Old Time Risk: HY Season Faces Challenge

We look across the cycles at HY spreads and vs. 5Y UST. HY is hanging around the median area, which is a dubious value.

Very Short Form

After a brutal 2022 for total return in risky assets, investors and street research will soon be working on their asset class outlooks for next year. There is much to consider heading into 2023. In this commentary, I frame some asset class returns in an ugly year for any kind of risk – equity, credit, or duration. I then look at the history of relative yields for the US HY index vs. the UST market. I look at them in absolute terms and then in relationship to one another (“relative yields”). Next, I frame historical spreads for US HY in absolute terms and relative to the risk-free alternative, using the 5Y UST for its relative proximity in duration to the HY index.

The extraordinary swings we see in these HY charts are a reminder of the unfavorable risk symmetry in US HY during periods of macro shocks or credit volatility. Those periodic gaps in market pricing underscore that time horizons matter, and a firm grasp on relative risk is crucial for such higher risk income products. Spread decompression waves have victims.

The US HY asset class has a history of being an income product first and foremost (the trick is finding fair value for the risks assumed at any given time). As history has shown, US HY stops being debt-like risk at times and behaves more like a high-risk “coupon bearing” equity. Opportunities arise when valuations get disconnected from fundamental risks or default risk. Mainstream HY issuers in the B and CCC tier can often offer expected returns well in excess of historical returns on equity and they come with cash-on-cash returns (coupons) in addition to price return. Those periods present the best opportunity to add exposure. My own view is some of those opportunities lie ahead but they are not there now.

_________________________________________________________________________

The high yield market beckons, but it is not loud enough yet…

After so many years of brutally low yields in credit, the headline yield for US HY is enticing. The problem is handicapping the more extreme outlying risks and taking those into account. The cyclical moving parts do not paint a great risk-reward symmetry for risky credit at this point. I am not risk averse on the credit cycle nor do I see a direct transmission mechanism to average levels default rates in 2023.That said, I do not see the wind-down to 2022 as a “median risk” market. The current pricing (spreads) in the US HY market is hovering around the median type levels seen in economic expansion periods. I explore that further below. To be clear, I still see floating rate loans and defensive structures (secured leveraged loans) as the better deal in this market.

Shining Some Light On US HY With Some Variables To Ponder…

I highlight a few questions to ponder as we look back across the cycle for US HY and consider what lies dead ahead in terms of risk of material repricing in 2023:

As the market looks back across time at US HY, how should we interpret the extreme swings in US HY and what that history means for the symmetry of risk ahead?

With par-weighted coupons now below the 6% threshold and the gap with cash and 3M UST returns closing fast, is the value-for-risk getting wrung out of the HY bond asset class? Is the best plan to shift to loans for 2023 for a more defensive structure?

Given the tightening of cash returns vs. legacy coupons, does the lower opportunity cost of foregone coupons encourage less asset-class-constrained investors to stay defensive in credit risk and move into cash until we get more transparency on the macro and industry level variables?

Is there a consensus around the idea that the UST market is now a 4% market, and the big pause is coming?

With the uncertainty at the micro industry and issuer level ahead, is a median level risk premium in historical context a fair value?

How should we factor in the overlay of the macro backdrop of monetary policy, recession risk, geopolitics, and critical wildcards such as oil and gas prices?

With Energy as the #1 sector in US HY and Russia and OPEC pressuring supply, how should we frame the upstream E&P risk into the HY market view whether on redemption risks and outflows or in terms of the relative recession risk of the industry mix?

Will HY still be more about industry and credit tier weighting? Is the HY lite, BB heavy strategy the way to go until the inflation and geopolitical moving parts clear up?

How do we factor in recession fears into fundamental credit trends and duration effects in US HY when everything on the macro side seems to be moving in the wrong direction?

Risk Has Not Received Much Reward of Late…

“Higher expected returns for taking higher risk” is the old-time refrain in investing. The returns in 2022 certainly have not met that standard. The table below breaks out trailing total returns for a cross-section of debt ETF asset classes including UST, IG bonds, HY bonds, and EM Sovereign bonds. I also drop in the S&P 500 broad market benchmarks along with the NASDAQ and Russell 2000 small caps. The YTD returns in 2022 and the trailing year are all painfully in the red with double-digit negatives. Growth stocks and late 2021 IPOs were slaughtered, risky credit was beaten up, and duration was seriously abused.

I include a HY ETF (HYG) on the list as a proxy for the relative returns on US HY. Using a HY ETF comes with the asterisk that it is generally a larger more liquid issuer base in the mix and does not have the full yield and higher par weighted coupons of the broader benchmark indexes in US HY. Using HYG is just a snapshot for ease of comparison across other asset class proxies, but it gets the job done.

