Expansion Checklist: Recoveries Lined Up by Height

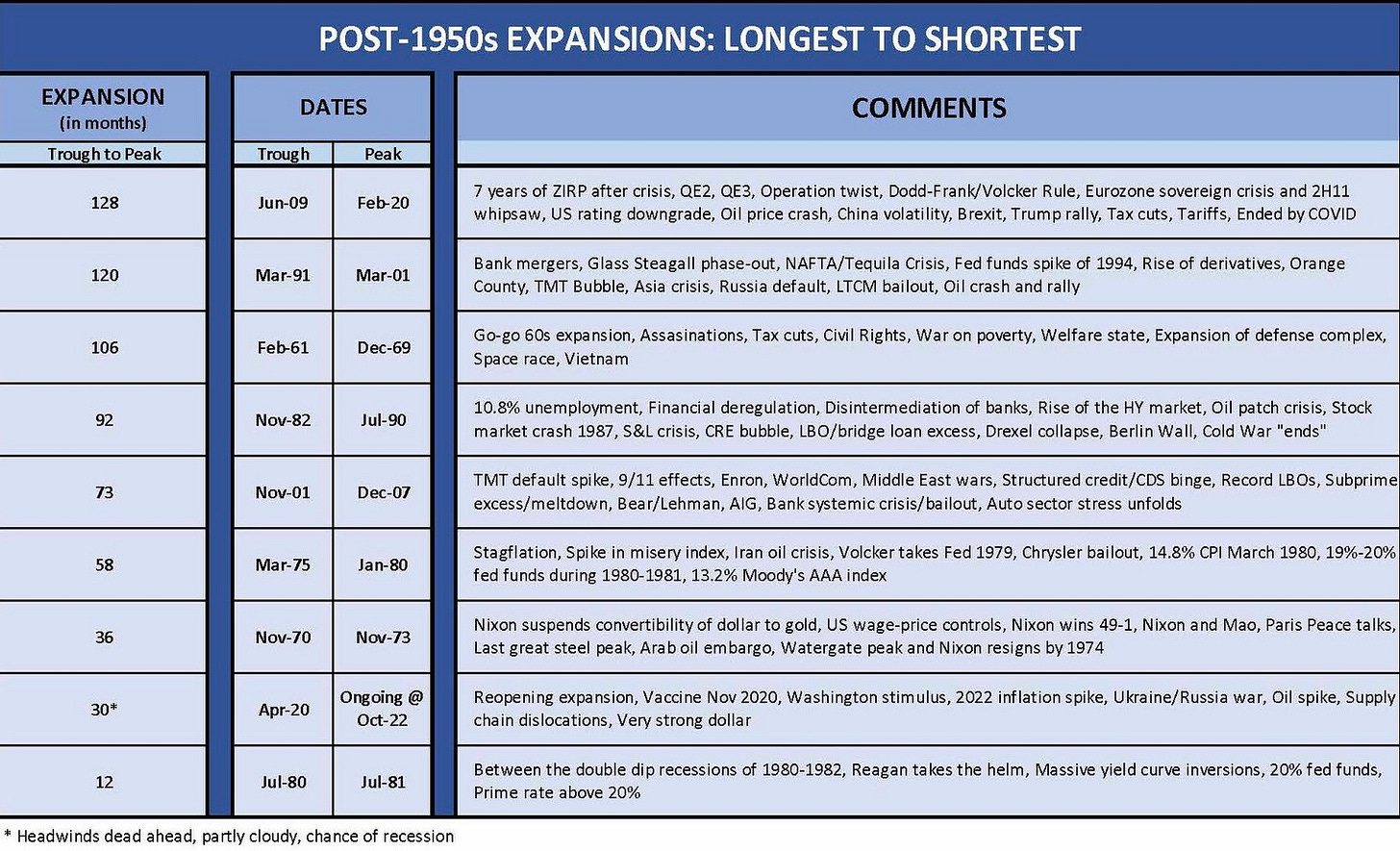

We detail the business cycle expansions from longest to shortest since 1961 and detail key events of the periods.

We look at the economic recoveries of the post-1950s era in descending order of how long they lasted. We detail that in the chart below. The events of those periods as listed in the chart were critical, and I even left a lot out.

The pressing question of late has been whether we are already in a recession. I’ve touched on that subject in a few of the early pieces, including Business Cycles: The Recession Dating Game. We posted that earlier today. There, I looked at NBER’s Business Cycle Dating Committee and how they operate in terms of “timeliness.”

