Credit Performance: Excess Return Differentials in 2023

We review running excess return differentials for some key metrics to frame relative compensation for credit risks.

We look at relative excess return differentials across some credit tiers for a measure of compensation received for credit risk incurred and offer some historical context.

We look at the running excess return differentials for IG vs. HY, along the speculative grade divide (BB vs. BBB), and for the Hi-Lo intra-HY comparison (CCC vs. BB).

Excess return differentials overall in HY vs. IG saw a strong move early in the year before a regional bank whipsaw upset the rally, then the second disruption came in the fall on the UST steepening rattling risky assets from equity to HY before a very strong finish.

2023 wrapped with HY OAS just below the 2014 lows and close to the 2018 lows, but a tailwind still can be found in the fact that the all-in yields of 2023 are materially higher than those seen in 2018 and 2014.

An important X-factor in 2024 for demand will be whether the refi cycle in HY kicks into gear and bolsters demand with higher cash coupons.

In this commentary, we dig more into the running excess return differentials across 2023 and how well the credit investor did in getting paid for taking more risk (or got paid less for less risk). The year end lookbacks are always a good exercise even if just to take inventory of how the backward-looking facts played out vs. the early year forecasts. That always helps in the next round of forward-looking handicapping. What worked? What didn’t? What was in line? What surprised?

Investment time horizons and reinvestment (i.e., compounding vs. income drawdowns) vary by investor, but the narrow annual drill helps in taking stock of risk-return strategies. The power of the all-in yield certainly trumped the concerns around the relative tightness of the risk premiums. The yield-starved demand profile seen in the market rewarded the risk maximization strategy in IG and in HY with its wild, bullish finish.

In a market like the current one with so many major risks lurking on the perimeter (e.g., geopolitics), some that seemed to take a back seat since they lacked easy quantification. On the other hand, UST deficits with soaring interest bill will only get worse in 2024. The market seemed to set aside how that could influence the UST curve in 2024-25.

For 2023, the day-in, day-out exercise of inflation watching, Fed handicapping, industry analysis, and issuer monitoring played to the optimists. The expectation to get paid for taking credit risk is important for the high probability risks, and the probabilities favored soft landing or no landing as the year proceeded.

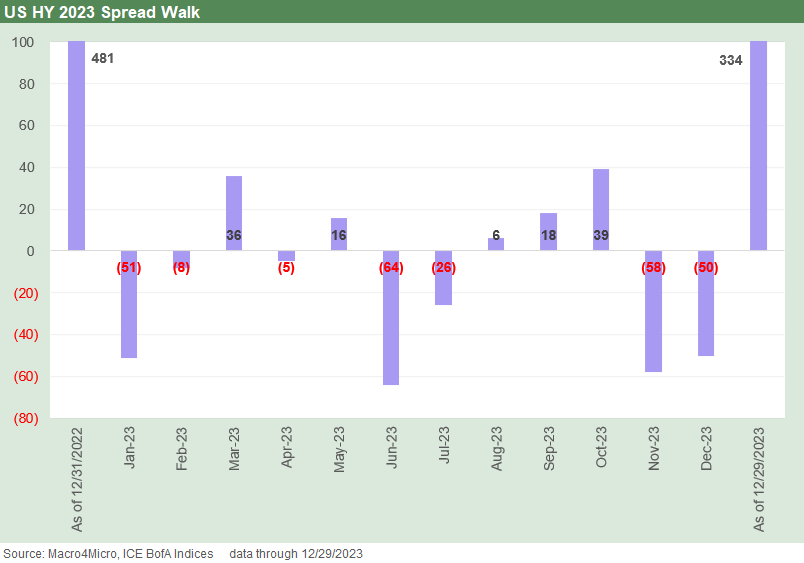

The chart below breaks out the ride in spreads across HY during 2023. There have definitely been more volatile years (much more), but this one is perhaps one of the more surprising given that it was the first major inflation and tightening cycle since the early Volcker years.

Gauging the Fed response in terms of the real fed funds rate has been a rough call. The two historical data points for the inflation responses are comprised of the success of Volcker in the early 1980s and the failures of Burns/Miller in the stagflationary 1970s.

