US Corporate Debt % GDP: It’s All in the Mix

We plot systemic corporate debt vs. GDP across the cycles and highlight some pivotal events.

"Less debt, less 90s, more eye of newt. Not Gingrich."

With the US Public Sector Debt % GDP covered in our prior piece, we turn to the historical timeline on US Corporate Debt % GDP.

The rise in systemic corporate debt (corporate securities + loans) tells a story of more rational growth with a few side trips to excessively risky borrowing where the growth of debt materially outpaced the long-term upward trend line.

While Federal public debt % GDP quadrupled from the start of the bull market 1980s through recent times, corporate sector debt had not even doubled by the all-time highs during COVID and has declined materially since the mid-2020 peak.

In this commentary, we look back across the cycles at the trend line of rising systemic corporate debt (securities + loans) as a % of GDP across some very event-filled cycles. Corporate bonds have a complex history as does the growth of the loan market. The size of the corporate credit markets reflects extraordinary growth.

As we peel back the layers and add a slew of regulatory changes, the growth of structured credit and derivatives and more recently the explosive growth of private credit at the highest top down level, the balance of corporate credit rose sharply on the books of companies. In the context of the economy, however, corporate debt only doubled as a % of GDP over the same timeframe that public debt quadrupled. From the lows of the early 1980s (30% in 1981) to the highs of COVID (59% in 2Q20), we just missed doubling. That was before dipping down to the most recent reported level of 49% (see notes at the bottom for comments on the source material we use: the Fed’s Z.1 report).

We tried to detail many of the timeline events on the charts that we include in this piece, but below we summarize a small subset of key dates to capture the flavor of the big moves:

The 1980-1982 double dip recession: After the stagflation and ugliness of the 1970s, the 30% lows of 1981 and the end-of-recession 1982 level of 33% saw the 1980s bring startling growth in the absolute levels of corporate issuance. That supply saw plenty of demand as pension investment and mutual funds also saw breathtaking growth. Supply and demand for risky credit assets ran alongside a doubling of nominal GDP in the 1980s while the HY bond market was also born.

As the chart shows, the rapid growth of GDP still saw the systemic corporate leverage from the early 1980s level only rise to a recent 49% in 4Q22. That is a mild and measured rise all things considered and can still be held up to measuring sticks such as asset valuation and earnings (separate analysis). The due diligence checks of lenders was supposed to restrain the worst impulses of lenders and investors even if those checks on quality had some notable lapses along the way. Overall, systemic corporate debt is a very different beast than UST % GDP.

The 1989 credit cycle peak: We have covered credit cycles vs. economic cycles in other commentaries (see UST Curve History: Credit Cycle Peaks 10-12-22, Expansion Checklist: Recoveries Lined Up by Height10-10-22), and the 1980s was a case study in excess in some pockets of the credit markets (notably LBOs with frequent sub-1.0x interest coverages in new deals). 1989 was the credit cycle peak that started to unravel quickly in the second half with financial services companies under the gun (FIRREA legislation, thrift crisis, etc.) and securities firms experiencing a mix of hung bridge loans.

The takeoff in borrowing from the end of 1982 in the 4Q82 Z.1 data (Note: the recession ended 11/82) saw 10 points added on from the 33% in 4Q82 to 43% at the end of 1989. That is a 10 point move in a decade when GDP was soaring. The 10 point rise from the end of 1982 to the end of 1989 (only 7 years) broke above the trend line in a market where market making depth could not absorb the downside effects after such growth.

The post-1980s credit downturn and recession brought the level down: The hard landing had officially ended in March 2001, but Greenspan also had gone through his first of two mega-easing exercises. We covered those in earlier commentaries (see Greenspan’s First Cyclical Ride: 1987-1992 10-24-22, Greenspan’s Last Hurrah: His Wild Finish Before the Crisis 10-30-22). The reality is that Greenspan’s actions set the stage for a massive spike in borrowing in the 1990s and 2000s as bank lending/securities underwriting converged and non-US banks expanded aggressively in the US credit markets as well. As the TMT bubble underscored in the second half of the 1990s (see next chart), the credit quality and asset mix went in the wrong direction very quickly even as the Corp Debt % GDP climbed again.

