BB vs. CCC Spreads: Choose Wisely

The CCC tier is posting spreads that signal an uptick in defaults, but even a doubling of defaults will leave the HY default rates below average.

The CCC tier is posting spreads that signal an uptick in defaults, but even a doubling of defaults will leave the HY default rates below the long-term average of around 4%.

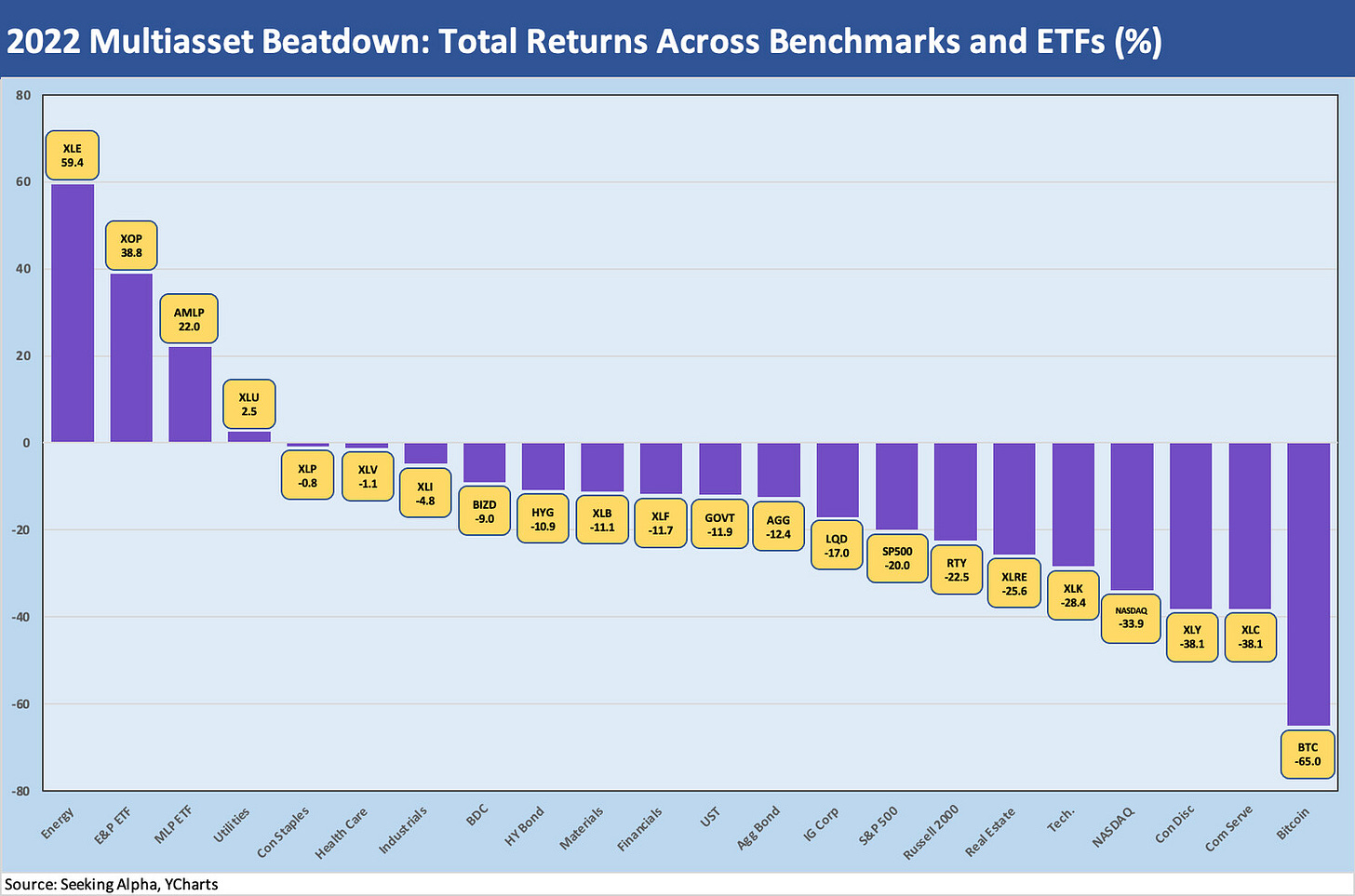

The US HY market put up its second worst total return year in history during 2022 while floating rate loans rode the front end of the curve to outperform HY bonds.

The duration hit to HY benchmarks combined with spread widening left HY with a worse performance than during some uglier years such as 2000 and 1990.

In US HY, it comes down to name picking in the end, but we look at the spread histories for the BB vs. CCC tiers and some cyclical histories for a frame of reference.