In the end, no one owns the “recession stamp” in a formal regulatory way even if history has treated NBER as the “official” recordkeeper of dates. NBER is a nonpartisan independent entity and not a governmental agency. The full history and list of members of the independent Business Cycle Dating Committee is covered in detail on the NBER.org website.

As we stay on the expansion vs. recession topic in this commentary, another twist on the recession question:

Could we be set up for the shortest economic expansion since the stagflation year of 1980?

Those early 1980s topics keep popping up these days. That’s one of the reasons I’m spending time on multicycle lookbacks as we start up a regular market commentary. So much of what is going on in this market – starting with high inflation – hearkens back to the 1970s and early 1980s with high inflation metrics across a wide range of CPI line items. I’ve been perusing the old BLS reviews of the period—part nostalgia and part “Holy double digits Batman”—and like today, we were seeing major disruptions in global markets, energy sector volatility, currency whipsaws, and domestic political stress. But there are also important differences that must be factored in. As they say, history matters as long as you frame the clear distinctions between past and prologue

Key Takeaways

The current expansion is shaping up as a potential early victim on inflation: As I detail in the chart, the post-COVID expansion of today is at 30 months and counting. Across the list of expansions since the early 1960s, the only shorter one was the brief 1-year expansion wedged between the 6-month early 1980 recession (Jan 80-Jul 80) and the 1981 to 1982 recession (Jul 1981-Nov 1982). The 1980 expansion of 12 months was an interim break in what many typically call the 1980-1982 double dip. A common theme for cycles that came after 1982 was that a victory over inflation was the tailwind that allowed the Fed more room to maneuver. In the market today, the inflation spike leaves less room.

That first big bull market in the 1980s was supported by the public’s belief in the Fed’s unwavering commitment to fight inflation at the first sign of trouble. That helped in the 1990s as well. We have an upcoming UST curve series that will look at the years of UST curve migrations from the 1980s to current times, and that lack of a high inflation stretch made it easier to forget how much trouble inflation can cause. Those of us that came of age (working and voting) in the 1970s simply can’t forget. It was ugly. Vietnam, a President who had to resign, inflation spikes, odd-even license plate days to get gas. Only depression-era parents like mine said “you have it easy” as I was ringside for high inflation and seeing long lines by the unemployment office next to the public library. Those of us who were short of draft age did have it easy in fact. In the aftermath of COVID and now with inflation, these are stranger times than 1975 or 1980.

The comparison of today with 1980 is looming larger now: For this current (potentially abbreviated) expansion, there is no hiding from the stagflation years comparisons. After all, both periods featured high inflation and the aggressive use of monetary tools. The current Fed action is quite mild compared to what Paul Volcker had to wield —the 1980 recession saw a 22% Misery Index, so Volcker had a major battle on his hands. There were industries in transition facing massive challenges (think autos on fuel efficiency and the oil connection), politics were not too friendly domestically (Reagan vs. Carter looks like a love-in compared to today), and the Middle East was not exactly user friendly (Iran crisis of 1979). The oil crunch of 1979 had spilled over into 1980-1981 with some supply hoarding and inventory building by the “major integrateds” who drew on bad memories from 1973-1974. That only inflamed the price action while ironically driving an ensuing supply boom (and eventual oil price crash) on the search for new sources.

Volcker memory lane (nightmare alley) will color the scenario spinning: As Volcker took on the inflation challenge, some at the time felt Volcker showed up with a gun for a knife fight (the former Merrill CEO was in the Reagan cabinet). The scale of the double dip recession was alarming politically as the manufacturing sector was spiraling. In contrast, a slew of the most hawkish critics of the current Fed response will say that the Fed is showing up with 16-ounce gloves where a Stinger is better suited. In my view, there’s a lot to be said for sustained caution in the current market given the much larger, more complex and intertwined global markets. There are many points of potential volatility in 2022-2023 that are unpredictable (currencies, derivatives, and bank system interconnectedness, etc.) and further damage to economic performance (trade flows) is going to be hard to avoid.

Low inflation and a supportive Fed have driven some new expansion records: As the market discovered in recent decades, a supportive Fed does not always run in parallel with vigilant oversight – whether by regulators or by major banks and intermediaries. The post-credit crisis monetary regime and easy money policy especially has had plenty of critics. However, it’s hard to argue with the results of very long periods of economic growth. The favorable outcomes were evident in the post-crisis expansion of 128 months and the same in the prior 120 month period in the boom years of the 1990s.