We insert the post-1995 trend line in the chart above with the Corp Debt % GDP line plotted in a time series line but set that against a bar chart with the gross debt numbers from the Z.1. The bar chart sure makes a statement on the right side of the chart on the trillions piled on after the credit crisis. The hefty growth of the 1990s and pre-crisis 2000s pales vs. the dollar growth of the ZIRP and QE years.

The 1990s brings the next stage of deregulation and waves of new products and issuers: The steady phase-out of Glass-Steagall and rise of Section 20 bank subsidiaries in the bank family trees set off a competitive battle for market share across banks and brokers. By the end of 1999, Corp Debt % GDP was back up to 44% with a cloud over the quality of the mix after NASDAQ ended the year with a +86% total return. By that point, the B and CCC tiers were feeling the pain as the default cycle had already started and the equity and debt markets diverged.

As the chart above details, the 1990s had marked another sharp break from the long-term trend line in Corp Debt % GDP, and the results were similar in credit pricing pain and dislocated credit markets. The debt levels grew too rapidly, and the market could not manage the downside of so many bad deals. That in turn flowed into the longest (not highest) default cycle in history. The economic downturn was quite muted, but the credit cycle downturn was hideous.

2004 saw 1% fed funds (3 years into the recovery) and lit the fuse of excess: Systemic corporate leverage declined from 1999’s 44% to mid-2007 at 42%. The summer of 2007 was when the credit cycle hit the brakes and the housing crisis and counterparty risk took over. We also saw commercial real estate swept up in the structured credit boom (covered below). The relative abuse of the ABS rating standards (ABCP quality was a black hole of RMBS heavy SIV structures). This was when the world of counterparty risk and related exposure (not captured in corporate systemic debt line items) gave the world a wakeup call on the risks of bank system interconnectedness and high leverage in the shadow banking system. The word “dominos” was heard more than a few times.

The damage came from structured credit, RMBS, and CMBS and flowed into credit contraction broadly. The record LBOs were clearly a problem, but these were not the triggers. By Sept 2008, Corp Debt % GDP hit 45%, but that was not the main event. The interesting twist in the credit crisis of 2008-2009 is that the implode-a-thon was not caused by “systemic” excess in the corporate sector even if there were plenty of bad deals done. It was mortgages and derivatives driving severe credit contraction, feeding risk aversion, and badly impairing secondary market liquidity in the face of redemption risks.

Systemic corporate debt migrated lower and bounced higher after the 2008-2009 credit crisis: By Sept 2011 as the debt ceiling crisis was wrapped up in the summer, Corp Debt % GDP was down to 40%. Low UST rates across the curve and the world of ZIRP and periodic QE had added fuel to a trend of rising corporate leverage that has been in place since the 1980s. By the end of 2019, the Corp Debt % GDP was up to 48%, up 8% from the fall 2011 level. During the longest expansion in history after the crisis, long-dated and low coupon bonds became more like cheap equity for M&A and debt-funded buybacks. The BBB tier size really exploded across time as BBB debt climbed over 4-fold from 1992 to 2002 and over 4-fold again from 2008 to 2022.

The COVID exogenous shock: The wild period of COVID saw the government pour money into the economy and provide myriad shock absorbers across the corporate and household sectors. The Fed went back into ZIRP and QE mode including promises to backstop some corporate and ABS subsectors. A lot of bank lines were drawn down and two quarters in 2020 posted record GDP declines and record GDP increases in back-to-back quarters wrapped around the shortest recession in history. The short story is Corp Debt % GDP peaked at 59% at 2Q20 and then dropped back below 50% by the end of 2021. The ratio has been in a narrow 49%-50% range since 2Q21.