As we look back across time for calendar comps since the 1990s, that inflation and tightening backdrop will lurk as one set of factors that will make this cycle (and 2023) somewhat of an outlier in the overall backdrop.

In framing the minimum expected credit risk compensation, one challenge is framing how the portfolio mix will transition from a period of protracted low rates to one with materially higher rates. After such a protracted period of ZIRP and QE mixed in since late 2008 and during COVID, the UST curve will tend to drive yield to the top of the list as the asset allocation reviews get phased in over the coming years.

In an OTC market like HY and IG, demand can trump relative value in historical context. Review of excess returns helps in that process, but total return tends to rule the decisions and ranking. HY is obviously the more volatile in credit spreads as underscored by the chart below, and IG total returns still offer a very sound way to even out the cyclical factors driving fundamentals and the UST curve risks that are by no means an easy call even with all the bullishness to close out the year.

A look at excess returns…

In our first piece reflecting Friday’s closing data, we looked at monthly total return and excess return quilts (see Return Quilts: Resilience from the Bottom Up 12-30-23). The results showed a very mixed year with major events unfolding in geopolitics (Ukraine-Russia hangover in energy and European economies, Israel-Hamas War, Taiwan-China risks dead ahead). The sea level realities closer to home included a brief but shocking regional bank upheaval and bouts of UST volatility that went very negative and then went very positive.

That UST swing drove all major asset classes and basically all risks were rewarded, with 2023 returns finishing in impressively positive fashion. The old adage of “Don’t fight the Fed” was in play for most of the year with the overriding question of when the Fed’s “fight” against inflation would take a step back. It is still not 100% clear given the ability of the Fed to still run a protracted pause (rather than ease) subject to the data. The other less-established adage is “Don’t bet against the American consumer.” That was supported again in 2023.

For this part of the continuing year end review exercise, we look at excess return differentials from three different angles:

· HY vs. IG excess return differential: The excess return for the IG basket vs. HY basket tells a story in historical context. In a good year for credit assets, it is also important to keep in mind that 2023 was only a “modestly above median” year for incremental excess returns for dipping down from IG into HY.

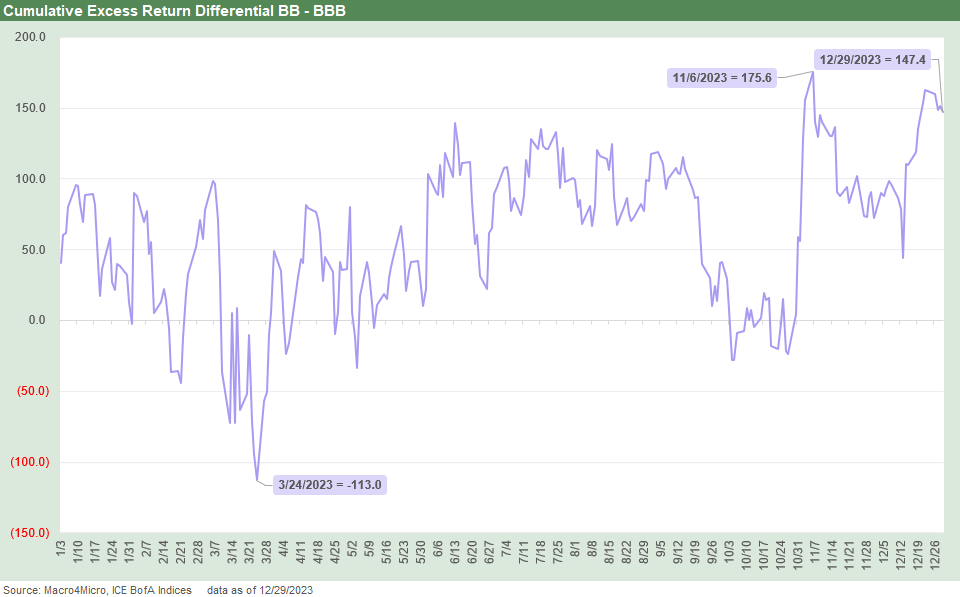

· BB vs. BBB excess return differential: The speculative grade divide has long dominated the thought process for IG heavy and BBB heavy portfolios. The BB-BBB differential measures the credit compensation for stepping across the divide. From a half empty perspective, it can also measure the “cost of being wrong” on how the rating agencies might move on a downgrade or upgrade.

