Greenspan’s First Cyclical Ride: 1987-1992

We look at Greenspan’s policy moves in the 1990 recession. The focus on bank pressure took the helm into the expansion.

Summary

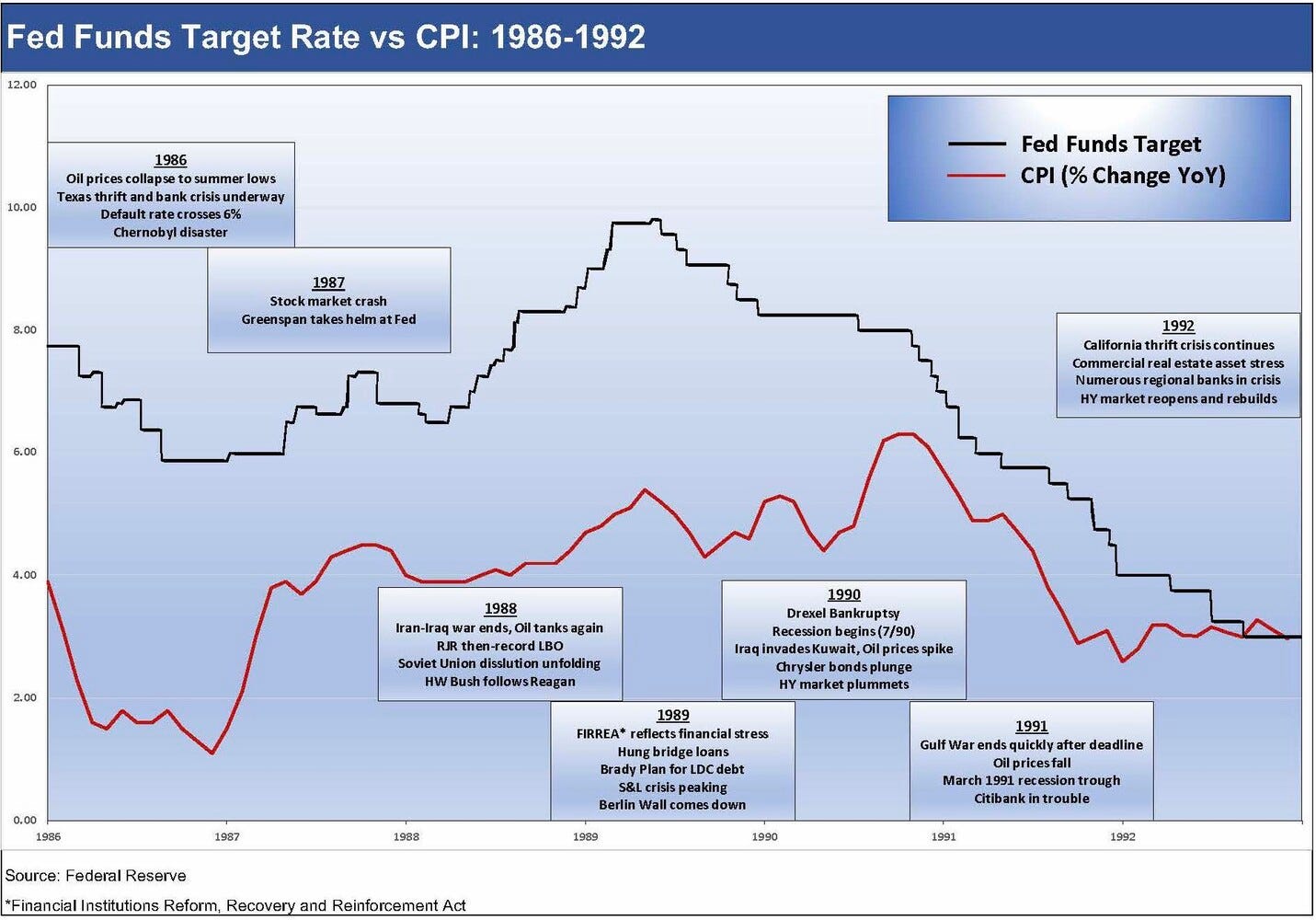

As everyone gets locked in on what the Fed might do in Dec 2022 and into the new year, we look back at the late 1980s, which was another period where the Fed’s intensive inflation focus was on display. We are beating the theme to death that the Fed has typically run fed funds above CPI (as a side effect or otherwise), and the late 1980s boom offers yet another example.