The chart above looks across the cycles at the relationship of total corporate liabilities (instead of total corporate debt) for a frame of reference. This time series includes more line items beyond total corporate debt and would include some with large balances that are also based heavily on estimates. The array of obligations (leases, pensions, OPEB, etc.) extend well beyond financial debt. The additional chart also offered an opportunity for us to add more events across market history in the boxes posted along the timeline chart.

The liability time series contrasts with the debt series in the line items chosen, and it is just another twist that adds on more of the right side of the balance sheet as a frame of reference. That is a lot of line items that show up with a range of underlying traits, pensions and OPEB and leases. It is another angle on the same general concept (“assets on the left, liabilities on the right”). The Corporate borrowers – like the US government – need to pay all their contractual commitments whether store leases, a defined pension benefits plan or Medicare and Social Security. Those liabilities are measurable under GAAP for corporations, but they do not get layered into the public balance sheet math. If they did, those numbers would be scary.

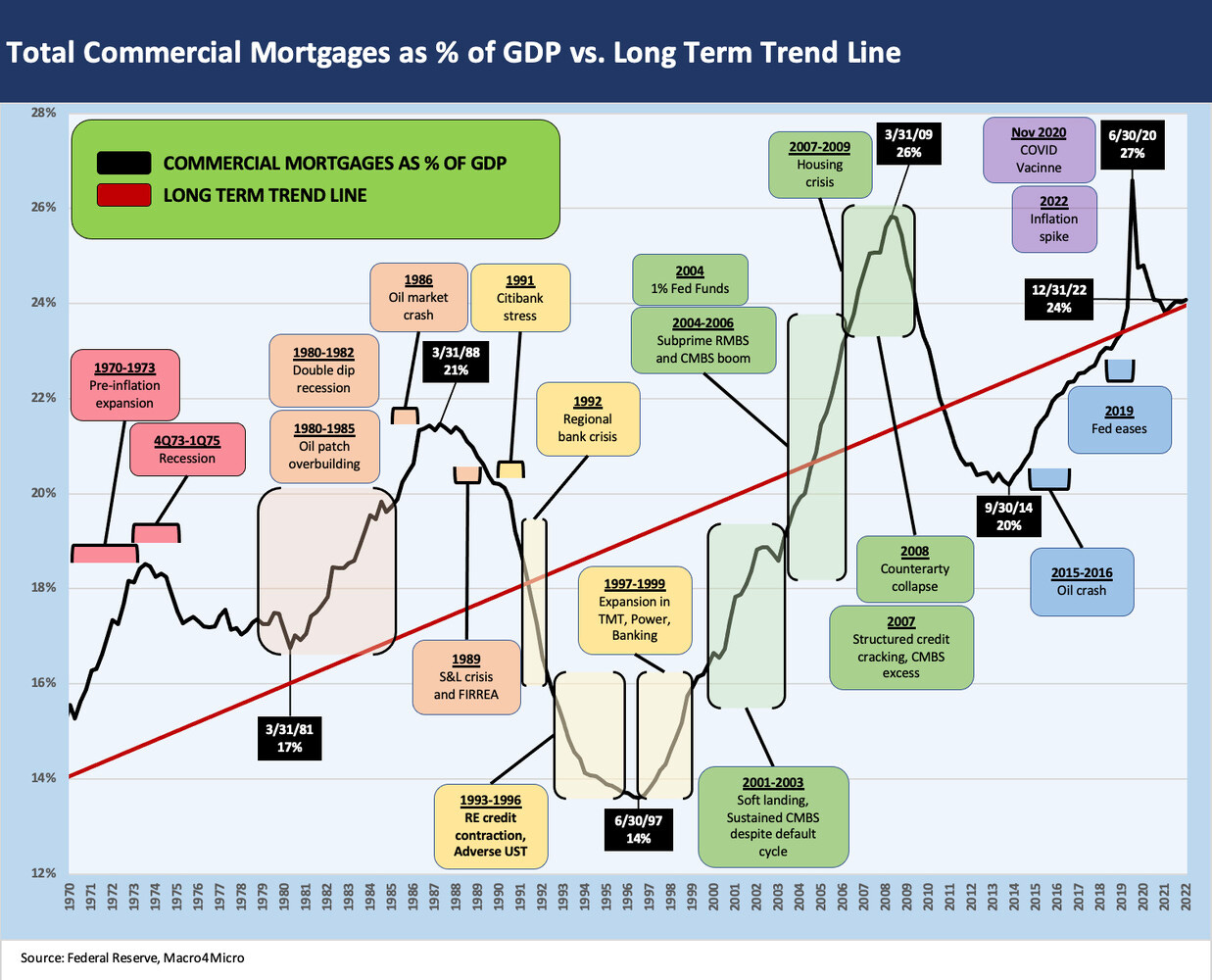

Commercial mortgage debt as a % GDP…

In the chart below, we plot Commercial Mortgages as a % GDP as an extension of the corporate sector leverage story although this comes with an asterisk that the line items below are the sum of “nonfinancial corporate mortgage liabilities + nonfinancial noncorporate liabilities.” The “noncorporate” mortgage liabilities of around $5.1 trillion and the corporate total of $1.2 trillion account for a critical sector (commercial real estate) that drives the financing activities in the US. Partnerships are major vehicles for financing in the world of real estate and fixed assets.

The above chart plots the history of Commercial Mortgage Debt % GDP. A few of the periods of excess and ensuing bubbles and blowups jump off the page even if the credit crisis period pales in comparison to what happened in residential (we will look at that in a separate Systemic Consumer Debt piece). The mortgage market has evolved dramatically across time from its traditional role with the commercial banks. The rise of securitization and structured credit made it easier to get financing and find funding as intermediaries pounced on the fee generation activities. Credit rating agencies were also along for the ride in this high-volume flow of investment grade rated products.

