Footnotes and Flashbacks: Week ended January 13, 2023

This week saw solid bank earnings and remind us that a hard landing takes a weak bank system or a new shock.

This Week’s Macro: Broad index returns, CPI/Inflation, Yield curve shifts, 3M-5Y UST inversion spikes, Bank earnings as both macro and micro factors, Debt ceiling brinkmanship.

This Week’s Micro: ETF rolling 3-month returns, Bank earnings, KB Homes as another homebuilder timeline proxy, Delta’s headline earnings and sell-off.

MACRO

Below we flag some trends or developments in the “macro” top-down variables. We also include some cross-asset total return charts and yield curve visuals to complement the themes.

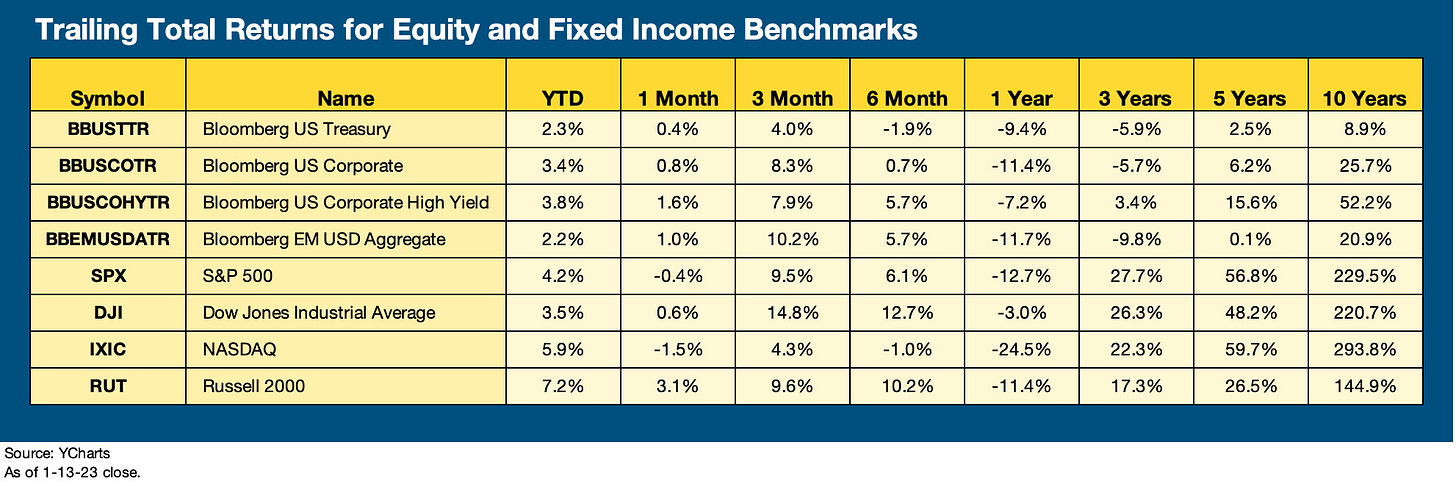

The chart below frames up the main asset classes across debt and equity with their respective running total return across trailing time horizons. The pain of 2022 in debt and equity alike is very much in evidence back to the trailing 1 year time horizon as inflation, the UST migration, and the Fed tightening cycle left nowhere to hide. Life was very difficult for fixed income asset allocation strategies in a post-ZIRP world, and the new UST curve configuration created some complex challenges in asset allocation to go with some healthy income and return opportunities as portfolios rebalance and strategies adjust.

Week ending Jan 13, 2023: This past week was dominated by the fresh debates around CPI and where the Fed forecasts and market pricing has diverged. We also kicked off earnings season with the big banks at the top of the headline list. Banks is one of those sectors that is as important from the top down as it is for portfolio issuer and industry weightings in equity and debt portfolios.

So far in 2023, the spread tightening YTD and more bondholder friendly yield curve sentiment at repriced levels is helping corporate debt benchmarks in IG and HY. This comes after a brutal set of 2022 return numbers that were hit by duration pain and widening spreads. We even saw IG bonds on the bottom of the 2022 calendar year rankings behind UST, AGG, and HY (see The 2022 Multiasset Beatdown 12-32-22).

