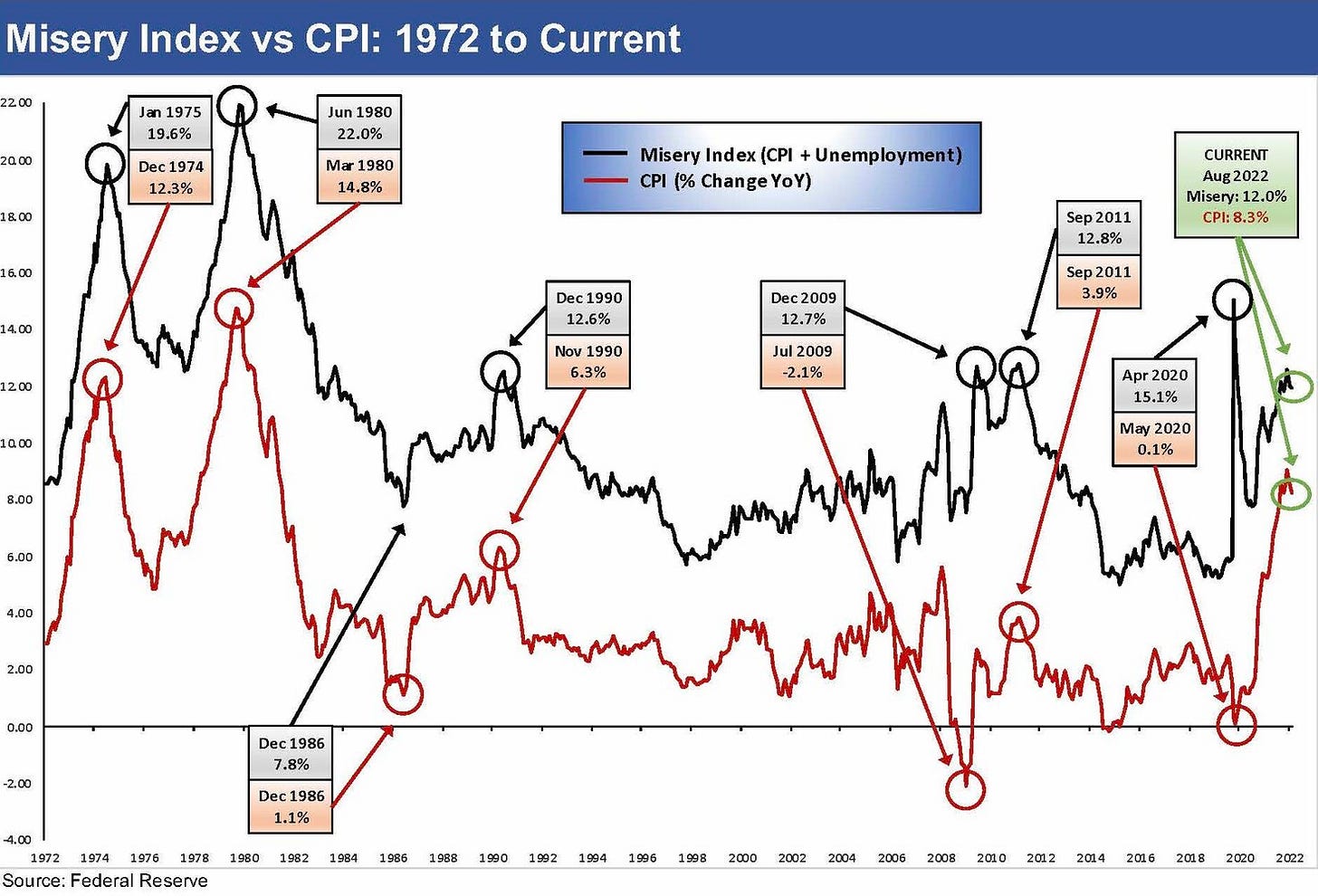

The attached chart tracks the Misery Index (inflation + unemployment) from the stagflation years of the 1970s to 2022. In the context of today, it is good to remember how bad it can get and consider what was different in the previous stagflation markets as well. The timeline in the chart runs across the 22% Misery Index of June 1980 (my date of arrival in NYC for my first job), and that ugly peak is a very long way from the current 12% level. We saw 12% handle misery indexes in 1990, 2009, and 2011, but the very brief spike to 15.1% in April 2020 came with an asterisk of temporary COVID shutdowns.