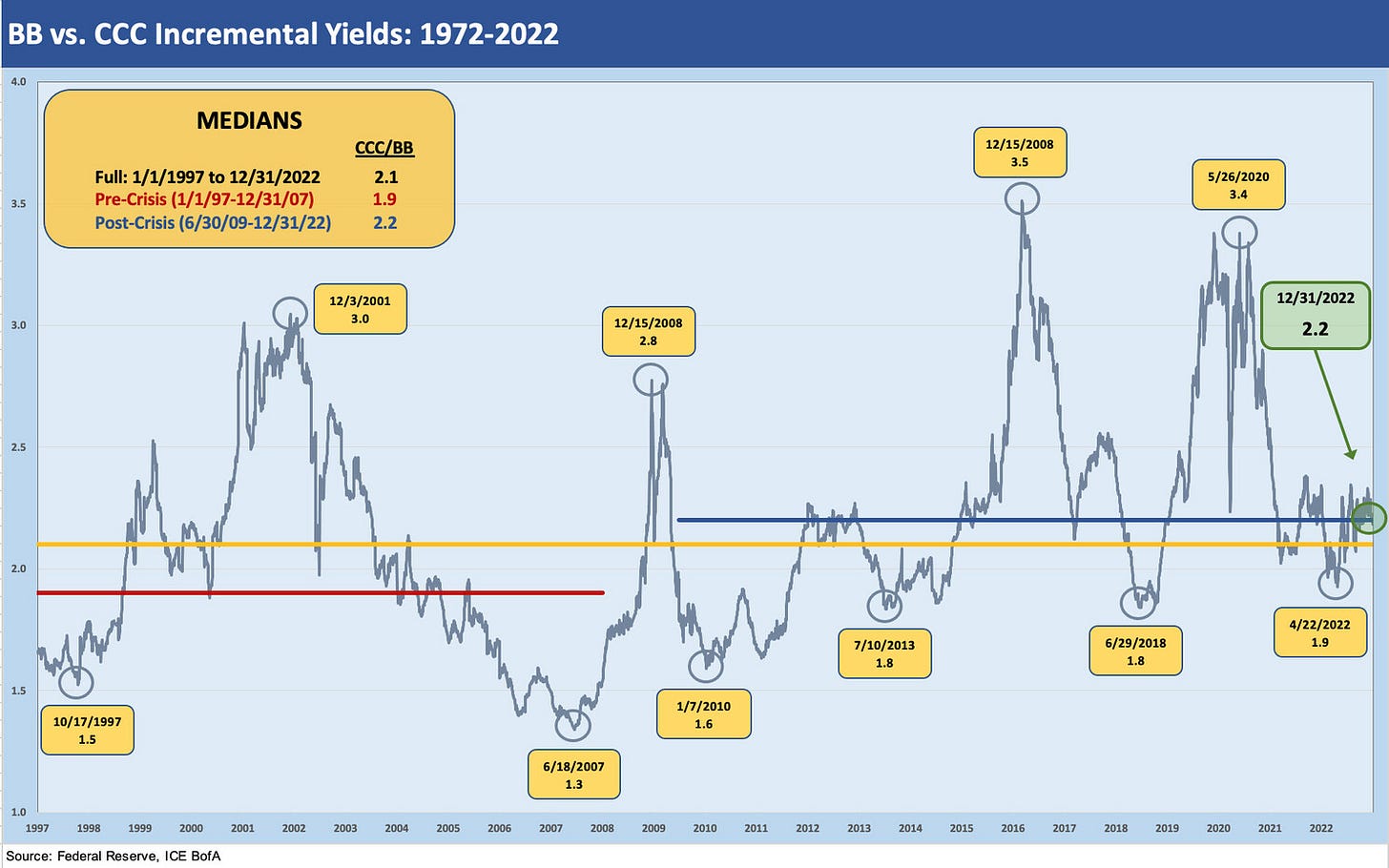

In this commentary, we look back across the cycles at the risk pricing differentials between the BB tier and the CCC tier. We look at the CCC-BB equation as somewhat of a “Hi-Lo” risk premium comparison, which can offer signals on where the market is heading when pressures such as Fed tightening start to weigh on risks. HY spreads go across periods of compression and decompression, so the BB vs. CCC spread gap provides some cyclical indicators.

The timeline, as laid out in the spread charts, underscores the volatility of HY OAS across the cycles. Those cycles have varied widely since the market was born in the 1980s. HY bonds and loans are now a maturing core asset class with leveraged finance as broadly defined becoming a bigger part of long-term planning and asset allocation in retirement funds. The rise of direct lending and private credit is part of the loan asset class evolution. Loans and HY bonds got a lift after a period of income starvation earned the credit asset subsectors more focus across the risk-return spectrum.

For some background on the word “cycles,” we should flag a few definitional liberties we take. We often distinguish between business cycles (old school macro trends and GDP patterns), credit cycles (asset quality erosion and risk repricing), underwriting cycles (Wall Street excess as we saw in TMT underwriting bubbles of the late 1990s), and default cycles (the lagging indicator as quality erodes and bad deals come home to roost). If we want to really torture the use of “cycles” we can add in monetary policy cycles (easing vs. tightening). We are at a crowded crossroads right now on all of them.

The only constant in US HY asset class across cycles is that there are always HY dogs and bouts of bad deals. The recent years of underwriting and borrowing do not stand out this time around relative to the low bar set across the decades (equity IPOs are a different story as the market has demonstrated). HY bond credit quality overall is in fact quite strong, and there were a lot of low coupons locked in during the post-COVID refi-and-extension period to help ride out the 2023 UST uncertainty ahead.

Loans and HY bonds in the 60/40 context…

Inflation and Fed tightening have reminded the market in 2022 that bonds and loans can have very different performance dynamics. More defensive structural protections and floating rates make for a broader menu of alternatives for institutional and household retirement portfolios seeking income at a given risk profile. The trends put an increasingly mature asset class (leveraged loans, loans in general, HY bonds) in the alternative mix for an old school 60/40 portfolio. The question for many is, “Do I take that risky credit asset class out of the 60 or the 40?” Since the cycle is somewhat vulnerable in 2023, taking it out of the 60% (i.e., equities) is easier to justify. Long term total return tables frame up well when you reinvest coupons. This gets back to investment time horizons.

The OAS details in these charts herein only cover the period from 1997 based on available data. The daily data before 1997 is not there to capture the Glass Steagall years of the 1990 bottom in US HY. As a reminder, that was a wild year of change that included the Drexel bankruptcy and broad Wall Street retrenchment in HY bonds. The loss of secondary liquidity does not get reflected in the index histories regardless.

The -4.4% total return in 1990 was eclipsed by the 2000 negative total return of -5.1%. That set the bar for “bad years” in US HY bonds until the -26.4% of the 2008 credit crisis period was in a world of its own. The fuse was burning across 2007 (see Wild Transition Year: The Chaos of 2007 11-1-22) until it all unraveled. The 2015 oil market crash saw a -4.6% total return for US HY followed by -2.3% in 2018 as the 4Q18 swoon hit oil, HY and equities. CCC tier names were especially abused in 4Q18. A combination of factors helped bring the Fed tightening to an end and sent the FOMC into cutting mode in 2019. The COVID return to ZIRP set the stage for fiscal and monetary support, and major repricing of HY coupons. After the 2021 rebound, the market got back to where the duration pain and inflation brought us a -10% handle US HY year for 2022.

Return divergence in 2022 for loans vs. bonds was a throwback …

The -10.6% return for the US HY index in 2022 (source: ICE) is now a very distant second in the “worst performance” bucket behind 2008, but the negative return of 2022 was 2X the magnitude of the #3 worst loss in 2000. That makes 2022 a very ugly year for HY bonds in any context. In contrast, leveraged loans rode the tightening cycle to higher coupons to go along with more defensive structural seniority (secured status, more guarantors, some additional covenant protections). Loans beat bonds by around 10%. Loans seldom outperform HY bonds across the credit cycles, but this year was the best outperformance year for loans since 1994.