Many investors in wealth management take their HY and IG Corporate exposure through ETFs, so I like using those in return metrics. To add to the confusion, one can scan US HY yield metrics and find quoted yields over 9% for the total index, SEC 30-day yields at mutual funds in the high 7% range, and HY mutual fund distribution yields in the 6% range. With treasuries and spreads moving around, those all-in yields are also constantly moving. The HYG dividend yield quoted on the screen today was 5.2% (11-7-22). That is well below HY index yields but also well above 1% handle S&P 500 dividend yields.

Where the HY Market Stands…

Below I plot historical yields for the ICE HY index vs. the 5Y UST. I follow that chart with a look at the ratio of HY vs. 5Y UST. I then wrap with a chart looking at spreads and spreads as a % 5Y UST for another angle. As a reminder to those who don’t typically look at credit, the spread is essentially the risk premium over the risk-free assets.

In the chart, I highlight the key “events” along the timeline in very abbreviated fashion (TMT, oil crash, credit crisis, COVID, etc.) I detailed the expansions (see Expansion Checklist: Recoveries Lined Up by Height), recessions (see Business Cycles: The Recession Dating Game), and credit cycles (see UST Curve History: Credit Cycle Peaks) in earlier commentaries already. In this exercise, I will zero in in the data presented here and avoid too much injection of event histories.

For the charts, I use the Federal Reserve and the FRED database (St. Louis Fed). The above includes the ICE BofA HY index and 5Y constant treasury. We cover the timeline from the start of 1997 to the beginning of Nov 2022.

Key Takeaways…

Expected returns vs. risks taken: An important factor in looking at US HY is that the index does not adjust for quality mix (BB, B, CCC) or changes over time in industry mix. For example, the HY index had seen a radical shift in TMT concentration from the late 1990s to the shale boom with a soaring base of E&P issuers in the HY mix.

The US HY market has higher quality credit quality mix now with around half the index in the BB tier. The crisis years and recession saw large cap Blue Chip names downgraded on the supply side and much more institutional demand for BB bonds from traditional IG funds. Being a BB does not create material barriers for many issuers. With so much refinancing already done, many BB and B tier names today carry coupons more like UST bonds. This cycle, the “regulatory arbitrage” has lost some of its impact at the speculative grade divide with much less dislocation on downgrades from BBB to BB vs. past cycles.

Default risks are lagging factors, but the heavy BB mix changes the equation: The default risk increase moving from the BB tier to the B tier is exponentially higher. The move from B tier to CCC tier is another exponential leap higher. That context often gets lost in equity market dialogue. The pejorative assigned in equity markets on a “downgrade to junk” is still overused when not all “junk” is created equal (not even close). The reality is that some BB names can be selected that have materially lower default risk than many BBB names. Investors can find BB tier issuers with less prospective volatility than some IG names that are in secular decline. Some BBB tier names carry too much long-dated bonds that do not have natural buyers in the HY universe. Those can present even more price risk in a downturn.

Historical yields start with the UST curve, and that needs a concept check: The 1990s expansion started with a materially lower UST curve than the market saw in the late 1980s. The low starting point ramps down the expected returns available for any fixed income investor. The menu is not unlimited, and many HY investors have narrow mandates. Even though the late 1990s saw materially higher UST rates by 2000 than what was seen in 1992 coming out of a Greenspan easing. The year 1992 was when the HY market was reborn (Drexel bankruptcy in 1990 and various broker bailouts put HY business line on life support), the same low-UST effect held true after the TMT downturn and the Greenspan ease-a-thon in 2001. We saw 1% fed funds all the way into 2004.

After the credit crisis, the 5Y UST operated in a very different zip code from prior cycles in terms of UST curve and all-in HY yields. Seeing 2% handle BB issuance and 4% single B issuance in recent years was a departure too far from the concept of minimum expected yield. For managers that needed to put money to work, they often had no choice. The same is the case for sub-1% and 1% handle IG bonds.

Relative yields shows that US HY YTW is on the tighter end in historical context vs UST…