· The CCC vs. BB differential: We look at this metric as a Hi-Lo risk comparison within the broader class of HY. In the financial media and even equity markets, many more still say “junk” than “speculative grade” when the HY mix presents an extremely wide range of risks. The reality is the long-term default risk in the B tier is exponentially higher (literally) than the BB tier, and the same for the CCC tier vs. the B tier. These differentials can really swing around across the cycles and notably in the CCC tier as “credit risk” pricing turns into “high risk equity price volatility.”

Asset allocation in credit often comes down to this simple (and in many ways arbitrary) breakdown between investment grade and speculative grade. The HY-IG excess return number is thus an important one. Historically, the middle tiers of BBB and BB produced the best risk-adjusted returns across longer time horizons. As a result, the “HY Lite” strategy has taken on great appeal. In past years the “credit barbell” was another favorite that turned on the ability of the manager to sort out the CCC tier values.

The vast majority of CCCs do not default even in a bad year, and those who have the expertise to handicap risks at the issuer level or within and across the capital structure are the types that will be in the vanguard of private credit and direct lending as well as making markets or providing liquidity to the CCC HY bond issuers. The development of those trends will be interesting to watch in 2024.

HY vs. IG in excess returns in historical context…

Refer to the chart at the top of the page for HY vs. IG cumulative excess returns across 2023. The chart above shows incremental excess return compensation for the HY basket vs. IG came in at almost 4.5 points higher in excess returns for HY than IG. If we look back across the pre-COVID period back from 1997, we see 10 years higher and 14 years worse than 2023. Another interesting number is that the differential was negative in 10 years for a broad range of reasons. An above-median incremental compensation pickup beats the alternative, but that was not a banner year. It was a good year in multicycle context.

If we look at some past years for excess return differentials in the vicinity of the 4.45% 2023 number, we see 2019 at +2.7% excess return differential. That is a useful one to consider since 2018 was an ugly lead-in for HY and IG both despite being a cyclical expansion year. Abysmal asset performance often sets the stage for a good rebound year unless the credit cycle is cracking and core fundamentals are weak (think 2000-2002 stretch). The year 2018 saw both HY and IG generating negative excess return as well as being ugly for equities.

The 2018 to 2019 transition offers a reminder of the ugly 2022 for risky assets. The “bad year bounce” often benefits the following year unless the cycle has turned down. That cycle held in 2023 and even saw a 3Q23 GDP close to 5% with record high payroll as of Nov 2023 numbers. Back in 2019, the cycle was weaker (just check out the FOMC statements and not the political speeches), and the Fed eased three times. That also offers some food for thought on the way into 2024.

We also saw +4.7% running excess return differentials for HY vs. IG way back in 1999 with US HY putting up +6.1% excess returns and IG at +1.4%. That was a year when the default cycle was already underway by year end even as tech-centric equities saw a +86% return on the NASDAQ. TMT would soon implode along with the equity market, and the CCC tier would plunge to last place in excess returns over three consecutive years (2000, 2001, 2002).

The post-1999 period saw waves of major falling angels (Enron, Tyco, WorldCom, etc.) from BBB into HY that in turn brought considerable market upheaval in credit tier performance relationships. The year 2000 would see negative excess return differentials for HY vs. IG of over -10% in 2000 and 2002. The TMT credit cycle saw the second and third worst differentials since excess return data is available, with 2008 the worst at almost -17%.

Another year that is not too far away from 2023 was 2012, which saw a HY-IG differential of 5.7%. That year is interesting since it was a banner year for credit risk not long after a crisis. The economy was getting its legs back on ZIRP and QE and a slow rebuild of payrolls. Europe had semi-resolved some of the more dire scenarios on the bank and sovereign systemic support (“Whatever it takes” by Draghi in July 2012). Systemic risk easing reduced fears of credit contraction and more bank paper volatility in the BBB and BB tier. Financials dramatically outperformed in 2012.