For 2022, loans were in slight positive territory and could ride reasonable quality trends and a sharply rising front end of the curve. While loan benchmarks have been quoted at around breakeven on the year, some of the bellwether loan ETFs posted mid-single digit negatives. They still outperformed HY bonds and other debt by a comfortable margin.

The solid win by loans vs. bonds hearkens back to an estimated 11% area outperformance for loans in the long-ago year of 1994, which is high on the list of unusual Fed tightening years. That was an early cycle year (the recession trough was March 1991). The surprisingly aggressive and repeated tightening by the Fed and material upward shift of the UST curve saw duration hammer bonds and rattle equities (see Bear Flattener: Today vs. 1994 and Aftermath 10-18-22). That 1994 year of HY bond performance weakness was followed by a monster rally in risk from equities to HY with 1995 the best S&P 500 year of that bull market decade.

We saw a similar magnitude of outperformance of loans over bonds in 2000 on the basis that HY bonds were crushed so badly in the TMT aftermath in an extended default cycle. As we head into 2023, the cyclical longevity question mark looms over credit in a way that it did not in 1994. In contrast to 2000, we are not in a deal quality and HY credit cycle freefall. The moving parts of the Fed, the yield curve, and the economic cycle remain very much debating points. For the first half of 2023, we see loans as a safer home since our baseline view is for a soft landing even it qualifies as a 2001-style recession (see How do you like your landing? Hard or Soft Part 1, Part 2, Part 3). We expect the Fed to hold the line, but the cyclical symmetry is still more of a question.

Finding a transmission mechanism for major industry stress is a challenge…

Part 2 of the “How do you Like your landing?” series looks back at the cyclical downturns and the key GDP lines. The past and prologue compare-and-contrast make it hard to see which major issuing sectors could really move the needle in 2023 in credit stress in relative terms vs. those past cycles.

You need to “pick a line” in the GDP accounts that contract materially. We don’t see it in PCE even if the fixed asset line has some very vulnerable spots in Residential and in Structures. Equipment has been hanging tough vs. past plunges. We have a hard time coming up with a dire scenario with a healthy bank system and a resurgent appetite for income that is now available in credit. The absence of an overwhelming negative story line at the business cycle level or in the credit cycle dynamics to satisfy the bears offers some comfort.

Just a few examples of major industries worth considering:

Housing and Homebuilders: Housing is a mess, but the mortgage rate climb will moderate and positive equity for legacy homeowners has an enormous cushion with a lot of low coupon mortgages locked in. Those YoY housing statistics will and can keep heading south, but 3% to 4% inflation by the end of 2023 would make it temporary. In the meantime, the homes under construction in single family and multifamily are very high and support robust economic activity (see Market Menagerie: Home Starts – Will Housing Nerves Infect Multifamily? 12-21-22). We just saw more jobs added to Residential construction in the past week’s jobs report. Homebuilders are not a major sector on the low end of HY (BB and BBB heavy) but they have very strong cash flow characteristics with their variable cost structures.

Autos and Related Services: The Auto OEMs were already at recession level volumes in historical context in 2021-2022. Chips have been a production killer and that has spilled over into 2023. An important factor is that the industry is leaner and healthier that at any cyclical turn of the past 40 years (excluding COVID 2-month recession). We note that the credit crisis and OEM bankruptcy backdrop for the OEMs in 2008-2009 was an extreme anomaly at 9-handle SAAR rates and the ensuing Chapter 11 process. The OEMs suppliers still face some long tail challenges from the China geopolitical connection and European recession, but the suppliers will not move the macro needle in the face of a strong US consumer sector. The auto lenders and used car players face some headwinds, but that is for another day. Rising subprime losses is not a major cyclical risk factor. It is an earnings problem for some lenders.

Energy and Energy Transition: Energy is a very important HY sector and the same is true in the enormous BBB tier. Upstream, Midstream and Downstream are rolling along in credit quality and would still be stable even at $60-$70 oil. The Midstream is in heavy free cash flow generation mode after years of debt-funded capex and M&A. Energy transition topics are a. major area of focus in the capex picture in Energy. This is also the case in Autos on the breakneck pace of EV investments. Spending in Defense and Aerospace is also picking up in areas such as alterative propulsion (electric, hydrogen) and urban air transport. That takes spending and investment on the Fixed Asset lines of GDP.

Health Care: HY healthcare bankruptcies dominated as a 2022 topic. The broader healthcare sector across all goods and services is around 18% to 19% of GDP, but the handful of problem names and legal liability risk in US HY are more isolated this year than last year (e.g., Endo). The vast majority of health care credit is in IG. The secular trends at the macro level for health care calls for slow and steady growth and sustained hiring on high labor demand. There is no chance of a major rollback in Obamacare with the current political lineup in Washington.

Services: “Services” is a category in the bond index that does not reflect the scale of what services means in the Census or BLS. Services in the HY and IG index “put the hodge in podge” with respect to industry mix. Services broadly have a running start in 2023 of a 50-year low in unemployment, a growing population, and a highly diverse and resilient range of line items in the narrow industry profiles from mobility to equipment rental to waste management, among others. The tailwind overall is demand, and Services inflation is one of the bigger problems the Fed faces in fighting inflation. Services needs to be taken one major subsector at a time for analysis as the year proceeds.

Defense and Aerospace: The airline industry is seeing very strong demand, and that drives some good news on customer health and aftermarket services/parts demand. Boeing has finally had some good news, but BA remains under pressure with Airbus clearly winning on the commercial side. The defense budget will go higher, the new weapons systems are raising the bar in a very tense world, satellites and rocket technologies (hypersonic, space, etc.) are demanding more investment for national security as well as commercial applications (the lines blur at times). We assume the semi-housebroken segment of the GOP (we hope under 10% of the party) is not going to create a budget crisis and default brinkmanship that hammers defense spending or derails Ukraine aid. That said, it will take a while. Attacking defense even by accident would be political idiocy for the GOP and would likely be just a narrow group of the usual fringe freaks. (Then again, we are in a new world).