This very strong period of growth and risk-taking came to an end after a material tightening process across 1988-1989 that saw the credit cycle come to a screeching halt even as equities performed quite well. The business cycle was not tagged by NBER as peaking until March 1991.

From my vantage point, the fed funds vs. CPI relationship at the end of the 1980s boom is one more major data point for the pile that says the Fed in 2022 is still not quite in full arsenal mode. If inflation does not move, past examples will be held up as signs that they have a long way to go.

In this commentary we look back at the fed funds (“FF”) rate vs. CPI (“FF-CPI”) just as we did in earlier pieces on 1990 to 2007 (see Fed Funds, CPI and the Stairway the Where?) and in our review of long-term FF-CPI differentials (see Fed Funds-CPI Differentials: Reversion Time?). We also plot the UST migration of the period from year end 1987 shortly after the stock market crash of Oct 1987 through the 1988 and 1989 experience and then through the 1991-1992 steep curve periods. The late 1980s saw smoking hot credit markets hit a deep freeze in 1989 that was mirrored in a cascading set of problems in banking and brokerage sectors. Some of these setbacks ran for years (notably commercial real estate) and made fed policy actions even more focused on broader financial stability rather than just its dual mandate.

What makes this current period in 2022 much tougher for the Fed is that the global economy is a mess, the US economy is at best in stagnation mode and inflation is very high. In the summer of 1989, CPI did dance around 5% handle, but the 1988 and 1989 months were mostly seeing 4% handle CPI numbers. That was after 1987 started at a 1% handle and exited the year at 4.3%. That pattern is captured in the charts above.

Demand also was quite strong in those market even with fed funds running well north of CPI. The year 1988 put up +4.4% annual GDP growth with +5.4% in 2Q88 and +5.4% in 4Q88. The threat to the economy around the Fed tinkering with those growth rates was a lot less risky than today.

With the early 1980s pain still very much in the minds of the Fed and the market (and with the Reagan administration soon to pass over to George HW Bush in early 1989), low inflation and solid growth was a relatively common goal even if pure inflation hawks and balanced budget advocates were all about fiscal and monetary prudence.

Key takeaways from the 1987-1989 experience

Inflation remained a fixation: The differentials in fed funds vs. CPI were especially noteworthy in the late 1980s and present a dramatic contrast with what we see in 2022. The Fed’s policies did not stall the 1980s boom in stocks, the economic expansion, or the soaring growth in corporate bonds that came with the steady disintermediation of the banks in debt markets. The Reagan economy was very strong and the functioning of the White House and Democratic held Congress was very successful (even with the battles to get there and even if sometimes it seemed nasty at the time). The same was true in the 1990s with Clinton after the “Republican Revolution” of 1994 in Congress (despite the shutdown moment, which voters frowned upon).

In today’s world, Reagan would be called a RINO by the right and Tip O’Neill a right-wing Hun by the left. Political fights used to be so much more fun and less damaging in the 1980s and 1990s.

A big challenge in 2022 is striking the tough deals with the polar forces undermining centrist solutions in the interest of “the base.” Pick an inflation battle and try to frame some solutions (e.g., pipelines for supply). These gaps cannot be narrowed given perceived IOUs. The political (thus fiscal) backdrop hinders the inflation. That basically leave the Fed and its monetary tools as the main means to fight inflation.

The infrastructure bill was almost derailed since it might be perceived as a win for Biden. Was it inflationary? Yes. All demand increases are inflationary when supply chains are a mess. Will it make soft landing more likely? Yes. Why? Since the infrastructure bill and the later IRA entails a multiyear process that cuts across many states and sets the table for investment. That means revenue for companies and jobs for people.

In the rail earnings and some recent economic data releases, we see numbers that translate into tonnage for the freight companies, but with it comes pricing power. That is the tradeoff that makes life tough for the Fed. The 50-year low in unemployment and decent industrial production are good things. The only way to slow it down is with punishing interest rates that curtails demand (“demand destruction” is such an unpleasant term).

Starting the late 1980s with a forgotten stock market crash: The October 19, 1987 stock market crash is often forgotten in discussions of the later 1980s period when the focus was more on LBOs and the soaring bull market for equities. Sitting at my desk staring at my Quotron (yes, a Quotron) that day (“Black Monday”) was a bit surreal given the percentage decline (-22%), but the markets – and especially fixed income – got back to business fairly quickly. There was some minor action by the Fed, but the eyes remained on inflation at the FOMC. The Volcker years were still in the air even with the 1% handles on CPI from 1986.