We drop the mortgage chart in the analysis as a frame of reference since so much of what goes on in real estate is commercial in nature and tied into corporate sector activities. We know that is a simplification given the array of real estate lending and residential targeted debt incurred by REITs and partnerships (e.g., apartments for residential). The activity is a big driver in the new construction markets or in the buying, selling, and refinancing of real estate assets. New building cuts across a wide range of categories (see Construction Spending: Demystifying Nonresidential Mix 5-9-23) and plenty of buckets of fixed asset investment (see Fixed Investment: Some Structure and Equipment Layers 5-12-23). Materials, machinery and equipment, freight and logistics, finance and more get wagged by the availability of commercial mortgage finance.

Some commercial mortgage events along the way…

The chart above shows the early 70s wave come to a screeching halt with the upheaval of late 1973 (oil embargo) that carried over into bouts of stagflation through the late 1970s and early 1980s. Then came the 1980 real estate boom from the oil patch (before 1986) to the explosive growth in the cities and services related infrastructure with banks and financial services near the top of the list in many cities. Bank aggression in lending and in later years, the rise of the CMBS markets all played a role.

The result of too much lending was trouble when economic growth did not last. There was an implosion in the Texas banks (among others) when oil and gas tanked and then numerous major cities in the East, West, and Midwest were in turmoil as the banking sector was hammered in the 1989-1992 period. Regional banks were crushed and more than a few were seized and merged into other banks along the way (Texas banks, Boston-based banks among some notable war stories).

Thrifts were another issue along the way from 1988 to 1994, and that means a lot of branches and a lot of headquarters as they rolled up into acquirers. 1989 was the S&L crisis peak, but that battle continued for years and especially in California. Some of those “bank and thrift branch consolidators” also blew up later in the credit crisis of 2008-2009 (e.g., Washington Mutual in Sept 2008).

