PCE April 2025: Personal Income and Outlays

The price creep remains light until the full tariff impact plays out, but the “Newtonian Law” of accounting still applies.

I don’t see the words “no reaction.”

The tariff facts of life include the fact that the buyer/importer pays the tariff (even Trump indirectly admits that now from time to time by threatening Walmart, Mattel, etc.). The cause-and-effect is that there is always a reverberation somewhere along the transaction chain from the US buyer/importer (e.g. manufacturer, retailer) to the end of the customer chain for goods (e.g. the household). Framing that “reverberation” is the trick.

The reaction can be price cuts from the seller (e.g. China price cuts) to the buyer (lower margins/earnings) to offsets executed by the buyer to mitigate the tariff cost damage (cost cutting, productivity countermeasures) to the biggest fear of price increases and inflation. No one can hide from the earnings or price risk. If “offsets” come in the form of price cutting, that has a darker set of multiplier effects including payrolls. It all takes time. The higher the tariff and the broader the targets, the bigger the challenge domestically.

The PCE price metrics this month (+2.1% headline PCE inflation, +2.5% Core PCE) are good news, but the challenges are just beginning with Section 232 flow-through impacts on price and volume. The tariff pauses and legal actions keep drama high, and politics will be played by all. The rule of “politics=policy=economics” still applies. The game theory could shift for the major trade partners subject to a SCOTUS timeline and decisions or any new decision on the “reciprocal” motions from this week.

The retrenchment in outlays (Personal Consumption Expenditures) is consistent with the revision we just saw in the 2nd estimate of 1Q25 GDP, but the personal income trends in today’s PCE release tell a favorable story while also signaling a worried consumer on the PCE line and savings rates (see 1Q25 GDP 2nd Estimate: Tariff and Courthouse Waiting Game 5-29-25).

Below we update our rolling monthly report on Personal Income and Outlays that includes PCE Inflation histories. We update recent data and make edits in the histories where appropriate. We retain some of the history text in part for new readers and especially for our student readers who might be new in this discipline.