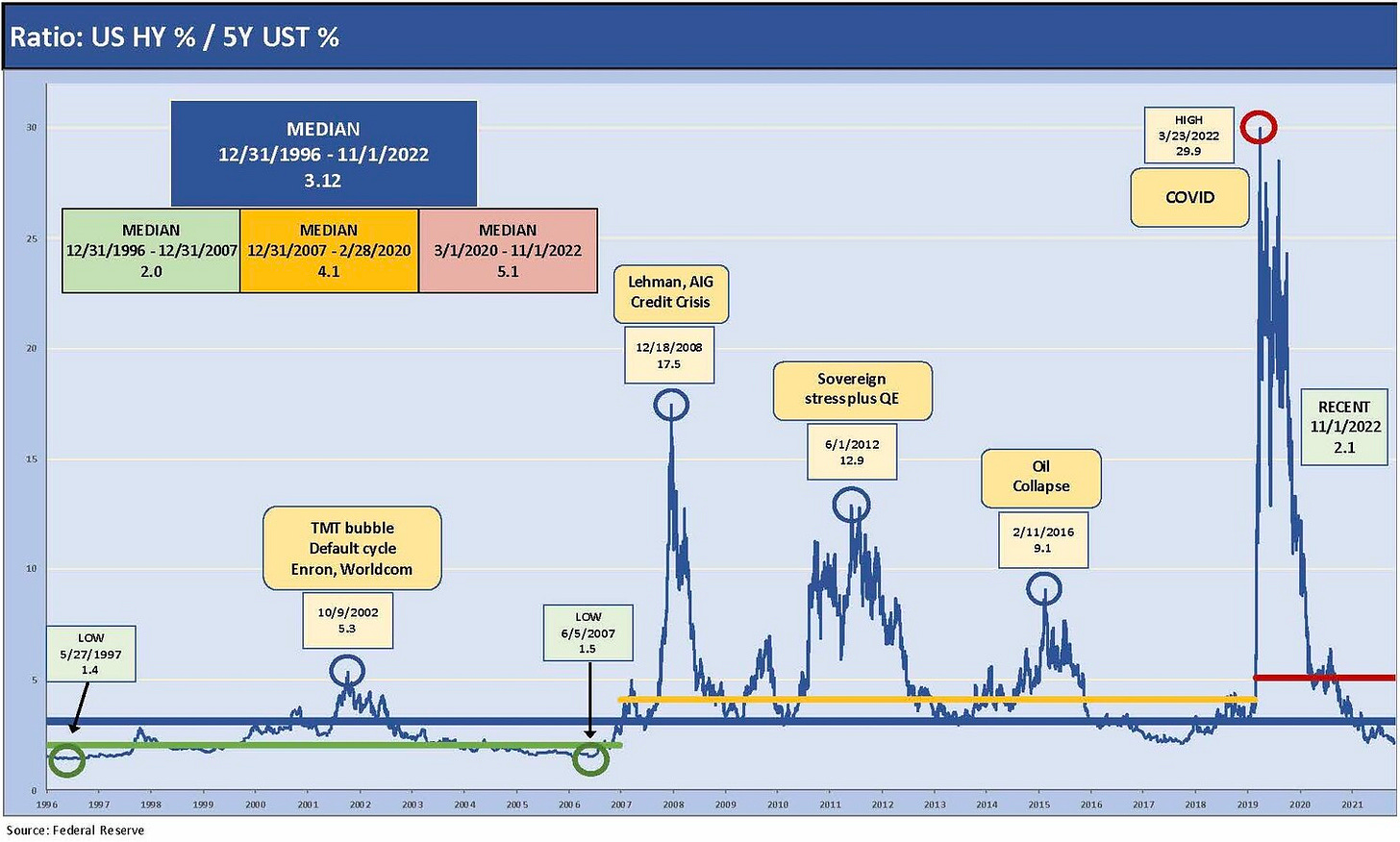

The chart below plots the ratio of the ICE US HY Index (posted on the Federal Reserve FRED site) and the 5Y UST constant maturity. The concept is simple enough. You want additional yield for additional risk vs the “risk-free asset” (although that risk-free status might get more debate in this toxic political atmosphere).

The above chart shows the ratio of HY index yields (numerator) vs. UST 5Y UST yields. One immediate takeaway is that the US HY benchmark index yields has seen a wild ride across the cycles. If you view the yield as the proxy for expected returns and compare it to the 5Y UST (a relatively good duration comp vs. US HY), then the ratio above gives some sense of scale to how the market viewed the HY risks vs. the risk-free alternative.

As with spreads, the biggest swings are found in the credit crisis and COVID as well as the 2011 period that saw sovereign stress drive UST lower and OAS wider. We also see the collapse of oil to an early 2016 HY sell-off that looks small in comparison to the more macro based stress points that pushed a low UST denominator even lower.

Key Takeaways:

Yields as a proxy for expected return: I am not looking to engage in a bond math exercise, but simply looking at a bond with a coupon, spread and duration requires that you know what risks you want to take. Then the decision is whether you are getting paid enough for all these risks. In theory, the yield factors in the coupon (cash income), the risk premium required to take that risk, and the shape and level of the UST curve. Redemption and extension risk in a volatile UST market add more risk factors but that is not the topic here.

US HY is an income vehicle, but you need to be prepared for any combination of higher credit risk flowing into spreads and UST migration or fed funds policy action that can impact price risk. This is a long way of saying ratio of yields is a conceptually sound exercise whether comparing HY to UST or HY to IG bonds.