Bottom line on credit and risk trends in pricing…

The performance of 2022 has given investors much to ponder from small to large. In a testament to what Fed tightening can do to performance by old school bond math, bonds were crushed alongside equities this year (see Multiasset Beatdown 12-31-22). US HY fundamentals were much stronger on average than during earlier negative return years, the issuer quality mix was higher (the high BB tier index share of almost half), and the industry concentration was better (e.g., a high energy mix in a bullish year for E&P financial health). So much for the value of diversification of risks in 2022. Those who toggled across bonds and equities did not see their risk mitigation strategy work too well.

The market now sees an uptick in bankruptcy volume ahead. As we detail in the charts and discussion, the CCC vs. BB pricing differential and spread decompression trends on the low end highlight the growing divide in risk pricing between the BB and CCC tier.

Spread peaks, troughs, and medians…

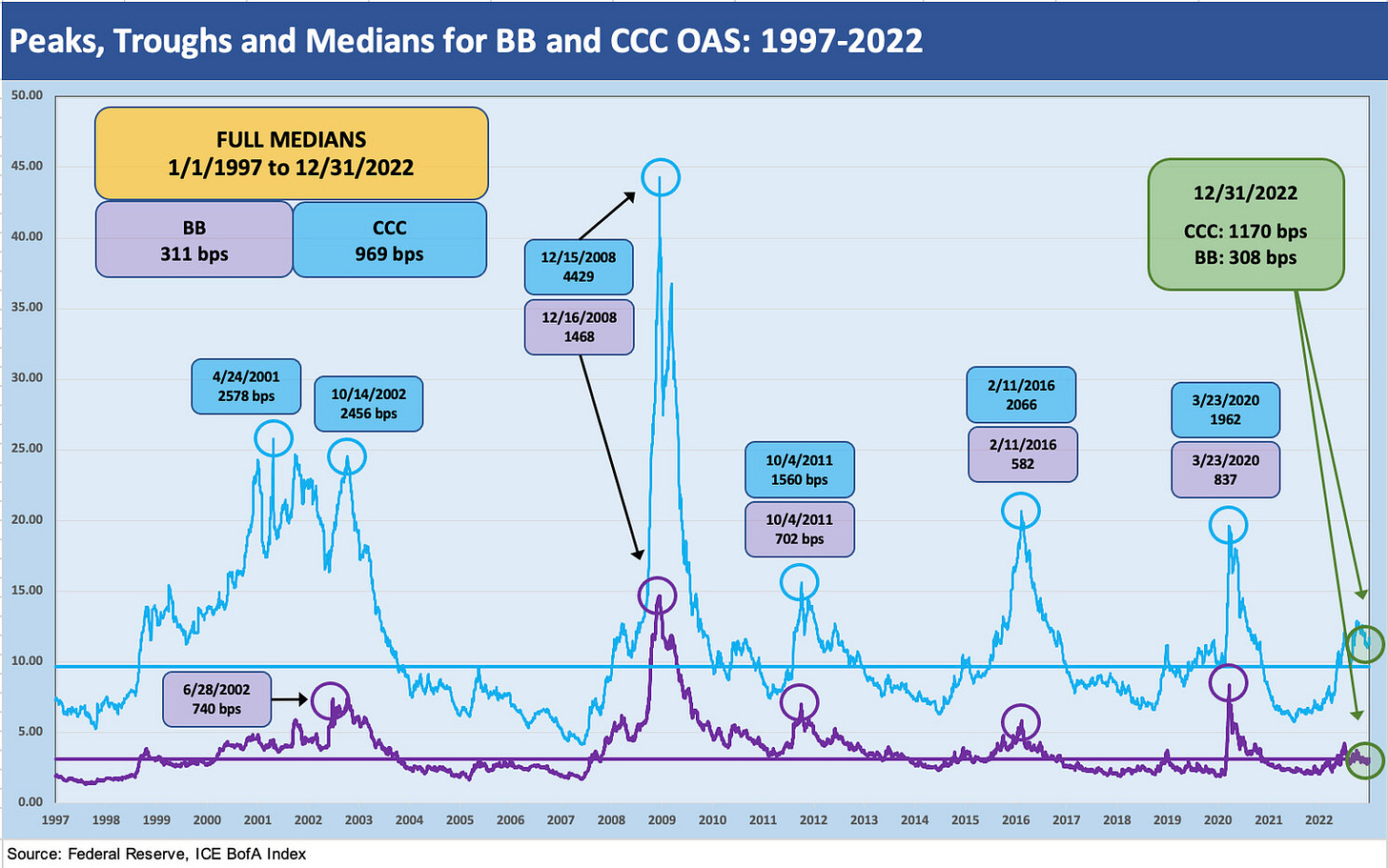

The chart at the top of this commentary highlights the cyclical highs and lows for BB and CCC tier OAS across the TMT bubble bursting in 2001, the credit crisis of late 2008, systemic sovereign wave (Oct 2011 peak), the oil market crash (Feb 2016 peak), and the COVID wave (March 2020 peak). We also break out the long-term median.