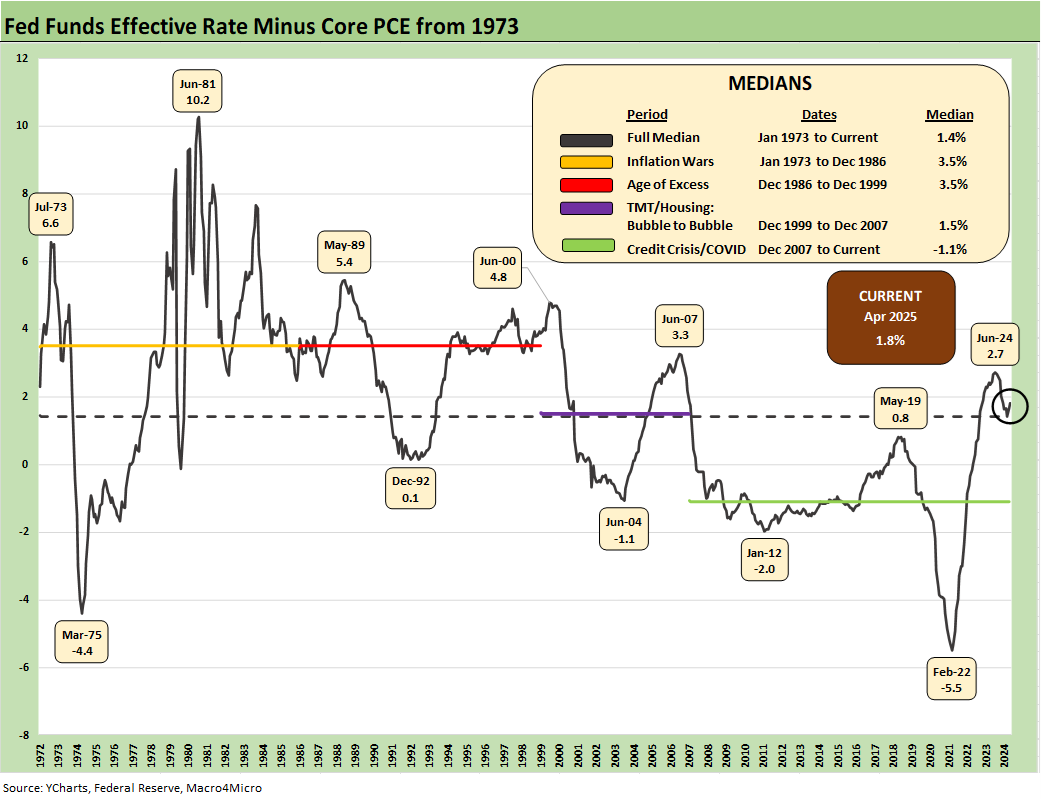

The above time series updates “fed funds minus Core PCE” since 1973 for a read on “real fed funds” and to what extent the Fed is engaged in “real” tightening as opposed to the “closet accommodation” that we saw in much of 2H22 when tightening was moving into higher gear but badly lagging inflation.

The long-term differential median is +1.4%, and the differential now is +1.8% in a small sequential uptick from March. That leaves room for easing, but the final judgement on actions comes down to how you see the tariff threat and what that might mean for forward inflation. There is not much room in that differential for an adverse move in Core PCE at current fed funds rates. A move higher for tariffs could push that number well inside the median and even send the metric into negative range. Anyone who experienced 2022 (let alone those of us ringside for 1974-1975 and 1979-1982) knows the inflation numbers can move quickly.

The “will they or won’t they” debate on whether tariffs cause inflation continues. If you need to play semantics with the “one-time-event, not a monetary thing” crowd just substitute the term “purchasing power” and use long division and elementary school math to ward off PhDs in economics. Consumers see inflation rising as detailed again this morning in the April U Michigan survey. The survey was largely unchanged from March, but UMich indicated internal data that showed relief as the China truce and pause continues.

The survey showed inflation expectations for the next year at the fairly irrational level of 6.6% (up from 6.5%) with long term expectations declining to +4.2% in April from 4.4% in March. A 6% handle on inflation expectations for the year ahead ties into the psychology of the consumer, so that can flow into transaction and economic behavior. That makes it an economic event, and the consumption lines have been fading in macro releases and are evident in sea level results and guidance in earnings season.

The above chart updates the long-term time series for PCE vs. Core PCE across the decades and cycles. We see the 2.6% headline PCE long-term median in the lower left (vs. the current 2.1%) and the 2.4% Core PCE median (vs. current 2.5%). That is dramatically better than where we came from in 2022 but still short of the 2.0% target. Those are good numbers for April, and in the absence of the tariff uncertainty the Fed might have room to cut sooner (in theory).

As the medians highlight and the following charts show, it takes a lot to go wrong to get sustained 2.0% PCE inflation. What no one in the White House seems inclined to point out in the FOMC bashing is that multiple trade wars could cause more than a few economic calamities including stagflation. We are still not getting a full-throated admission from Trump that the buyer pays the tariff although his threats against retailers imply as much. In recent days he even reiterated that he collected $600 billion from selling countries in Trump 1.0. That does not build consumer confidence.

History tells a wild story…

We include a box of “critical events” in the above chart to jog memories for the older crowd and a historical checklist for the new folks on the block. The 1973 to 1975 period was a turbulent one for domestic politics and geopolitics (Israeli war, Arab Oil embargo, the fall of Saigon, etc.) while 1979 offers some intense history in the Middle East also (Iran, fall of Shah).

The1980 to 1982 double dip recession saw the peak inflation fighting of the Volcker years with a few 20% fed funds moments in the mix. The inflation fighting by Volcker was helped by rising oil production from non-OPEC sources (North Sea, Mexico, Alaska, the Lower 48, etc.) and a breakdown in OPEC discipline. Oil crashed in 1986.

The latest round of volatility will keep markets on edge for any more signs of stagflation, which was on the curse list for Nixon/Ford and later Jimmy Carter. The current market is the closest we have come to a legitimate stagflation threat since the Carter years. That weighs heavily on the Fed and FOMC. Nobody wants to end up on the “Burns/Miller list” by caving to political pressure on rates ahead of stagflation risks.