Median yield ratios in “normal” times: “In search of normal” can be a theme by itself in US HY, but for the sake of argument let’s say the UST curve has not been normal since the credit crisis. Looking at the chart, we see a recent ratio of 2.1 for US HY/5Y UST. The long-term median is 3.1, so that relative yield comparison is not favorable and makes current levels look compressed. Since the post-crisis Fed policy support turned the relationships of credit yields to UST yields on its head, we can look at the median from before the start of ZIRP and crisis support, i.e., 2007 and before. That period offers a somewhat more normalized backdrop of classic business cycles. At least “classic” in that those cycles were not interrupted by a systemic crisis and a pandemic.

The attached yield charts reflect the Fed and UST impact that came with the crisis in the denominator. That pre-crisis median was 2.0, so that frame of reference makes the current relationship of 2.1 look more reasonable. While I no longer have access to the data, I recall a mid 1-handle to near 2 range in the 1980s using a yield to maturity basis. The index has only been around since later 1986. Those 1980s days were when new issue HY bonds were in the “teens” in yields. That means all-in expected nominal returns were in line with long-term returns on equities.

Median yields when the Fed was in crisis support mode: Looking at the timeline from 12-31-07 to 2-28-20 includes the start of the recession (per NBER), runs through the crisis period and the longest recession since the Great Depression, and ends with the longest postwar expansion. That measurement period has an end date just ahead of the two-month COVID recession. The median is 4.1 and makes the current relationship look compressed. I would argue the distortions in the UST market via Fed policy actions make that relationship less relevant to what the market is supposed to be looking at today. The Fed has moved right past normalization to inflation fighting. The one other additional median I included was 2-28-20 to 11-1-22. That period is also distorted by ZIRP and QE with the end of ZIRP only a recent event in March 2022.

A look at HY spreads…

Sometimes when looking at spreads, you can ask simple questions such as “Does the balance of risks in this HY market look like an overall median risk profile to you as we head into 2023?” In the case of the current macro and micro backdrop, I would answer “no” immediately.

The trailing numbers in US HY and low running defaults make a decent case, but the forward-looking risk factors are the problem. In addition, defaults are a lagging indicator and they have been lower in the past (e.g., 1% handle in late 2007) ahead of big trouble. The trailing fundamentals in place can be constructive and balanced, but the forward expectations can shift as other asset classes and investment alternatives feel some stress (equities, EM, other developed market credit, duration-sensitive products, etc.).

We got a taste of the limits of good training numbers in 2022 as risky assets were beaten up against a backdrop of constructive and even strong revenue and earnings trends for many issuers. As the largest sector in US HY, Energy issuers were a big help this time. In contrast, Energy was the main drag back in 2H15/1H16 as energy defaults soared.

The “What lies ahead?” X-factor has a far wider range of potential outcomes than can be captured by a median valuation. Inflation is here now, war is here now, COVID is still here (especially in the China supplier chain), and European economic stress gets worse each month on the way into a very worrisome winter with energy and inflation likely taking a heavy consumer and business toll. The China economic pressure and Russia behavior all matter since they flow into clearly definable variables from commodities and raw materials to consumer confidence to travel and leisure. The employment fallout is a focal point for the months ahead in Europe and the US.

Inflation, rapid Fed and ECB tightening, and geopolitical stress are already here. The effects could spread from the Russia-Ukraine impact on oil and gas to broader supply chain setbacks (China) if relations continue to deteriorate. The massive pressure on the EU, the largest trade partner of the US, also raises the issue around the staying power of the European alliance on Ukraine. The ability of Europe to stay united is not a given.

US Congressional budget battles also could go the wrong way, with the financial cracks starting on this side of the Atlantic. Political risk in the US (debt ceiling, legislative shutdowns, and uncertain outcomes subject to this week’s election outcome). “COVID strain roulette” (and China reactions) are another unpredictable element that are not easy to price and don’t get factored in until it has happened.

Below the macro level, another question gets to whether US HY yield in relative terms look better than the alternatives. Negligible returns on cash, low UST rates, and depressed IG yields had been helpful in the recent past. The risk-reward equation in IG corporate (duration risk) was unfavorable. With rates rising and the UST curve shifting, bond pricing still has unattractive price symmetry, but a few good inflation news items could change that and at least build confidence in stability (i.e., less duration loss exposure). In theory, equities also boasts better price symmetry than duration losses that will not be regained until inflation converges somewhat more with fed funds.