With that history, it is not hard to see a scenario where the index gets back into the mid-teens subject to how the yield curve and global turmoil affect the US employment picture in 2023. There is a reason UST volatility has been so wild of late since inflation will drive the Fed, and relief further out the yield curve is in no way a sure thing with rates below CPI and PCE. The two negative quarters of GDP and a rough winter ahead for global growth facing a strong dollar are all adding up to a wide range of potential outcomes. Corporate earnings will weaken on a forward run rate while unemployment has symmetry that makes it easier to expect higher jobless rates. Whether that will make for eased inflation fears broadly or diminished pricing power for labor and goods and services providers is no layup. Cost recovery in pricing flowed through to customers will get tested by industry. That will be a hot topic in 3Q22 earnings season.

The Misery Index (CPI + Unemployment) was coined by the famed economist Arthur Okun back in the 1960s. Since he worked for President Johnson as Chair of the Council of Economic Advisers at the peak of the Vietnam War, the inflation connection is a direct one. The year 1965 (when the Marines first landed in Vietnam) was the last 1% handle annual CPI year until 1986. The CPI lift thus began in the late 1960s even before Arab Oil Embargo of Oct 1973. We already looked at an event timeline from 1965 across these decades in a recently published commentary (See Inflation: Events 'R' Us Timeline 10/6/22), so for this note I just highlight a few key takeaways from the path of the Misery Index from 1972 to 2022. In the chart, we highlight periodic peaks in the Misery Index in the small boxes with recent CPI peaks also noted in the lower part of the boxes.

Key Takeaways

The 1970s and 1980-1981 stagflation years were in a world of their own: Unemployment rates in the 9% to 10% area are rare enough, but cycles seeing that sort of household jobs pain during times of high inflation has so far been concentrated in those two periods – the Nov 1973-Mar 1975 recession and the 1980-1982 double dip. The question today is whether we can get anywhere near that level again. After the COVID employment crunch of April 2020 and systemic crisis of 2008, it is hard to get past the higher bar that has been set for what were supposed to be six standard deviation events. The 100-year flood timeline has gotten very compressed. The new/old rule is “never say never.” The fact that we have seen these levels before makes life easier for the more extreme bears (I am not one of them). As we look ahead, the profile of jobs in the services economy has more room to allow for structural underemployment than double-digit unemployment in 2023 even though we got to 10% in 2009 as a lagging effect of the credit crisis. The reality is that there is a path for the Misery Index to move higher in 2023, but a lot needs to go wrong in the business cycle as well as in the line items of inflation, especially in housing, food, and healthcare. If we look back at the stagflation years, the breadth of inflation pressure ran well beyond energy pricing.

Oil and natural gas bring infectious fears from the “old days”: During the Arab Oil Embargo of 4Q73/1Q74 and the Iranian oil crisis of 1979, the US was essentially and effectively dependent on OPEC supplies. The term “lack of energy independence” meant something in those days, and it is getting misused these days. More recently, discussions on “import dependence” often fail to put in proper context the “who” part of the importing nations story vs. the bad old days of 1973 and 1979. By the mid/late 1970s, the US was getting around 85% of its crude oil from OPEC. During 2021, that OPEC share was closer to 13% (source EIA). As an exporter of crude oil into the US, Canada is now the Big Dog (a G7 Dog that is politically stable, geographically connected to the US, and part of a free trade agreement with the US), accounting for over 60% of the US crude imports in 2021. The US was in fact a net exporter of “petroleum products” but a manageable net importer (imports – exports) of just crude oil. There are a lot of crude oil, NGL, refined products and LNG statistics to look at (for a separate commentary), but the bottom line is that the US is in a much different position than during the stagflation years. Basically, the national security aspects of crude oil for the US today have negligible resemblance to 1973 and 1979. That said, it remains a major problem for many countries, and that keeps the heat on global energy prices. The biggest challenge will remain the line being drawn on climate issues vs. energy security and how to strike a balance.

The single biggest difference today vs. the stagflation years is US supply: In the years after the Arab Oil Embargo, the North Sea, Alaska, and Mexico ramped up by the early 1980s into a production boom that saw OPEC fight for market share (contributing to the 1986 oil collapse). In today’s markets, Canada is a major factor in the oil markets, and that was not the case back in the stagflation years. It ranks No. 3 in the world in total reserves. The current political spin around US energy dependence today is grossly misleading since the US has been consistently hanging around No. 1 among the Top 3 crude oil producers since the shale boom (with the Saudis and Russia) and is by far No. 1 now in liquid hydrocarbons. The US has the second largest field in the world in the Permian, which by itself produces more than most OPEC nations. The US is a major exporter of oil, petroleum products, NGLs, and LNG. As far as imported oil dependence, Canada dwarfs all of OPEC combined several times over as an exporter to the US. Keystone pipeline politics prevented that Canadian share from going higher. Politically stable and democratic nations that are in the NORAD chain of command do not qualify as national security risks. On a side note, NORAD is disturbingly topical again of late. The pipeline capacity obstacles and political opposition to pipelines in the US and Canada is the main supply constraint to further whittle down OPEC’s share. The Canadian oil markets also depend on the US market given the limited tidewater access. That is all a significant structural risk difference for “now vs. then.”