The above chart frames the long-term differential history between PCE and Core PCE since 1972. The long-term differential is zero and we currently stand at -0.4%. The volatility around that compressed long-term median flows into the energy wildcard with some food distortions also back in the 1970s. We look at some of the CPI energy and food inflation moves in separate commentaries (see Inflation: The Grocery Price Thing vs. Energy 12-16-24, Inflation Timelines: Cyclical Histories, Key CPI Buckets11-20-23).

The oil wildcard will remain one that Trump and team want to work in their favor. Russian oil supply back on the market would satisfy that oil price plunge ambition even for Core PCE since the energy bill flows into goods and services costs and can impact PCE ex-Food and Energy. Lower energy costs also bolster consumer confidence in the peak driving season and are supportive of the ag sector and in easing freight and logistics costs.

Rooting for Russian supply for the wrong reason clearly has its limitations with the fate of Ukraine a sticking point. A more material trade clash with Canada and the overt hostility shown that country by Trump would be bad for the US and Canada and bad for oil prices as the largest importer of crude with very attractive economics for US refiners.

The above chart looks at a shorter timeline from 1997 to offer a better visual scale separate from the wild 1970s and 1980s. We see deflation in the post-crisis recession trough in mid-2009. We see the collapse in oil prices in late 2015 and then the COVID impact in 2020. Oil is a big headline mover whenever there is a sharp decline or spike, and we have had plenty of both.

The 1997 to current period also shows a rare stretch below the 2.0% PCE line and Core PCE median timeline. It took a lot to go haywire in that time horizon to cross that 2.0% threshold. The events along the way including oil crashes in late 2014 to early 2016 and a financial systemic crisis from 2008 to 2011 (including sovereign stress) to get us there. COVID was a new one for the modern capital markets.

Trump’s focus on increased demand for oil and increased supply by the US (it was already at record highs) was his Trump 2.0 election campaign pitch. His version of low oil was not tied to weaker demand and cyclical weakness from tariff damage. That weaker demand fear on global and regional cycles has hurt oil in 2025. We are down around $60 WTI and such levels call into question domestic drilling economics. Low oil does help the inflation story and is especially helpful as peak driving season has arrived.

The above chart covers the time horizon for DPI vs. PCE from early 2022 as the tightening cycle kicked into gear after March 2022. Life in Jan 2022 was still quiet for Disposable Personal Income, and we see Consumption still running ahead of DPI coming off bullish macro headlines in 2021. The 2021 period was a big macro rebound in GDP off the COVID peak period. The strong macro backdrop in 2021 and heavy dose of fiscal accommodation did not mesh well with residual supply side shortages in goods broadly as 2022 saw the end of ZIRP and a material inflation spike.

Oil was a problem after the Putin invasion of Ukraine in late Feb 2022, and inflation hit a high in June 2022 at +9.1% for CPI as a headline grabber (headline PCE at +7.1% in June 2022) before the steady inflation slide to current rates. Core PCE had dueling peaks at +5.6% for Feb and Sept 2022.