If you believe duration is stable or bullish from here, that raises questions on what gets that to happen? Weaker fundamentals? Lower oil? Recession? In some of these negative fundamental scenarios that support the UST curve, the side effects on HY credit spreads will hurt US HY. If the UST market does rally and one can make the case that we now live in a 4% world for the UST, you have a better case in IG bonds. That is a big “if” on the 4% world theory. If the recession comes, and inflation stalls, IG bonds see the duration threat eased. In contrast, US HY will feel the economic contraction in wider spreads and rising default risks on the low end of the HY spectrum.

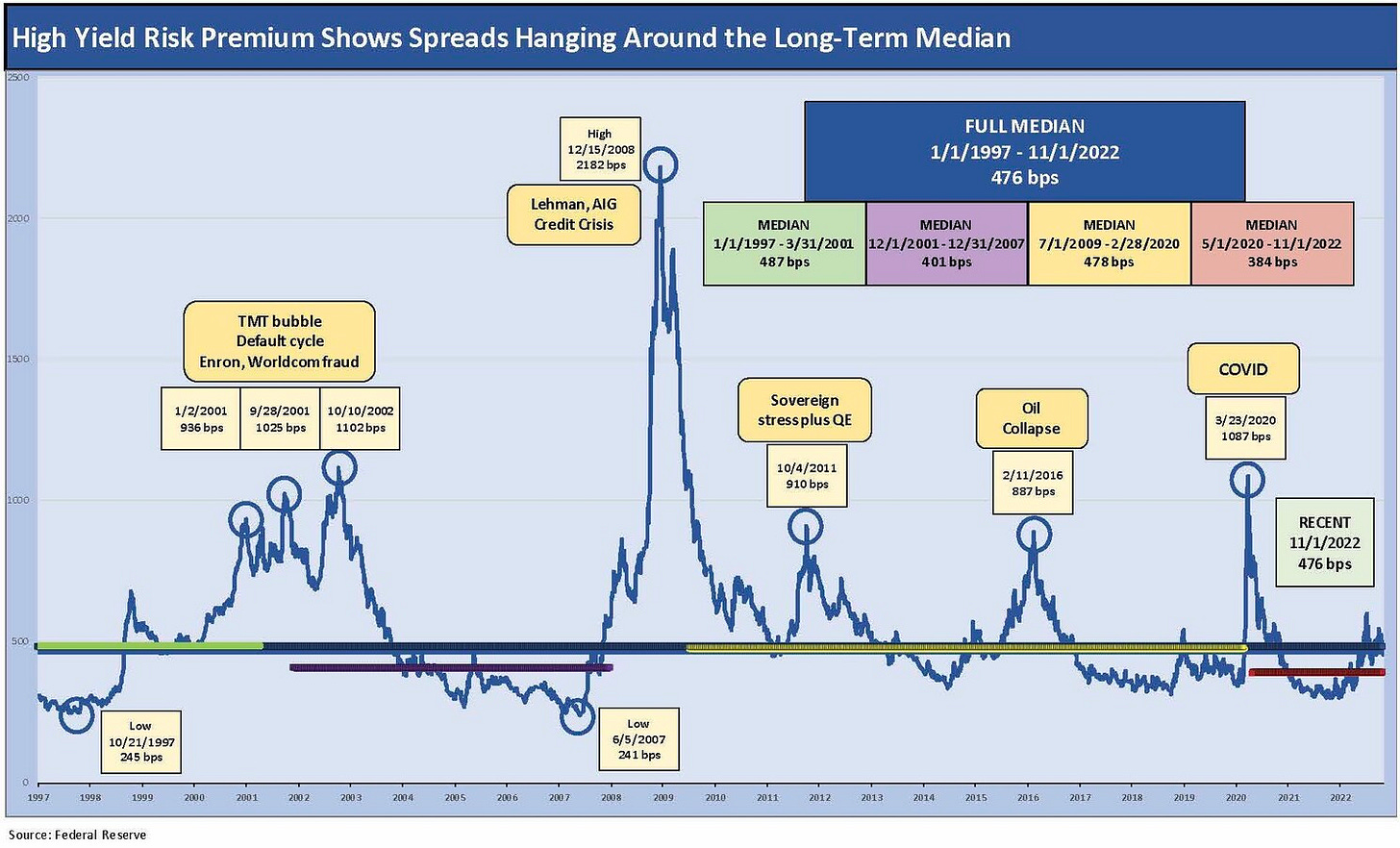

The chart above tracks the wild swings in HY index OAS across the years from the 1997 OAS lows. OAS data before 1997 is not publicly available, but both 1995 and 1996 were solid years for credit. 1994 had been a mess as covered in other commentaries. I show the swings in spreads across time and include a long-term median from 1997 through the start of Nov 2022. The full median is +476 bps. The chart provides details on the major spread waves (TMT bubble in 2000-2002, credit crisis, Eurozone sovereign stress of 2011, the oil crash of 2H15/early 2016, and then of course COVID in March 2020.