The TMT boom years in equity and debt saw the US make extraordinary gains as a world tech leader. That came after the 92 months of the 1980s boom that saw a debt-fueled corporate sector drive a doubling of nominal GDP and explosive growth in the services sectors. Disintermediation in financial services powered the credit engine that drives growth. The pension and mutual fund demand for debt was consistent with the maturing of the baby boom years and the rise of retirement savings. The only cycle to break up a Top 3 sweep in the post-1980 era was the GoGo Sixties expansion at 106 months.

The capital markets excesses played an unplanned role in the supportive policies: The pushback to the positive view of the Feds strong performance in protracted expansions has a long list of objections, but we won’t tackle that here. Booms, busts, excess and missteps leading to reforms and enhanced regulatory adjustments are always part of the debate. The “creative destruction” thing (I always hated that term with my declining industrial town heritage) that economic wonks talk about was alive and kicking across these periods. The “creative” part was there, but the destruction might have been mitigated by more prudent industrial policy and the right investment incentives. Worries about creative destruction are often dismissed, but they should with the caveat that “one man’s Schumpeter’s Gale can be another man’s perp walk”. Some of the financial shenanigans (cleverly or not so cleverly disguised as creative destruction) demonstrated in the 1980s brought the perp walks on insider trading, etc. That was before WorldCom and Enron showed up later with a new scale of fraud with Enron but old school fraud in WorldCom’s case. The creative impulses also were evident in the tech bubble IPOs. Unfortunately, some of those exploding IPOs had Shiva as co-manager. So value destruction did follow.

Innovation and credit drives expansions, but too much brings corrections and risk aversion: The rate of change in the elongated cycles brings financial aggression and sometime a bridge too far in financial engineering. Builders build until the market screams stop. Underwriters underwrite until more deals blow up and OTC market-makers fold up their tent. Structurers structure until the derivative counterparty lines hit limits and bids are wanted with too many sellers. The pressure of rising stock prices always brings the challenge of how to keep the party going. Credit brings expansion and too much credit brings bubbles. Tightening brings recessions and too much tightening brings crashes and default cycles. That sounds like elevator music, but it applies to this history of expansion and recession. The structured credit and RMBS excess of 2004-2007 created a crisis that brought the world protracted ZIRP and QE. That level of support in turn brought the longest recovery since the Great Depression. Before the post-crisis, Fed-supported expansion, the waves of new financial product flow brought the biggest global systemic threat in history.

Each cycle came with very distinct structural pros and cons, opportunities/challenges: We tick off the cyclical transition histories in a separate UST curve history collection I am readying, but the histories of these cycles were part of a post-stagflation period of accelerated structural change in the economy from manufacturing to services to banking. When the smoke clears, the US is the #1 producer of oil and hydrocarbon liquids, is by far the global leader in technology, is the largest economy in the world, and has a useful regional free trade deal that offers a lot of room for global competitive advantages (if properly managed). On the side of “brief rebuttal” moments, the US manufacturing sector has been devasted across 40+ years, the US is dependent on global supplier chains, the US has not been this politically dysfunctional since Burr shot Hamilton, and the global markets face an inflationary spike. Inflation in the US has created an overriding priority to address it even if it causes a protracted recession. After all, the recession worked last time (1980-1982). The world is also facing a global geopolitical backdrop where nuclear wannabees and well-established nuclear powers hate our guts with one of them (Russia) seeing its leader get carpal tunnel from nuclear saber-rattling. That qualifies as a “con” even if NATO expansion and Ukraine winning in a “pro.”

Bank system interconnectedness remains Systemic Enemy #1: As headlines around European banks heat up, we are seeing some flashbacks to early 2016 where the Swiss and German banking kings were getting some bad press. The need to manage financial system risk always gets highlighted when there are extreme moves from the macro level (rates, currencies) as directional bets get made and hedging needs grow. The OTC derivative risk exposures are always hard to frame (collateral concentrations, counterparty default risk, etc.) even as the time horizon to stabilization gets extended (how far out do we need to look?). The volatility in the markets also brings back counterparty risk excess. That worry will run hot even if the risk in theory is much better managed now. The Archegos losses of 2021 were a shock since they looked more like a late 1990s problem that would have been cleaned up by procedures put in place after the 2008 crisis. “P&L axes” is a human problem more than a measurement issue. A bad business decision on risk exposure is not fraud. That is usually when some department heads get the trap door.