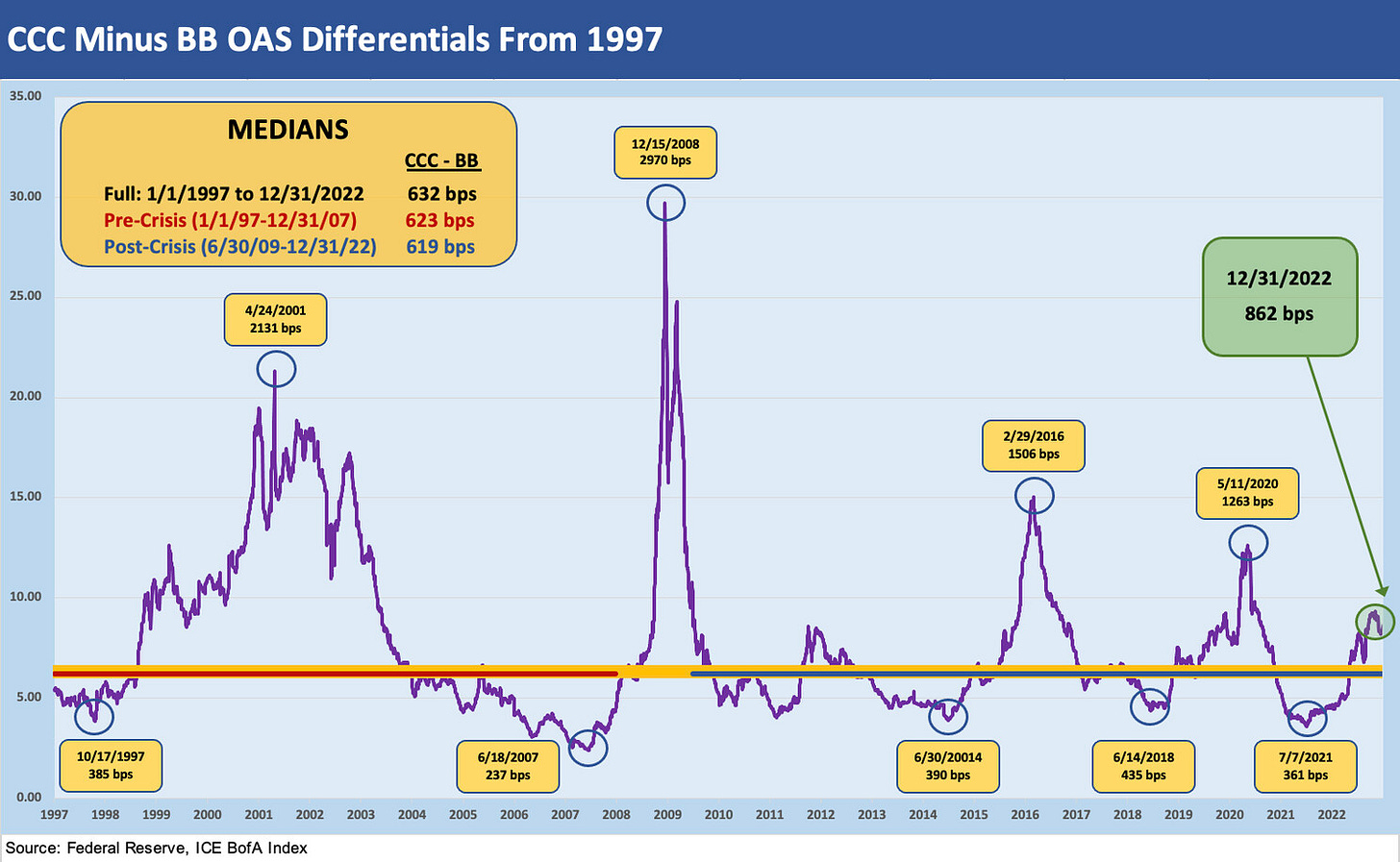

The exercise is simply to plot CCC index OAS minus BB index OAS. We plot the cyclical tights in these “Hi-Lo quality spreads” along the bottom of the chart (immediately above). We see lows for Oct 1997, June 2007, June 2014, June 2018, and July 2021. The risk premium differential peaks are found in April 2001, Dec 2008, Feb 2016, and May 2020.

The long-term median differential is a +632 bps pickup from BB to CCC. June 2007 was a compression story in US HY quality spreads that soon gave way to a state of suspended animation in the summer as the crisis conditions started to surface, some early warning hedge fund blowups unfolded, Bear Stearns management was in crisis, and Countrywide was scrambling to raise capital and find a buyer. The cycle peaked in Dec 2007 (a year later that date was set by NBER, see Business Cycles: The Recession Dating Game).

The short history on spread spikes follows…

We always find a quick memory jogger useful in framing the events and backdrop of the spread peaks:

The TMT cycle and 2001 peak: The TMT years and its underwriting practices were so bad that the regulatory and legal response generated a lot of change. From Sarbanes-Oxley to the Global Research Settlement, the government and its enforcement agencies cracked down with Enron (2001) and WorldCom (2002) as the headline acts. Internet stocks hit equity markets while debt-funded Telecom and Media capex dominated the problems in US HY.

The default rates started to climb in late 1999 after 1998 had already brought EM contagion (Russia default) and the LTCM counterparty crisis. Wild times in the default cycle of 2001-2002 saw a double dip default and HY spread wave. The summer of 2002 was the noisiest all the way up to the BB-BBB divide as some fallen angels plunged into BB tier with some “passing go” and not looking back all the way down to Chapter 11 (notably Enron and WorldCom).

The 2001 default wave saw a diverse mix of issuers across industries including fallen angel utilities (PG&E, SoCal Edison), Enron, Asian issuers of US HY bonds, and finance companies (FINOVA) among others, so the default wave was about more than TMT. Despite the diversity of headline “filers,” the range and size of TMT issuers was so large that the TMT label captures the flavor of the period. In the end, the sustained stress shows the CCC tier spread spike being a multi-year event as issuers kept on crashing from the late 1990s until late 2002.

The credit crisis of 2008: The events surrounding Lehman and the AIG bailout are landmark turning points that we discuss in other histories, but the main distinction in the 2008 spread spike was the systemic bank risk element. When issuers are weak to start with and industries under extreme stress, when bullish forecasts become viewed as fee-driven banker hallucinations, when quant models highlight that the triple-jointed quant inmates took over the asylum, then confidence is shattered. Risk aversion spikes and the correlation of risky assets heads towards 1.

With banks lined up like counterparty dominoes on hedging and speculative, leveraged use of derivatives (e.g., CDS), the need for banks in crisis to preserve liquidity and take minimal risk causes secondary cash market liquidity to evaporate. That is when credit contraction can go from very bad to worse.

As notable examples, the inability to sustain asset backed commercial paper markets, the fear of a collateral unwind for the ages, the worry that bank lines might not be able to get drawn (and the same for consumer credit card lines), and the potential for waves of suspended fund redemptions were setting the stage for much worse without government action. Bush and Obama both understood the risks.

In later years (and now), the ideological gnomes like to cite the “bailing out Wall Street” catchphrase, but the reality in late 2008-2009 was that Wall Street and Main Street faced the same fate. Systemic liquidity and asset values from homes to loans to bonds all had a gun aimed their collective heads. If you want to say the major banks had Main Street as a human shield, use that metaphor. That one has more merit than the inference of a narrow special interest bailout of banks.

Failed banks, no credit lines, companies not supported by adequate liquidity, collateral implosion (notably in financial assets) and waves of consumer and corporate defaults is about more than Wall Street. Credit card lines would be canceled if undrawn, and then those with balances would face a default decision on what was drawn (i.e., “If the bank cancelled my line, screw them…”). Consumer finance and ABS would be toast. There are no political points in stating all that in 2023.