Bring on the leverage, bring on the dealmakers: 1987-1988 was the period in the credit markets when the US HY bond boom and more aggressive capital structures were the norm. The “leveraging of corporate America” was a theme along the way as the bond markets saw rising disintermediation of the banks and much-enhanced demand from investors for new mutual fund products and evolving pension fund strategies. I was on the buy side at Prudential insurance at the time.

After being hired in private placements, the human traffic was heavy into the “public” capital markets unit where HY, IG, and money market investments were managed. Numerous executives from private placement groups eventually moved on to private equity firms (the head of private placements moved on to his own LBO firm with his name on the door, and others from that department went the private equity route). The money chase was on, and the markets were evolving rapidly.

Let the tightening begin: When the economy stayed hot in the later 1980s, the new guy on the block (Greenspan arrived Aug 1987) got busy quickly. Fed funds started 1987 at just under 6% and the Fed was tightening through spring to 6.75% before some waffling in the 6% handle area until tightening to 7% handles in the fall and then ending the year over 6.8%.

Then 1988 got back on the tightening track and fed funds moved from over 6.8% to just under 8.7%. The CPI level spent much of 1988 with 4% handles (10 of 12 months in the 4% range with 2 months in 3% range), and that was enough for the Fed to keep hiking.

Asset returns framed in a bull market with a higher yield curve: An interesting asset class feature in 1987 was that cash returns beat the major equity and fixed income benchmarks with a 6.7% return. The next time cash beat all equity and debt benchmarks was 2018. A 6% handle return on cash sounds pretty good in 2022, but in 1988 and 1989 equities were back on top by a large margin. The bull market run rate for annual returns across the 1980s-1990s were just under 18% per year for nominal total returns in the equity asset classes (Source: Wilshire, CalPERS). CPI averaged around 5.6% in the 1980s and 3.0% in the 1990s, so that was a very solid stretch for risky asset returns on a real basis after the negative real returns of the 1970s.

The Russell 2000 printed +22% returns to end 1988 at #1. The capital markets remained very bullish in 1988-1989 almost despite the realities unfolding in the economy and financial system. We saw variations of that same reality-equity return divergence in 1999 when the NASDAQ kept soaring in equities (+86% total return) as the credit market issuers in TMT were taking a beating and default rates were climbing. By 1989, the economy was starting a stall later in the year (0.8% 4Q89 GDP), but the final big year of the 1980s bull market in equities was put on the scoreboard at a 31.7% S&P 500 return in 1989.

The Fed hits brakes, reverses course in 1989: The above chart runs across the UST curve moves from the increasingly messy period of early 1989 with its mild inversion into a downward shift in the curve. The pace and pattern of the Fed hikes and cuts in 1989 and into 1990 are broken out in the chart at the top of this note. That migration came after steady Fed tightening across 1988 and into the spring of 1989 in a period that saw trends in the market that were decidedly worrisome as reflected in the shift lower along the curve.

By June 1989, the Fed was thus reversing course on fed funds and taking them lower. The easing continued into 1990 as fed funds were lower by almost 3% from May 1989 to the end of 1990. The subsequent tightening in 1989 had seen 9% handles through much of the year and a high of just over 9.8% in May 1989. With such a curve, senior secured bank loans in LBOs would be getting compensation that would be ahead of the long-term nominal returns on equities. Chasing deals was a way of life for banks and securities firms and private investors. That came to an end very quickly.

Deal pain and leverage realities weigh on the 1980s home stretch: The collapse of the UAL (United Airlines) LBO in October 1989 – set against the hung bridge loans already in the headlines – was pretty much the nail in the coffin for that cycle’s LBO binge. The deal would have died a cruel death in the 1990 oil spike anyway, and the Gulf war after Iraq invaded Kuwait was not great for travel planning. Airlines were devastated in the war/recession/oil spike. The UN deadline was mid-January 1991 for Iraq to “get out of Dodge” and leave Kuwait, but before that both Continental Airlines and Pan Am went bankrupt.

Pan Am soon liquidated and ceased to exist, setting off some radical realignments of assets, routes, and slots around the world as TWA was also in stress. TWA (the legacy Howard Hughes storyline etc.) and Pan Am were the iconic carriers of the industry. The other legacy carriers (American, Delta, United, US Airways) would face their own issues a decade later.