During 2012, CCC and weaker B tier names in the US soared and a refinancing-and-extension wave of new issue volume supported the HY market with +13.6% excess return for HY and 7.9% for IG. 2012 posted great numbers in both IG and HY.

That higher risk appetite extended into 2013 with strong equity performance and a HY rally despite the taper tantrum and bear steepening that hammered duration in total return metrics. The year 2013 sent HY to a HY-IG excess return differential of +6.7%. HY posted +9.5% excess returns and IG +2.8% in the taper tantrum year. The year 2013 was also the best year for the S&P 500 in the decade after the credit crisis. Those profiles give some context to the 4.5% in 2023.

In the context of the 2012 and 2013 comparison, it would be easy enough to say not much has been resolved in 2023, but we would argue much lower inflation and some born-again doves on the FOMC have been a major source of sentiment support into 2024 (UST funding needs be damned apparently). The Fed still has not eased – yet – and UST inversions are still the order of the day. There is still plenty to debate in a world where a perception of high certainty has not always been rewarded.

The chart frames a running BB vs. BBB differential for 2023 of just under 150 bps, so investors at least got paid for the risks.

If we do the same exercise as in the prior chart and look back across the pre-COVID cycles to 1997, we see only 6 years negative vs. 10 years negative for the HY-IG comparison. The 2023 return differential is around a median area performance for the 24 years before the COVID cycle.

The excess return differential of BB vs. BBB in 2023 was just below the median. Positive beats negative, but there are plenty higher than 2023. A good comp is 2019 at +2.1% when the BB tier came in at +10.2% and BBB at +8.1%. That credit pricing bounce came after a very ugly 4Q18 that unfolded shortly after the 10-3-18 HY OAS low (note: these are ICE benchmarks). For 2023, BBs weighed in at +7.1% and BBBs at +5.7%.

As mentioned above, the speculative grade divide is always a focal point given its significance in defined portfolio credit parameters in mutual funds and pensions. There is also the regulatory requirement factor depending on the industry. The IG vs. HY distinction was great for a demonstrated exercise of market power by the major NSROs under the old regulatory framework (and did not hurt pricing power either).

The market got a fresh taste of BB vs. BBB regulatory arbitrage during the COVID Fed relief process. The Fed was spilling QE over into corporates. The program was initially designed with the IG designation looming large. At least as it was being set up, the Fed was relying on the rating agencies after all the reform years noise when the Fed and Washington were chanting “don’t rely.” The confidence boost from the Fed worked like a charm regardless of such issues since it was part of setting off a refi and financing boom. That boom of 2020-2021 will be a big part of the HY story in 2024-2025 as those bonds see refi needs and coupons get reset.

These days, IG vs. HY is less about “regulatory arbitrage” and more about framing cost effective access to markets and gauging demand along the yield curve (e.g., the relative weakness in HY demand for the long end of the UST curve). There is also the question of framing what “IG covenant” variations are required just below the divide in BB tier. Some additional structural requirements might be needed in the BB tier (e.g. subsidiary guarantees).

We have looked at some names where the high BB issuer has better protection than the low BBB comps and notably with Holdco structures. Whether banks demand some structural edge is another question for the “cuspy” names. The banks can easily adjust structures on event-driven downgrades while bondholders along the speculative divide tend to be stuck.

The CCC vs. BB tier excess return differential is the more volatile metric across a cycle given the dramatic swings that can unfold at the bottom of the credit tiers. We see two big swings in the chart above before the wild and positive finish in Nov-Dec.

For CCC vs. BB excess return differentials, the 8.9 points is a big number given where the year started coming out of the tightening cycles and myriad uncertainties around the cycle and what the inversion and upward move in the curve would mean for the most leveraged borrowers with the most layers. The low end was not helped by the regional bank turmoil and questions around credit contraction.

As we look back across the 24 years ahead of the COVID crisis, we see more than half the years negative for CCC vs. BB tier differentials. That is a sign of how challenging the CCC tier strategy is for many funds. Another one of the “oldie but goodie” sayings is “everything is AAA at a price” that works well in tandem with “Buy the CCC that is a CCC on layers and leverage and not on bad fundamentals.”