The real economy was very much swept up in the crisis. Auto OEM and supplier chain bankruptcies were accelerating on the consumer sector collapse and the plunge in auto SAAR rates to 9-handles. Production chains could come to a stop in the absence of trade credit. The multiplier effects cuts both ways.

Dealer auto credit was also going to get much tighter if the captive finance companies could not fund buyers and dealers. Rental fleets needed the ABS market for their millions of fleet vehicles. The question of wholesale dealer funding was also a major question, and it is tough to buy cars even for cash at an empty lot. The ability to meet warranty claims would be in question. The customer could not buy a car with retail finance losing access to a viable securitization market.

The same in housing? Who was going to buy the whole loans on a mortgage? How would those loans get securitized? In other words, the “bum on Wall Street” needed help to make the Main Street dealer viable or to allow mortgage finance to function across the suburban, exurban, and rural markets. Anyone want to talk food chain? Funding and hedging the commodity cycles? Counterparty credit lines? The beat goes on…

Our point in that semi-rant is the continued revisionism on the credit crisis of 2008-2009 (usually by Democrats in the House or Senate) ignore the interconnections and multiplier effects in the “Wall Street bailout.” The “let the market work” elevator music (usually from the GOP players in the House or Senate) is also conceptually and factually lite, but it at least has the merit of brevity. In the end, being politically savvy and prudently opportunistic while being conceptually and factually ignorant is a lifestyle decision.

The sovereign systemic wave of 2011: This one is another macro top-down risk aversion threat that played out with the 2008-2009 trauma fresh in the minds of market participants. The wave of spread widening was more about fear of macro events infecting bank systems again. IG banks were hammered during this stretch. As discussed above on the 2008-2009 crisis, the anxiety was tied to sovereign stress with a transmission mechanism to credit contraction and risk aversion. If an investor sees a sovereign problem, then the investor worries about banks. If you worry about banks, you worry about corporate sector financial conditions and recessions. That hit borrowers and equities in markets at the issuer level. You worry about secondary liquidity for bonds and bank line terms getting tightened. This set off the logical response in spreads.

In the sovereign realm, the 2010 warmup had Greece as a proxy for the bigger Eurozone stress picture. (“If Greece, then Spain. If Spain, then Italy,” etc.) Ireland seemed like less of a worry at the time (the Irish do austerity well). The summer of 2011 was the main event for stress flashbacks since the focus had turned more to Spain and Italy. Meanwhile, the US downgrades and lunatics in Congress rationalizing a US default (it was more than brinkmanship) made the US downgrade a headline many could not get their arms around.

The irony was the UST market rallied dramatically (not the usual response with a threatened default), underscoring the conviction that the US was a AAA even if just on where to invest during panics. The hope is that this holds up in 2023 as a fresh crop of deep thinkers in Congress might threaten default again. This is a topic that will come up in 2023. Then everyone can revisit whether the constitution allows the US Treasury to pay the debt and issue more bonds without Congress in order to avoid default. That debate can be dusted off. It is not a new one and has fortunately never been tested.

The late 2015/early 2016 oil crisis: The steep sell-off in US HY during early 2016 offered fresh reminders of the US HY market dynamics. Secondary liquidity is not deep, and the number of market makers is smaller than it has been with record sized markets. The 2008 systemic crisis took some major brokers out of the picture and merged a lot of banks as well. That means less capital in the market for trading. Many US regional banks in the HY origination picture have also stopped making markets since then. Meanwhile, HY is still heavily wagged by open end mutual funds and the related redemption risks on that side of the supply-demand equation.

That is a topic we have written about in prior lives, but the main risk is that everyone sees that fund redemptions means “bids wanted.” When events do occur such as the largest issuing sector (Oil & Gas in Jan-Feb 2016) facing extreme stress, secondary pricing reacts quickly on redemption fears. As we saw in late 2015, that reprices investment alternatives, and the decompression wave comes. This took 2015 HY total returns into the negative zone on the way to a Feb 2016 spread peak (2-11-16).

The bottom tick in the US HY index on 2-11-16 was 83 cents and a 10% area yield to worst. The Energy sector had dropped all the way to a 52-area price. The E&P segment with its B tier composite rating went all the way to 38 cents on the dollar and 2900+ bps in spread and 30% yield. The CCC tier overall was at a 58 cents price and a 21% handle yield. That all occurred during an economic expansion.

There are home runs to be had when pricing reflects such a disproportionately high secondary liquidity penalty that is not in line with the default and loss exposure. In the case of E&P, however, there were bankruptcies on the screen that highlighted single digit unsecured recovery rates, and that made it an exercise for the very hearty. There are plenty of those types in the business. The price volatility and theoretical downside also offered issuers a lot of negotiating power in coercive exchanges.

The COVID spread wave of 2020: The COVID damage was a very short-lived recession (2 months) and the rapid action of the Fed, UST, and Congress soothed a lot of nerves. The markets were such that panic selling was less evident since the banks were also much healthier and clearly had ample alternatives and support from the arsenal quickly laid out by the Fed and UST. Once the refi/extend window opened up, the tangible demonstration of credit market access relieved a lot of worries. The Nov 9, 2020 vaccine news then sent the credit and equity markets off to the races.

What do the current spread and yield differentials tell us?