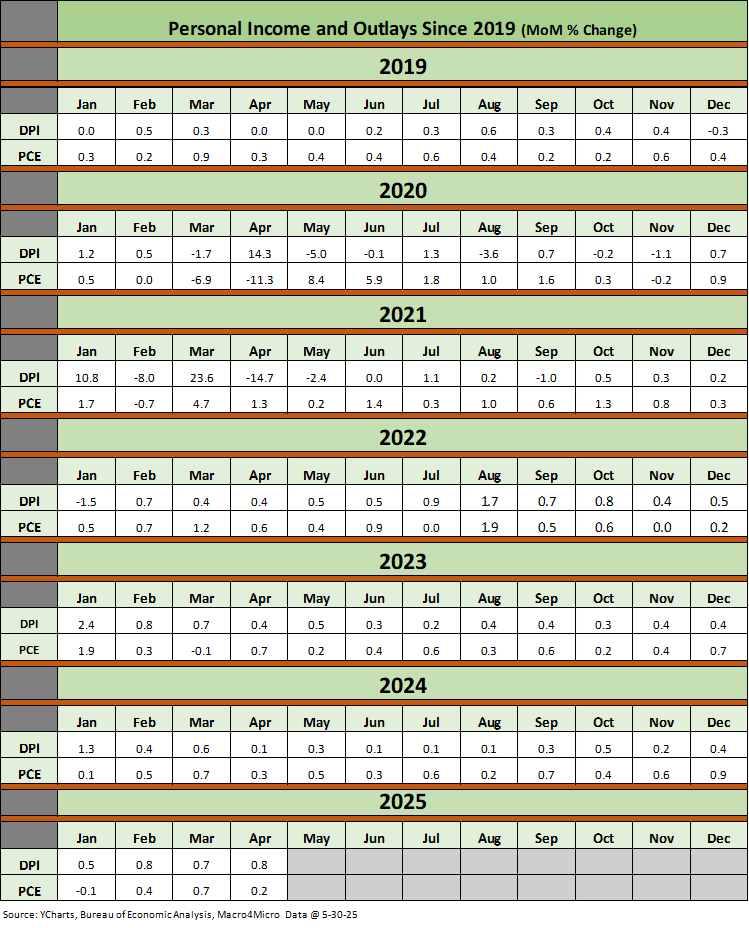

For April 2025, DPI is above the median at +0.8% and PCE is lower than the median at +0.2%. Those consumer income levels can be read as reassuring on the current economic resilience while PCE also tells a story of a nervous consumer. That will especially be the case if we see more disarray in the markets tied to tariffs. Employers and consumers will have decisions to make as the side effects of tariffs unfold. Policymakers and GOP legislators defer to Trump while consumer and corporate investors get to make up their own minds.

The above chart plots MoM Disposable Personal Income vs. PCE as a read on how wild things got during and right after the pandemic peak. These comments are somewhat of a replay each month with some edits and updates. This is a chart we use each month to revisit the DPI swings that came with the three COVID relief/stimulus packages. That included two under Trump and one under Biden. The most recent month (April 2025) shows DPI well ahead of PCE.

As a reminder, Trump signed the CARES Act in March 2020 (shows up in the DPI in April 2020) and Trump also signed the Dec 2020 legislation disbursed in Jan 2021 (Trump seldom mentioned that Dec 2020 one since it was easier to blame Biden and Powell). Biden signed the America Rescue Plan (disbursed in March 2021) that was a demand pile-on (we would argue over the top) in a supply constrained environment (thus inflation). The DPI and PCE wave tied to each of those shows up in the chart above.

The vaccine was announced in early Nov 2020 just ahead of two stimulus actions. That was soon to be a factor in PCE patterns and lag effects. The quarterly GDP numbers in 2021 on the post-COVID bounce were numbers generally not seen since the Reagan and Clinton years (see Presidential GDP Dance Off: Clinton vs. Trump 7-27-24, Presidential GDP Dance Off: Reagan vs. Trump 7-27-24).

COVID was a distinct period for supply chains and supply-demand imbalances. With tariffs and potential trade wars, it will be important to look for similar imbalances whether in narrow product categories or in broad commodities and materials areas. Jacking up aluminum, steel, and seeking even more tariffs on lumber and new tariffs on copper is not a great idea for keeping prices and costs contained. Autos in Section 232 was very extreme. We saw semis, pharma, and aircraft/engines/parts added to the Section 232 pipeline. We have the reciprocal tariffs in a court battle the past week and SCOTUS will be the one who will settle the “emergency tariff” rights of the executive. Trump will start with two SCOTUS votes in his pocket and work from there.

Supply-demand factors are timeless in significance. Washington spends too little time discussing how it fits into their plans. Dislocations that were underway in shipping and freight can still cause many unintended consequences (all bad for consumers).

The typical political game in the 2024 election was to concentrate inflation cause-and-effect on the March 2021 disbursement highlighted in the chart above. The idea is that a single stimulus plan signed by Biden in early 2021 was the cause of all inflation. That is another case of “dumbassery” in Washington tradition. We see it on both sides of the aisle across the decades, but that was an especially dumb sales pitch from the “politically axed.” That Biden plan certainly made things worse from the demand side. The invasion of Ukraine by Russia in Feb 2022 also drove the ensuing spike in inflation to a June 2022 CPI high of 9.1%. That invasion was caused by Putin, who seldom gets mentioned by policy architects as they consider what went wrong in 2022.