The 8.9 point differential performance of 2023 is in the top quartile across the years from the late 1990s. We see four years with double-digit negative differentials (2000, 2001, 2008, 2015). The year of COVID (2020) was running deeply negative early in the year but rallied back to “only” a -4.8 point shortfall.

For other historical comps and food for thought, we see +8.7 points in 2006 after a +7.1 point differential performance in 2004. Those were during the years of raging bull risk appetites (as we now know, that all ended badly with a housing sector, structured credit, and bank system meltdown).

We see a +9.7 point differential for CCC vs. BB way back in the credit cycle peak of 1997. That was just before the TMT credit cycle sent the BB tier to its leadership role in the HY basket mix. The credit cycle crash in 2000 to 2002 grew the CCC tier as well as setting records for the longest (not the highest) default cycle.

Another interesting comp year was 2012, when both CCCs and BBs posted an impressive rally that ran alongside a new issue refi boom with Fed support. During 2012, the CCC tier posted +18.7% in excess returns vs. the 12.2% posted in 2023.

2023 was one of those years where the CCC rally surprised many (including us) in how it was able to tighten so dramatically in only two months as CCCs compressed by -144 bps vs. -120 bps by BBs across Nov-Dec. For the full year, CCCs rallied -319 bps and BBs -104 bps.

The CCC tier comes with the asterisk that spreads can sometimes rally on index dropouts on default when the favorable mix shift can impact OAS when a high-spread issuer drops out of the mix.

As one might expect, the big swings in CCC vs. BB excess returns across cycles or within a year are set by the behavior of the CCC tier. It is not as if a portfolio manager sets his sundial on CCC exposure by its relationship with the BB tier. That manager presumably looks at the pricing and return potential over a defined time horizon or in the context of theoretical recovery value for any given CCC name.

CCCs are truly a name-by-name exercise in a credit tier with an extremely wide range of prices within the tier. (In reality, many CCCs were purchased as Bs and BBs.) The toolbox for cash bonds and loans vs. CDS can be very different as Hertz dramatically demonstrated with its 26-point handle auction price vs. par plus on exit. That was one for the ages.

Summary

The net takeaway from running excess returns for HY vs. overall was that investors got paid for taking credit risk in 2023 as spreads narrowed in a HY index mix with low weighted average coupons. The overall performance of 2023, in the context of the cycles since 1997, can be rounded to a median level of compensation for their risks. That said, the year saw an outperformance in risk compensation for CCC risk vs. BB in longer timeline context.

That type of performance in 2023 took much to go right and for many of the risks lurking (some potentially systemic in profile) to head back into the cave. That is what happened. Now, the market moves on to 2024 where we might not be so lucky with the outliers. The UST rate risk factor for duration vs. credit risk pricing remains the overriding variable.

We will stick with IG as the safer route in 2023 with higher quality HY. We will watch for the potential for a refi wave in HY that brings higher coupons and higher cash flow generating assets in the new age of post-COVID coupons. At some point, prudent liability management demands extension, and rates and risk appetites are friendly now.

A pickup in refi action would imply strong credit demand is alive and well and refinancing would be net neutral on supply. Gauging the scale of leveraged M&A could move the needle but also could be redirected towards more private credit rather than HY bonds. The Fed, UST rally, and favorable inflation tailwinds are making those refi decisions easier for corporate managers. The corporate borrower might not be as optimistic as the credit, equities, and UST markets.

See also:

Coupon Climb: Phasing into Reality 12-12-23

HY vs. IG Excess and Total Returns Across Cycles: The UST Kicker 12-11-23

HY Multicycle Spreads, Excess Returns, Total Returns 12-5-23

HY Credit Spreads, Migration, Medians, and Misdirection 11-6-23

Quality Spread Trends: Treacherous Path, Watch Your Footing 10-25-23

Contributors:

Glenn Reynolds, CFA glenn@macro4micro.com

Kevin Chun, CFA kevin@macro4micro.com