Credit Stress and default rates still the lagging indicator: HY defaults were high in 1986 in the 6% area, but defaults declined across 1987 from a high 5% range to a 3% and 4% range in 2H87. The default rate in 1988 held in at an average of 4% handles and dropped again in 1989 to 2% midyear before starting a climb through year end to around 4%. That came ahead of the lagging indicator that would arrive in 1990 and send defaults climbing sharply to just under 10% by year end. The default rate peak was 13% in June 1991. The HY market was already in a major rally by then.

1990 ride gets very bumpy: The year 1990 was all set deliver a lot of pain in the markets with a few major securities firms in bankruptcies/bailouts. We have covered more of the headline events in earlier notes (see UST Curve History: Credit Cycle Peaks and Expansion Checklist: Recoveries Lined Up by Height). Drexel filed early in the year, and that was a major blow to the US HY market. The broker stress and HY bond disarray shut the door on bridge loans and badly disrupted HY bond market making. The shifts in the UST curve sent compensation for loans lower and the default spike in HY bonds to double digits in 1991 was going to take some time to work through.

Fed hits the down elevator button in 1991: We covered the extreme reaction and Fed easing hyperextension in other recent notes, but the visual at the top of this note speaks for itself. The easing continued into 1990 as fed funds were lower by almost 300 bps from the spring of 1989 to the end of 1990. And only then did the serious easing kick into high gear.

The fed funds target rate started 1991 at 7.0% and ended 1991 at 4.0%. Since the expansion ended (per NBER) in March 1991, the easing was notable. The year 1992 started at 4.0% target and ended 1992 at 3.0%. That held until Feb 1994. That year 1994 was a milestone tightening year as we covered last week (see Bear Flattener: Today vs. 1994 and Aftermath). Another way to look at it is that the Fed was easing and held at a low rate 3 years into an expansion. At the very least, the policy was great for bank mergers.

Financial system stress lingered and so did the Fed: The result as evidenced in the chart is that the Fed was super aggressive in its easing given the array of stress points in the financial system as well as in the economy. The easing extended well beyond the official end of the recession even though the valuations in the securities markets were already rebounding sharply in risky credit and equities. The risky asset markets troughed in 1990, but the financial system hangover continued with the most notable victims being banks overexposed to commercial real estate (e.g., Bank of New England was seized in 1991).

The California thrifts were also taking a beating into 1991-1992 as “the thrift crisis without end” ran on. We saw high profile names such as CalFed and GlenFed making the headlines and consolidation and mergers were the ticket in that sector whether merging companies or buying branches from thrifts that faced regulatory seizure. The FIRREA law passed in summer 1989 (the name Financial Institutions Reform, Recovery, and Enforcement Act highlights the financial system state of affairs) saw the Office of Thrift Supervision stay aggressive with the Resolution Trust Corp seizures. The credit tightening that comes with activities such as those of the thrift and regional banks crises were another reason for the Fed to “stay easy.”

Asset returns still highlight forward-looking game plan: Despite all the problems in the financial system there were some silver linings. The rebound in the valuation of risk assets in 1991 was impressive with US HY the #3 performing asset class at over 39% total return behind the #1 NASDAQ at just under 57% and the #2 Russell 2000 at +43%. HY was coming out of a secondary liquidity vacuum with the de facto lockdown of numerous brokers and the slow rebuilding of HY market-making after the Chapter 11 of Drexel in 1990 and bailouts of some other major securities firms (Lehman, First Boston, Kidder).

OTC risky credit markets need market-makers and secondary liquidity. That was coming alive in 1991 and brokers started to rebuild HY business lines. The bounce in 1991 set the stage for the “Class of 1992” HY business line personnel expansion that brought the next round of intensifying competition in HY, including the rapid growth of DLJ as a HY powerhouse. Some firms looked like Drexel alumni clubs in banking and leveraged finance teams as their experience quotients were beefed up in HY.

We did not want to get lost in the weeds of the late 1980s and early 1990s...

We detail the backdrop for context, but the main purpose of this commentary was to flag the FF-CPI relationship again. The years from 1986 to 1992 covered an extraordinary array of conditions but that close watch on inflation stayed consistent and saw fed funds materially in excess of inflation. That pattern held just as it largely did when Volcker was at the helm.