I also break out some medians during expansion periods using the NBER dates as the dates for the frame. I have written about how we differentiate credit cycle from business cycles in other commentaries, but we use NBER dates for the purpose of an objective framework.

I show the median OAS of +487 bps from the 1-1-97 start of the data set to 3-31-01 (NBER peak month). I then use 12-1-01 (start of expansion) to 12-31-07 (cyclical peak per NBER) for that cycle with a median OAS of +401 bps. I use the post-crisis expansion date of 7-1-09 to 2-28-20 (pre-COVID peak per NBER) with a median of +478 bps. The post-COVID expansion from 5-1-20 to 11-1-22 posts a +384 bps median in the currently continuing expansion of approximately 2.5 years. The 2022 HY spreads have materially widened from 2021.

As we look at the HY spreads posted today, current levels are in line with most of those earlier cyclical expansion medians. The main exception was the post-COVID 2020-2021 strength, which saw tighter spreads at the median. For 2020-2021, a major risk rally and very supportive Fed and fiscal stimulus kept risk appetites high. HY spreads moved into the 300-handle range in 2020-2021.

Key Takeaways from Spread History

The late TMT years: I start the chart near the TMT period cyclical spread lows of 1997, which was when ML (later BAML, later ICE BAML index) started delivering daily OAS data. We see the tight spreads in 1997 on the way to a late 1998 spread wave on the Russia default (Aug 1998) and ensuing LTCM margin crisis. That noisy period in 1998 (including various Lehman rumors) prompted the Fed to ease in the fall as it unofficially organized an LTCM bailout. I cover those details in our other cyclical commentaries.

The TMT bubble sent the US HY market into the longest (not the highest) default cycle in US HY history with a few 1000 bps handle peaks in 2001-2002 as noted on the chart. During 2001, Greenspan was vigorously easing on rates. That not-so-fun stretch include the Enron scandal and bankruptcy in late 2001 and the WorldCom fraud crisis in the summer of 2002. In addition to Fed easing, we saw a tight supply of UST. The US discovered the concept of a bipartisan balanced budget in 2000 (that will happen again the next time Comet Kohoutek swings by). With lower borrowing needs, UST long bonds ran lower in yield in 2000 even as HY credit quality was under pressure. Spreads widened and hedging was a challenge for IG desks.

The credit crisis OAS spike vs. COVID: A systemic crisis makes spreads somewhat irrelevant with bonds trading like stocks and often on low dollar price basis. The investor job in such markets is to gauge an expected return over a theoretical time horizon. Secondary liquidity collapsed after the credit crisis. The ability and willingness of the banks to take more risk was limited given the backdrop. In contrast, the post-COVID period was somewhat about finding weak sellers. The UST curve shifting down and a ZIRP-fueled risk appetites lowered the cost of taking positions for those with the skills and ambition to take more HY bond or leveraged loan risks. Then the big bounce back came. The big difference in 2020 vs. late 2008 was healthy banks, dramatically lower counterparty risk, and no major brokers (e.g., Lehman, Bear) leveraged to the gills and dependent on commercial paper (the major brokers were gone, merged, or had become deposit-taking banks)

The secondary liquidity and market-maker risk factor: Secondary liquidity can got quickly pummeled when one of those “six standard deviation events” slammed the market. The reality was that mutual fund redemption risk was on the minds of those who had to make markets to fund such redemptions. In other words, the street market makers. The effect usually is that bids backpedal. That backdrop is usually a phenomenal opportunity for more discretionary asset pools to step into the panic whether it be hedge funds, pension funds, or wealth managers with a high risk mandate. Those portfolios can control their own redemption destiny (with a qualifier for margin call risk in some cases) while mutual funds have to consider outflows and all those “liquidity transformation risks” the Fed likes to write about. The single best time for a pension asset allocator to move in size into HY is when chaos is the highest and secondary liquidity is the most impaired. Finding a supply of pre-screened bonds or a two-sided market might be the hard part. Moving into a market that way takes some confidence.

The oil market mini-crisis: The oil market sell-off and HY valuation stress of 2H15/1Q16 was heavily tied to the escalating upstream energy crisis and soaring default risks. E&P was shaping up as a sector that started to look like single digit unsecured recovery prospects for many. A growing number of issuers in the largest US HY sector were facing the exact same correlated variable (the price of oil and to a lesser extent the price of natural gas). The street was necessarily playing defense on making markets and the headlines out of restructuring by the early defaulters were raising alarms. These sorts of market conditions (low UST, badly impaired secondary liquidity, poor transparency on the default transmission mechanisms, etc.) are worse in the world of the Volcker Rule since the street can no longer not dive into the prop side (in theory) and tag team with hedge funds like they did in the “old days.” There is simply less capital in the game dedicated to credit by choice or by regulatory fiat.