The plot leading to the 2008 crisis in commercial mortgages has one layer after another, but the ability to overpay, overleverage, and pass on the credit risk led to bad behavior all around in all types of mortgages – commercial and residential. That sort of thing is now the stuff of legend, books, and movies. The ability to monetize real estate in leveraged transactions drove valuation too high whether as a pure real estate funding strategy or as part of leveraged M&A where the real estate could factor in how much to leverage the deal in a company being acquired (LBOs or otherwise).

Where the mortgage time series tied into today is that parallels of past mortgage meltdowns will be drawn – justified or otherwise – to regional banks of 2023 given their large commercial real estate exposure. We see the range of asset subsectors of today as very different than in the earlier cycles with some exceptions to ponder as we wade into 2023-2024 (see Construction Spending: Demystifying Nonresidential Mix 5-9-23). Sometimes the fears are justified, and sometimes credit contraction can make lurking problems worse in a hurry. Bank analysts and regulators will have their hands full.

Some background on the Z.1 report and systemic debt questions…

The above commentary updated a few of our old favorite charts from the Fed’s Z.1 report (“Financial Accounts of the United States”). The Z.1 is never light reading, and the most recent issue (posted in March) covers 4Q22 data. For those who have not had the recreational pleasure of hitting the print button on the Z.1, it is a quarterly statistical bible produced by the Federal Reserve that tracks a wide range of balance sheet data lines, flow of funds information, and various macro line items that help tell the story of the US appetite for leverage.

In this commentary, we looked at nonfinancial corporate leverage and commercial mortgages relative to GDP. As headlines speak of a debt-laden country, this corporate subset is an interesting vantage point on top-down debt metrics that directly impact what we follow in the loan and securities markets.

Corporate systemic debt offers some conceptual food for thought on the UST debt ceiling debates.

With the debt ceiling talks dominating discussions in recent days, these charts offer reminders of the simple fact that it is not just the dollar amount of debt but also the dollar amount framed against some yardstick for scale. When companies are growing assets, they can grow debt without a material change in financial risk if the quality mix is right. Gross debt levels can go higher if asset protection and cash flow are growing along with it. That is intuitive and easily demonstrated at the micro level for individual issuers. It also can play out in such empirical data points as bond index quality mix.

The consumer debt trends will be looked at in a separate piece, but the same general rules apply. Rising household debt needs to have some income increase (credit cards, auto debt/lease) or home valuation support (e.g., residential mortgages) or the risks are shifting higher as gross debt levels grow. Consumer debt also drives the PCE line of GDP and sets the table for fixed asset investment by corporations and governmental entities, Federal or State/Local (for the latter, don’t forget sales tax and property taxes, fees etc.).

In that fixed asset investment by corporations, a very big question over the years is “Where do they invest?” since the GDP line does not include plants in Mexico and JV investment in China. That only comes back through what gets sold in the US (to the extent the sellers are paying taxes in the US at all).

What is the significance of framing debt vs. GDP?

The Debt % GDP metric offers a timeline on the systemic debt levels vs. a broader economic yardstick. It is good to remember that there are many cauldrons of activity below that top line that you need to be aware of to avoid oversimplification. The same ratio can be filled with borrowers presenting high default risk or a mix that reflects solid quality, steady growth, and good economic news.

The old punchline of “When is enough too much?” is worth keeping in mind at the sector level (e.g., Corporates vs. Government). Someone makes a decision to borrow and lend, and the question of “Why” and “How much?” is where the real action is whether it is spending on EV infrastructure or defense weapons systems or buybacks and M&A.

Manufacturers can borrow to enhance shareholders or to enhance future growth prospects. They can borrow here in the US and then spend offshore. The list of questions to ask seems to never stop and the list of risk variables to frame is a very long one even with “easy credits” that influence overall asset allocation decisions. The exercise is why many of us worked in credit research. The variety never ends in industries and issuers and how the market prices it all.

While many will expect it all to be replaced by AI, the experiences over the years have shown it is easier to find “A” than “I” and the credit shocks underscore that. Some human with a fee target will overrule the AI decision and have bad inputs and a questionable set of assumptions for their output. Just ask the LTCM laureates.