Beware financial system pressure in 2022-2023: Right now, asset quality is quite sound in the US from major banks to major BDCs, and the banks claim to be ready and the regulators sanguine on the ability to navigate regional recessions (Europe) or global downturns (the US+ Europe+ China combo as the linchpins). Europe will be looking shaky ahead on asset quality while EM dollar debt borrowers will face significant questions about how asset-liability management will hold up in the face of a very strong dollar. Hedging or failure to hedge for borrowers brings markets risks, credit risk and counterparty domino risk. That was a big factor in the 1995 to 1998 time frame when EM getting roiled. Bank counterparty risk exposure went systemic when counterparty risks tied the banks together in the RMBS boom.

The end of the 1980s boom was less threatening in the age before derivatives. The regulatory seizure process would unfold, and branches would be sold off. The same with the S&L crisis. The market was heavily exposed to asset quality pressures in the late 1980s/early 1990s (Texas banks, S&L crisis, bridge loans with brokers, commercial real estate loans, leveraged finance, etc.), but those did not derail the expansion earlier. In contrast, the 1990s saw an Asia and EM bank system crisis ahead of LTCM and Lehman headlines of that same period. Those events brought Fed easing in the fall of 1998, a year when systemic risk was giving the world some things to think about. The market quickly forgot, however, after LTCM became a more distant memory. The 1% fed funds rate to start 2004 (more than 2 years into the expansion) made “every day a new day” on leveraging and growing counterparty exposure. The pre-crisis years of mortgage and structured credit excess leading up to the 2007 credit cycle peak is a well-traveled history. We will look at that more in the UST series.

The supply-demand imbalances of lenders vs. borrowers will be back: I was just binging a DVD collection of Winds of War (Herman Wouk’s novel collection) with War and Remembrance teed up next. The subplots of the UK desperately needing money, Germany needing oil, the Soviets needing supplies, and FDR trying to find budget room in a deeply divided country (at that time, on foreign involvement) are not too far from todays risks. To add to the parallels, Mussolini was trying to navigate some challenging global relationships before he had the prevailing winds sized up.

It is a reminder that in the end it all gets back to money—who has it and who gets it. As we ponder the potential for economic and political stress across Europe this winter, we also face the fact that two of the largest holders of UST securities (China, Japan) are in a geopolitically fraught Asia-Pacific region. That reality comes as the Fed’s QT process is underway and the Fed balance sheet has a lot of weight to lose. The Fed was a big source of UST and mortgage demand. The deficit spending makes the 2022 backdrop much different than the balanced budget period of 2000 as the economy was heading into recession soon.

Those Econ 101 supply and demand lines apply to sovereign debt: The current trend lines in figuring out who the net lending countries will be point at higher cost to borrow for sovereign debt on both tightening by central banks, on inflation, and in terms of spiraling needs for more money in the period ahead, i.e., the UST. That is especially the case if more major owners seek to sell or slow/stop buying. If everyone is borrowing and fewer are net lenders, that obviously creates some issues when the lender pool shrinks. The ability to line up sellers and buyers of sovereign debt has the added challenge of currency pyrotechnics and strained relationships across sovereigns as money is being poured into war and energy subsidy costs.

The macro-to-micro moving parts are daunting, and it is not great for cyclical longevity, raises costs in the private sector, and has the effect of shortening real estate cycles also. The elevating front end could pressure leveraged borrowers in a way not seen in decades. The rise of private debt and direct lending have also been a major factor in more leveraging in the small and midcap sectors of the US. Offshore, we could see a lot more noise ahead as we did in the 1990s. Sovereign credits and currencies will see mixed demand.

Policy challenge can influence cycles: The 1980s and 1990s boom cycles were built on split party control. Split authority used to be preferred by investors and markets. That will get tested in the current Congressional nuthouse. The best of the 1980s and 1990s came with checks and balances and striking deals in Washington. Reagan and Tip O’Neill knew the job had to get done. Today the challenge of basic functionality gets bigger and harder to get around and over. The only thing the right and left agree on is shooting the centrists. For now, “shoot” is a metaphor.

The economic challenges are our main concern as investors and analysts, but the political challenges could worsen that effect in constraining policy flexibility (and utility) as each side digs in. I grew up in a house where Thanksgiving dialogue in 1968 featured voters for Nixon, Wallace, and some disgruntled Clean Gene McCarthy supporters who held their nose and voted for Humphrey in the election. At least people moved on each time. The current backdrop in the US has finally eclipsed 1968. In domestic politics, Sinclair Lewis’ It Can’t Happen Here is making a comeback. That can’t be good when someday a fiscal cliff decision becomes a High Noon rerun.