The above table plots the monthly Disposable Personal Income MoM change numbers vs. the Personal Consumptions Expenditures numbers across the years from 2019 through Jan 2025. It is an easy scan across key time periods for a look at turning points in DPI (e.g. stimulus payments) or PCE.

One exercise to do from time to time is to look at Table 1 in the monthly “PCE release” for the granular dollar amount on each line. While this month’s personal income pop of +0.8% is good news (see line 32 for the DPI total), the line items can show some volatility. We like to look for gaps between DPI and PCE.

Any reader of Table 1 can simply tick off which lines might come under pressure in the coming months with tariffs including expense lines such as Medicaid or durable goods that face tariffs. The budget bill with the tax cuts and offsets are all over the screen every day, but it is always worth remembering that a tariff is a regressive tax that hits lower income consumers harder. The same is true in Medicaid. Legislators can vote with their party, but the fact is the “buyer pays.”

The basic math is the proportionate impact of tariffs and many basic service costs fall harder on lower income households. The “buyer pays” reality is a legislated fact and the “regressive tax” label is elementary school long division. The response from many to these facts tends to be “don’t get rational or factual, get angry and deny facts.”

This month had a range of revisions from the BEA from the fall through the current release, and we see a fresh set of savings rate numbers. The new saving rate numbers show April at a high of +4.9%, up from the Dec 2024 lows of +3.5% before moving up into the 4% handle range for each month to date in 2024. The sequential move from March at 4.3% was to +4.9% in April.

We have looked at the savings rates issues across the cycles in past commentaries (see Savings Rates: Context Across the Cycles 10-27-23). Rising savings rates are often consistent with a more defensive consumer, and we have seen ample evidence of that in “soft economic releases” such as surveys, but we also heard plenty of empirical evidence in earnings calls including some very mixed retail earnings in recent days.

The sharply revised saving rates since last month leaves saving rates low vs. the median of 6.9% but high vs. recent months. We have looked at the savings rate dynamics in earlier commentaries (see Savings Rates: Context Across the Cycles 10-27-23). Saving rates peak in times of worry (occasionally panic) as evident in the chart above. The period leading into May 1975 was no picnic while Nov 1981 and Dec 1992 had a raft of issues.

Sometimes there are anomalies during expansions such as in 1987 when the oil patch had basically crashed starting in 1986. Regional stress was high, and banks and thrifts were failing. People had to draw down savings or they saved to weather the storm. COVID and the various stimulus actions had a distorting effect on the numbers as well. The exercise is one of looking at the numbers and seeking out trend lines across the income and outlays disclosure.

Adjustments to income at the industry levels or stress in major regions can move multiple lines in what is a derived number. Radical adjustments to transfer payments tied to political tides (like the attack on Medicaid in recent legislation) could strain these numbers in 2025. The same variability is true for income lines as more workers get deported and cyclical conditions could lead to payroll pressure.

There are always multiplier effects and layers. Tariffs are not just about a border tax to pad the revenue line. The tariffs have great significance for household budgets and corporate revenues, costs, payroll and capex (including IT spending). That spills into cost-cutting actions and capital budget pauses. That is when the rule of “one man’s capex is another man’s revenue” spills into “one man’s expense line reaction is another man’s inflation” (or job loss).

See also:

1Q25 GDP 2nd Estimate: Tariff and Courthouse Waiting Game 5-29-25

Homebuilder Rankings: Volumes, Market Caps, ASPs 5-28-25

Durable Goods Apr25: Hitting an Air Pocket 5-27-25

Footnotes & Flashbacks: Credit Markets 5-27-25

Footnotes & Flashbacks: State of Yields 5-25-25

Footnotes & Flashbacks: Asset Returns 5-25-25

Mini Market Lookback: Tariff Excess N+1 5-24-25

New Home Sales April 2025: Waiting Game Does Not Help 5-23-25

Existing Home Sales April 2025: Soft but Steady 5-22-25

Credit Snapshot: Lithia Motors (LAD) 5-20-25

Home Starts April 2025: Metrics Show Wear and Tear 5-19-25

Footnotes & Flashbacks: Credit Markets 5-19-25

Industrial Production April 2025: CapUte Mixed but Time Will Tell 5-15-25