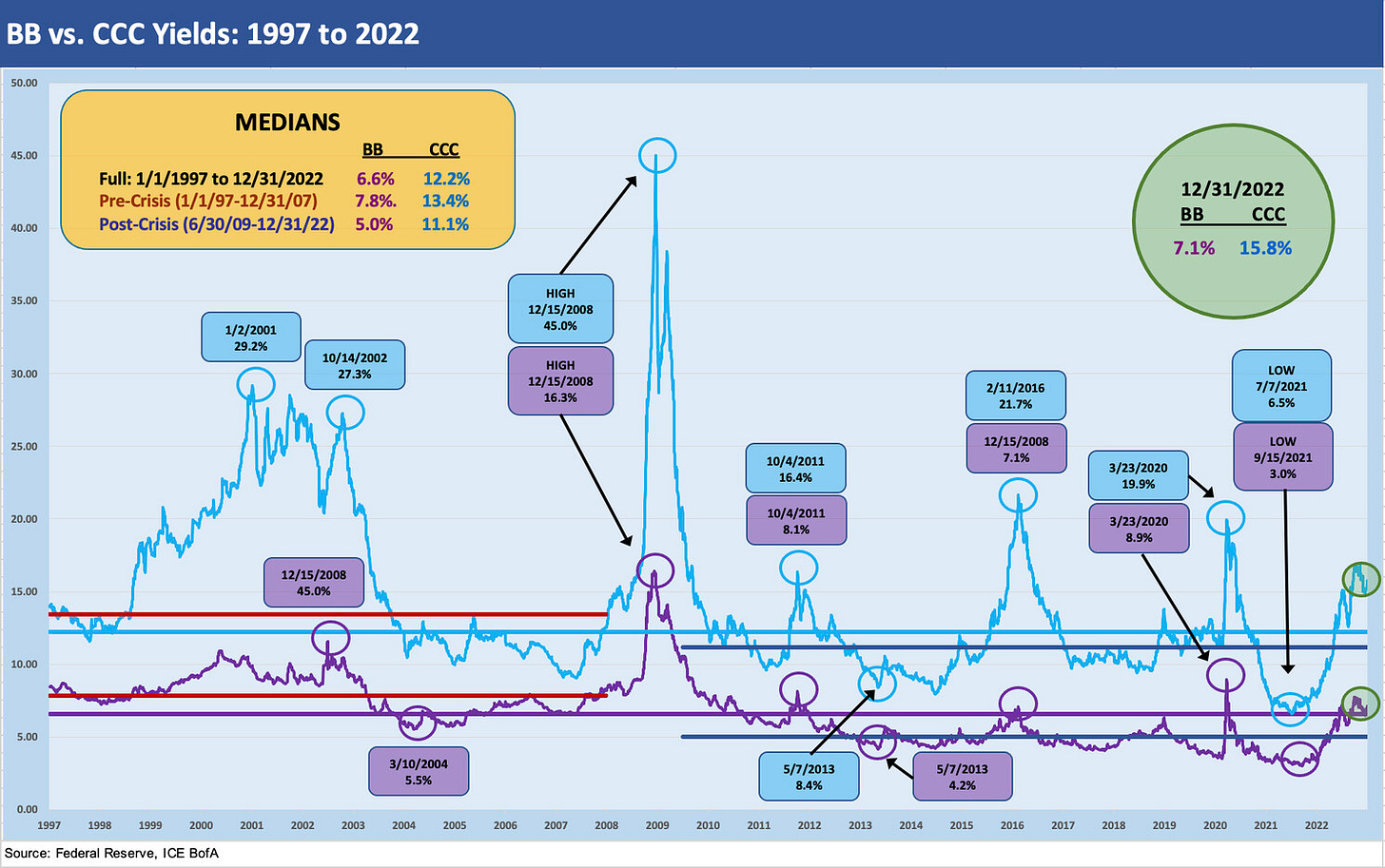

As highlighted in the median details in the earlier spread charts, the BB tier is hanging around the median (long term median of 311 bps, 2022 ended +308 bps). The CCC tier is wider than the median (+969 bps) to end 2022 (CCC at +1170 bps). The earlier spread chart plots how those spreads flow into a yield curve that rose materially across 2022. The yields and spreads work in tandem to generate an all-new expected return discussion. One can easily make the conceptual case that CCC bonds should generally be framed against expected returns for equities and not bonds. In contrast, BB bonds can be viewed as more bond-like and have a different risk expectations checklist.

In the yield chart above, we plotted the medians for US HY BB and US HY CCC tier yields across the cycles starting back in 1997. The long-term median is 6.6% on the BB tier vs. 12.2% on the CCC tier. We also break out the medians into a 1997-2007 segment (median for BB 7.8%, CCC 13.4%) and a post-crisis segment from the June 2009 recession trough to year-end 2022 (median for BB: 5.0%, CCC: 11.1%). We see BB tier yield lows in March 2004 and May 2013 and a 3.0% handle in Sept 2021.

At a 15.8% yield to end 2022, the CCC tier is offering yields that are well above the long-term return on equities. That is where the lure can end up as a painful hook. The issuer selection exercise gets back to the old adage of “buy CCCs that are CCCs because of capital structure and layers and not weak operating profiles and inadequate cash flow.” That is where adage #2 comes in: “Everything is AAA at a price.” That is the somewhat obvious case of “choose wisely” as we see in the title of this commentary.

The BB tier, at a 7% handle to end the year, has more of a value story to work with if one is defensive on fundamental risk and more bearish on the direction of the credit cycle and default/recovery expectations. That is a better risk-reward area to shop for now. That includes for US IG investors stepping down. A weaker economy can do some damage to BBB names with a full yield curve and relative shortage of natural long bond buyers on BBB corporate bond downgrades. There is always an issuer decision to make in every market whether at the speculative grade divide or in CCCs.

The Hi-Lo risk challenge…

At this point, we see US IG bonds outperforming US HY in excess return in 2023, but there are more positive cases to make for the IG market (and to lesser extent the BB tier) bringing a better risk-reward on duration. That duration edge was not the case in 2022 with IG being the worst performance among the debt comps. Like any other risky security, the exercise still has to get back into the industry level and issuer story. After a year when Healthcare and legal risks dominated the default ranks in US HY by dollar value, the stories in 2023 will run the gamut on relative risk profiles.

While it might be taking some liberties, it is safe to call the BB tier a medium level risk tier (BBB and BB) and the CCC tier a very high-risk market. The BB averages default rates at a fraction of 1% per year. In contrast, the CCC market shows up in the risk-adjusted return analysis over the years in a very unfavorable light when Sharpe Ratios get factored in. The BB and BBB tiers turn in solid comparative metrics vs. B and CCC across the decades. Default rates rise exponentially (literally) in the move from BB to B. Then the exponential rate increases again in the move from B to CCC.

These relative risk numbers can move around based on time horizon and can have all kinds of distortion in issuers and industry mix and cyclical timing in measurement. The safe statement is that a par level on the CCC composite (a rare event for the CCC index) has very unfavorable risk-reward symmetry. High leverage and high earnings volatility in rapidly changing industries or asset-lite services operations can make for tough recovery stories. Not every CCC of bygone years can be a TransDigm or HD Supply.