The 1990 Misery Index spike is tied in part to the first “Iraq War”: The jump in the Misery Index in 1990 was part recession reality (jobs) and part oil spike after Iraq invaded Kuwait in August. Desert Storm deadlines loomed ahead of January 1991 in a time long before the shale revolution. That was in the days when oil would spike just on harsh language anywhere near the Gulf. Oil plunged quickly as soon as the bombing started, and Iraq was rolled back with its military occupation quickly dispatched. In the US, the recovery soon began with a lot of Fed support well into the expansion period, and the misery receded. The oil markets saw more crashes than spikes in the 1980s and 1990s until the 2003 Iraq war brought some sustained upward oil price pressure.

The 2009 and 2011 Misery Index peak was about unemployment: The year 2008 was chaotic and brutal and by 4Q08 was amplified across the multiplier effects of the economy, but we did see a record high nominal price for oil in the summer. That only briefly took CPI to a 5% handle in the summer before the crisis sent CPI back into the negative zone in 2009 on the crisis aftereffects. Strangely enough, right up to the August 2008 FOMC meeting, some FOMC members were still flagging inflation as the main threat. Lehman was a few weeks later. As with the April 2020 COVID spike, the jobless problem was the main event after the credit crisis as the recession troughed in June 2009. As brutal as the credit crisis period was on the economy (a post-Great Depression record length of 18 months), the silver lining news was the stabilizing mechanism of weak commodity demand and a consumer sector that helped mitigate any wage-price inflation threat. Global commodities were resilient enough on a booming China after the credit crisis, but the US had employment headwinds that lasted for several years into the expansion.

Lessons for today on the Misery Index: In today’s market, the question revolves around whether the stabilizing mechanism of demand destruction will come into play in the commodity markets and influence the wage picture also. Questions around the much discussed (and poorly defined) inflation expectations X-factor will see more airtime, but we still expect the monthly focus on CPI (headline and core) will be the main exercise for the markets. We have another one this coming week, and the deep-recession bears and soft-landing bulls will make their cases. Earnings season is dead ahead and the market will be grasping for signals on where and when and in what industries pricing power might hit headwinds. With Europe poised for a deep recession in the eyes of many (including me) and a very troubling winter ahead, China presenting a mixed picture, and more than a few variables (notably jobs) still in handicapping mode, the fall season will not resolve the US issues even if it sends signals. The direction of corporate revenue and earnings will be crucial as post-3Q22 guidance season rolls in. We still expect relative resilience in US employment, and we note that there is ample room for modest erosion without letting extrapolation run amok into deep recession forecast. We see more inflation worries given the mix of factors and fresh debates on the terminal fed funds rate. The Fed is facing a lot of criticism for a late start, and the empirical evidence now is that “late” is being kind.

Will fed funds vs. CPI normalize in line with past histories?: The Fed still has a lot on its plate with target fed funds and inflation still showing divergence from past trends. The relationship of CPI and PCE vs. the fed funds rate is out of alignment relative to pre-crisis cycles (i.e., before 2008) and should be above inflation if history holds. A target fed funds rate of 3.25% and CPI of over 8% are set against a 35-year median from 1972 to 2007 where fed funds was over 2 points above CPI. For the full-time horizon from 1972 until today, the median differential of fed funds and CPI was that fed funds was .5 point higher. The credit crisis and COVID has distorted the relationship with CPI above fed funds by 1.1 point (i.e., fed funds minus CPI= -1.1) during the bank system bailouts and ZIRP/QE relief focus. Were they doing something wrong in the decades before the crisis? Or will it now revert? In a case of piling on, the Fed’s balance sheet downsizing will also bring a lot of scenario-spinning around its effects on expansion plans across industries or in stock valuations. If the UST sees more upward shifts (even if not steepening), duration will feel more pain.

It will be interesting to see if the Misery Index makes a comeback as a term to use in a midterm election year. So far that is not the case. Inflation is the much better sales pitch for the GOP and employment is better for the Democrats. Adding those two together is less compelling for the GOP. Romney took a shot at the “Obama Misery Index” in his run in 2012, but it did not catch on. Inflation has not been a juicy political topic since the early 1980s. It hurt Ford and crushed Carter. Reagan had to deal with the pain of the 1982 midterms and Volcker as a force to be reckoned with, but then the bull market was on after 1982. The Misery Index might be more a topic for 2024 if Russia-Ukraine, China-Taiwan, higher US rates, and a strong dollar play out the wrong way.