The COVID meltdown: COVID bordered on a shutdown (brief as it was) in many segments of the economy, but credit risk management confidence was on a stronger foundation than in the credit crisis. Spreads peaked materially lower than in the late 2008 period. The 2020 coast-to-coast journey for US HY OAS was wild, but the year 2020 ended with HY OAS the way the year started – with HY index OAS under 400 bps with 300 handles and only slight wider on the year. That was an amazing swing and turnaround, and the vaccine brought a tailwind to the final leg of the rally. US HY even had a small positive excess return in 2020 on the coupon income advantage despite modestly wider OAS.

The 2008/early 2009 crisis was dominated by the structural risks that came with the unfathomable amount of counterparty risks in the derivatives-heavy world of subprime RMBS and structured credit. Such open-ended risk was not the main event in COVID. The government action was faster and the ability to see less bank systemic risk was also a mitigating factor. The UST and Fed were tag-teaming very effectively across their market liquidity support mechanisms. The UST and Fed had a good starting point from the credit crisis template.

The interesting twist was that a refi-and-extension wave quickly unfolded and refinancing risk was lower – not higher when the smoke cleared. Market structure came out less risky on the other side. The work done by Powell and Mnuchin was masterful in execution and showed a very good understanding of the credit market dynamics. Powell had a background that included a stint in private equity (he was not an econ egghead). Mnuchin knew the credit markets well as a Goldman big shot and via his investments in financial institutions.

The trick for the Fed and UST was to avoid disaster by providing liquidity backstops that would not necessarily have to be used (in theory). Adding in corporate bond repurchase flexibility was more about the concept of broad credit asset class support. The existence of the support reassured the HY market and off we all went. Refi boomed. Spreads rallied. That success did not get enough credit

The macro picture:

Dislocations are always the best periods to buy: The outlier scale of spreads in some of these charts unfold when fundamentals and secondary liquidity panics (notably in the face of HY fund redemption risk) thin out. The HY market is dependent on fewer OTC market makers now despite a record sized market in leveraged finance. The major desks have the added constraints of the Volcker Rule. The material price dislocations along the way offer a reminder of the exponential differences in default risk between the upper tiers of US HY and the lower tier.

When spreads decompress during bouts of risk aversion and secondary liquidity vacuums, the impact can be dramatic. For an example, back on 2-11-16 at the peak of the oil credit panic we saw the bottom tick for US HY in the oil crisis. On that date, the CCC tier posted a 58-dollar price, the B tier was 84, and the BB tier 93. Then the HY market put together two of the best months in US HY history (March 2016, April 2016). On 3-23-20 at the peak of the COVID crisis, the CCC tier was 59, the B tier at 78, and BB at 84. That was before Powell and Mnuchin got the ball rolling. By the end of the year, the CCC tier was 95, the B tier 104, and the BB tier 107. That was before adding in the coupons collected.

The market faces a very tenuous risk backdrop as we enter 2023: The expectations are for much weaker fixed investment (housing, nonresidential structures, possibly equipment), a softer consumer sector, rising unemployment, and some very noisy conditions out of Europe. These will make for a tough macro story set against rising rates. My near-term expectation remains for the forward rolling three months of HY spreads to be higher than the trailing three months. The real excitement will be in 2023 as higher rates work their way through the system, and asset quality deteriorates in the corporate and consumer sector (e.g., subprime autos). The top-down stories from a tough European winter and weaker China growth could start to roll into the risk pricing for credit globally.

Interest rate risk vs. fundamental credit risk: The Fed “slower, higher, longer” discussion and how to frame US HY vs. high grade bonds will be a major asset allocation decision. US HY materially outperformed IG Corporate benchmarks on the painful duration performance. A little extra coupon and lower duration helped US HY vs. UST benchmarks. In terms of global credit, there is also the “strong dollar and rising UST” theory that it will blow up EM debt. That is outside my wheelhouse but remains a back-and-forth debate. The price upside in equities looking out beyond 2023 adds another element in the multi-asset debate with price risk in fixed income dominated by duration. Inflation is not making that trade-off of duration vs. fundamental risk any less complicated.

Oil price risk: One irony in the market turmoil is that so many issuers in US HY and in the crossover credit tiers are heavily exposed to oil and gas. The cause of so much inflation – oil and gas prices – that impact the macro pressure across the US and Europe also see issuers minting free cash flow, rewarding shareholders, and improving their credit profiles. That is a very important variable in US HY performance. On a positive note, E&P sector capital budgets will improve in 2023, and that flows into the investment line of GDP. Regional economies with heavy energy exposure will get a lift with the related multiplier effects by region.