As we framed in spreads above, the CCC tier is much more volatile in spreads and thus in yields as well. In credit market downturns, quoting CCCs on a dollar price basis rather than spread is common for a range of reasons as CCCs present a risk profile more akin to equities. The expected return for a given time horizon is the more appropriate conceptual framework.

We discussed the related market developments across the timeline earlier in the quality spreads section. The yield timeline can get distorted by a materially reshaped and shifting UST across time. Much of the all-in yield in the aftermath of the credit crisis was comprised of spreads with the UST market so low. 5-year UST bonds under 1% make for unusual markets.

Long ago in the early years of US HY, seeing a coupon in the mid-teens was a normal day. After all, the late 1980s saw 8% 90-day T-bills. The move up into mid-teen yields (or much higher in some CCC periods along the way) shows the proxy for expected returns being more equity like. This is where the risk-reward continuum comes into play. The CCC tier is like an allocation to equities – except this “equity” has a coupon.

The BB tier is a major factor that blurs the IG vs. HY lines…

The size of the BB tier in absolute terms is such that the investor base for BBs is as much an IG market as a speculative grade market. Meanwhile, the BBB tier is larger than the GDP of many major nations. That has made for a very large midsection along the credit spectrum with a lot more demand generated over the years on reach for yield from income-starved IG investors. Many “IG funds” and pension managers adjusted their criteria to better reflect the mix of the market and the much lower relative risks associated with the BB tier. That “junk” brush (more like a roller) is still seen in many pockets of equity market commentary. We update the BB vs. BBB divide in a separate commentary.

Apart from the wide swings in the BB tiers and off-the-charts spikes in spreads and yields seen in the CCC tier, the main takeaway is that each cycle had their own distinctive mix of key risk drivers for the BB and CCC tiers. The expected rise of defaults and waves of spread decompression in 2023-2024 will have its own unique menu of factors. We have not had a stagflation or high inflation backdrop in the modern HY bond era since the double dip recession of 1980-1982. I started in the Private Placement area of Prudential in early 1984 when the insurance companies (along with names such as GE and Westinghouse among others) ruled the roost in LBO land. They had plenty of defaulted/restructured credits in the private portfolio from the painful downturn of 1980-1982, but the public HY bond market as we know it was just getting ramped up. The HY market changed at a dramatic pace as private equity firms and sell side merchant banking units in the securities firms seized the reins. The HY bond market changed the game, and the rest was history.

For the modeling mavens out there forecasting defaults, we emphasize that the actuarial history of HY credit cycles is really only four cycles: the 1980s LBO binge in the Glass Steagall years, the 1990s convergence of banks and brokers and the TMT wave, the 2000s structured credit and housing bubble, and finally COVID. You could argue that COVID was not a real cycle, and the credit cycle count is really three plus one pandemic. Whether top-down or bottom-up, each of those periods were very different.

Spread and yield decompression is entering that cyclical stage…

The expansion of quality spreads usually will reverberate from the bottom up as the HY market prices in rising risks of default, the threat of tight credit conditions worsening, higher refinancing risk for those facing high maturity schedules, and the inevitability of more defensive market making in an Over-the-Counter (OTC) market in the second age of Volcker (restrictions on prop trading). While some will engage in “enhanced market making” and get around some of the so-called rules, the days of brokers tag-teaming their financing business/trading desks with hedge fund “partners” is gone. That further impairs secondary liquidity risks on the low end in distressed names and creates even better opportunities for value seekers in that end of the spectrum. This gets into the fear of the “bottomless CCC” in the risk-reward equation.

The OTC HY bond market is handled by fewer market makers than at any time in history. That smaller market making funnel comes at a time when there is record AUM in the leveraged finance market and even more so when one factors in private credit and the rise of the small and midcap loan segment in the expanding world of BDCs.

Secondary liquidity risks will get tested once again as the market keeps on growing in risky credit and especially if the hard landing scenario plays out. As we discussed herein, we are in the soft-landing school on strong jobs, a reasonably healthy consumer sector, better YoY inflation math ahead, and the lack of a path to major industry level stress. There are no shortages of extreme event scenarios in the risky asset markets and those cannot be ignored (European sovereign and bank system risk, China-Taiwan, US budget risks, etc.). It comes down to staying diligent.

For one last chart, we look at relative yields. Using a simple ratio of yields across time for CCC/BB can show how the relationship moves across the credit cycles. The basic foundational concept of “more risk needs more expected return” is reflected in this basic ratio.

As noted on the chart, the long-term median is around 2.1X with the 1997-2007 period median at 1.9X and the post-recession trough period after June 2009 at 2.2X. That 2.2 level is right where the year ended. The ratio is likely to be biased higher in 2023 on rising default risk and weakening economic fundamentals. A strong backdrop in energy and relatively healthy consumer sector (50-year lows in unemployment) will mitigate more extreme spread moves. That said, the range of long tail outcomes do not lack transparency even if the odds are long (see Risk Trends: The Neurotic’s Checklist 12-11-22).

We see lows in Oct 1997 (the HY market spread lows) and June 2007 (the cyclical spread lows for US HY) among two periods of extraordinarily low risk premiums and credit excess. Early 2010 was in the period of ZIRP and as defaults were cleansing the HY market and taking the worst of the issuers from the index on the usual lagging default effect. As a reminder, issuers quickly drop out of the index as they default. After rebalancing of the index, the CCC and below spreads can contract.

The 2013 period was a new issue boom for CCC tier credits in what was a major risk rally in US HY after the sovereign crisis was dialed back. The 2013 year was also a high point for the S&P 500 in the stretch of years after the crisis. Banks were roaring back in the second half of 2012 and into 2013 as the UST curve steepened and systemic fears waned. That UST steepening can also distort the relationship between the longer duration BB tier and the shorter duration CCC tier.

The main takeaway is that the yield relationship of the CCC vs. BB tier is hanging around the median currently. The spread relationship is moving above the median and will likely keep moving higher away from the median further into 2023, even if we have an early year rally. The CCC tier is always a name picking exercise with the best values found when the volatility is higher, the market more nervous, and the liquidity premium more material in scale. The CCC tier is not there yet vs. history.

See also:

The Speculative Grade Divide: BBB vs. BB Differentials 11-22-22

Credit Allocation Decisions: Fish Selectively, Stay Above Water 11-14-22

Old Time Risk: HY Season Faces Challenges 11-7-22