China risk: China as always is the toughest nut to crack, and the Taiwan issue and trade clashes could compound some supply chain problems. China could also whipsaw commodity prices depending on demand trends and domestic stimulus. As we saw in late 2014 to early 2016, oil, metals, steel and chemicals all turn on China demand. The noisy summer and early fall of 2015 (China stock market volatility) was a disruptive factor in risky asset pricing even as oil was ready to come crashing down late in the year into early 2016. What is not on the table now in HY pricing would be a major disruption with China that hits critical components to the US manufacturing sector. The chip battle for autos is not over yet. Away from the Taiwan issue is the range of goods that come in from China. This is also a material inflation variable from the supply side. Supply chain disruption can be by accident or by design given geopolitics.

Russia-Ukraine: The geopolitical game theory around how Russia, China, an OPEC+ might change strategies would certainly be a determining variable in the energy markets that drive US HY. Imagine if peace broke out in Ukraine and what that would mean for oil? Do we then start the redemption risk dance all over again in US HY on oil price declines? Or does the relief in Europe and the macro “tax cut” that comes with lower oil make all the difference and send rallies in risk across the markets? Most likely all risk would win big with equities at the top by far. In theory, these would be an inflation killer. Duration likely trumps spread compression under that scenario. Equity wins, IG wins, and HY wins in that order. IG wins the most from this price level since HY is not that wide (yet). Food commerce opens back up. The Fed can stand down. Powell can say “I am going to Disney World.”

Giving the risk premiums some % weights…

I plot the OAS % 5Y UST to give another vantage point on the proportionate risk premium one receives for taking incremental risk down the credit spectrum. The main factor to remember is that the numerator is the OAS (risk premium) in absolute terms and the denominator is the 5Y UST in basis points. The post-crisis UST curve was so low relative to the pre-crisis cycles that the COVID numbers run off the chart.

Sometimes yields don’t matter, and it is about dollar prices: Using this yield chart was in part for dramatic effect but also to drive home the point that US HY reaches a point where the UST curve is no longer a comp. Some layers (BB tier) might be viewed on all-in yield basis in such tumultuous times or with an eye on coupon income. In the most dislocated markets, it is simply about dollar prices and what the target end price will be over a defined time horizon. I remember one story from a hedge fund that just said “Let’s drop everything we are working on and pick 25-50 names” when the energy market was blowing up from the oil crash. As we mentioned earlier, there was a lot of upside in the crisis markets for issuer picking.

The small denominator effect: I have always warned against ignoring these ratios as just simple math and low denominator. Of course, the long division is not complicated but neither is the basic concept – that the risk-free asset in the denominator is an alternative investment. The UST starts the excess return conversation for the return generated for taking credit risk. The same goes for cash investment alternatives or IG bonds. The point is that the math is simple. The hard part is framing and pricing the risks.

The medians for OAS % 5Y UST: The median across the time horizon was 208%, so that puts the risk premium for US HY overall in relatable context. For the period from 1997 through June 2007 (we traditionally call June 2007 the end of the credit cycle) we see a 97% metric vs. 5Y UST. The post-crisis median using 7-1-09 (after the June 2009 trough) straight through to the current 2022 levels is 310%, which I would argue is distorted by COVID and Fed policy actions on UST in the denominator. The recent 108% level is like the absolute OAS comparison we saw earlier in that it is hanging around a median level from the pre-crisis years. Given the moving parts ahead, this current trading level is getting the benefit of the doubt on the absence of recession or more setbacks on the macro front. That means I see it as too tight for what might lie ahead.

A note about the picture at the top of the commentary…

The Hanson Brothers became part of the cultural fabric of the hockey world after the movie Slapshot (starring Paul Newman) back in 1977. While Slapshot just missed the long list of “thinking man’s films,” the plot has the merit of capturing the capital market’s sense of violence during times of turmoil (at least the fight scenes did). The movie captures how economic stress requires some distraction occasionally. (The plot revolves around a decaying mill town’s minor league home team). The movie was funny. The markets are more tragicomedy.

During the release year of 1977, CPI hit 7.0% in April, the highest since 1975. Unemployment had a high that year of 7.6% before life got uglier at the end of the decade. The Federal Reserve Act of 1977 became law that year and set the “dual mandate” (even if it looks more like three): “maximum employment, stable prices, and moderate long-term interest rates.”

On the topic of that Federal Reserve Act from 1977, one of the funnier moments in a Fed testimony before Congress was when an irate saber-rattling Congressman looking for his tough guy airtime said in aggressive accusatory language to Chair Ben Bernanke “What gives you the right?” The soft-spoken Bernanke informed him “You did. Congress.” More specifically this 1977 Act did. (My translation of Bernanke’s response: “You ill-read pinhead if you are going to rattle your saber, know how to use it.”).