As noted in the chart above, the rolling 1 month and YTD returns into the the new year has IG and HY bond benchmarks getting an early year pop. US IG bond spreads stayed in a very narrow range in December and into 2023 in mid-single digits. Meanwhile, US HY swung around just below a 50 bps range in December (using ICE BaML index numbers). The IG market is still holding in a narrow range in January so far, while US HY grinds tighter YTD (1-13-23). There are a lot of top-down variables to play out in credit risk, and the bulk of HY issuer earnings come in the next few weeks.

The headlines will also be zeroing in on debt ceiling drama and the not-so-small matter of a potential US default. The summer and early fall of 2011 (peak HY spreads on Oct 4, 2011) will get back into the conversation (see BB vs. CCC Spreads: Choose Wisely 1-8-23 ). That was the last time some Congressional taking heads found a UST default an acceptable solution in the name of ideology and personal branding.

THE WEEK BACK...

CPI and the inflation fight: The CPI release brought good news with the sixth straight month of declines at the headline level with CPI well off the June 2021 high and the Core CPI level down from the Sept highs (see CPI Wrap for 2022: The Beginning of the End? 1-12-23). In our comments on CPI this week, we ran through the various focal points we see around inflation, including “CPI ex” metrics (ex-shelter, ex-energy, ex-food, Service ex-shelter, etc.). The drilldowns into various Services lines of late are tied to the challenges arising from the question of tight labor and what that means for the stickiness of a wide range of inflation metrics.

In an economy that is essentially a service economy with a lot of bodies manning the battle stations, the supply-demand for labor is a tough needle for the Fed to move unless they opt for the “serious damage” game plan that comes by turning up the heat on demand destruction. The less bearish scenario is “higher for longer” and taking the risk of only a modest but helpful decline of headline CPI and PCE. That buys investors some time to take stock of events in Washington and in geopolitics, while also gauging how bad the European fundamentals might be as winter drags on.

CPI still trumps PCE in the headlines and the Fed actions ahead are likely to be muted. The swing from goods to services is keeping the labor focus high as unemployment is back to a 50-year low this month and jobs openings remain at very lofty levels (see December Jobs Report: Mixed Feelings 1-6-23). For shelter and the important multiplier effects of the housing sector, the lags in timing on rental rates in the BLS data vs. what we see on the screen is a major reason for an ex-Shelter view on CPI and Services. The ex-shelter review still shows plenty of higher numbers in sticky inflation categories. Those services pressures arm the Fed in the higher-for-longer back and forth.

Bank earnings are both a macro and a micro factor and—for now—push back on hard landing scenarios: The health of the bank system is something that no one takes for granted after the credit crisis experience even if the banks pushed through COVID without a missing a beat. The major banks even saw a wave of new trading revenue and investment banking opportunities, a refinancing tsunami in corporate bonds (refi and extension volumes) and household debt (mortgage refi). There were plenty of growth stock IPO business in 2020-2021. That party is over now.

The 4Q22 numbers for the first four major banks generally surprised to the upside as we discuss in the MICRO section further below. WFC was an exception but had a lot of noise in the numbers from preleased issues. In looking for signs of where asset concentrations or counterparty risk are more than cyclical and/or constitute a major threat to bank health – and thus might leads to severe credit contraction – we don’t see it. Provisions will go up and charge-offs will go up, but that is more a case of business as usual.

From a macro standpoint, the hard landing forecasters need a weak bank system to make their case stick. We had that in 1990-1991 and in 2008 (to the extreme). We would argue that the 2001 recession and 2000-2002 default wave were more about bad deal flow that did not maim the banks in the usual fashion. The 2001 experience was a very muted real economy downturn but one that brought a few years of legislative and regulatory bashing. Unfortunately, the result was very low fed funds despite the relative health of the banks.

During 2001, Greenspan supported an extended easing well into the next recession, which set the stage for bad behavior in mortgages and structure credit (see Greenspan’s Last Hurrah: His Wild Finish Before the Crisis 10-30-22). There was also no shortage of counterparty excess that created much bigger problems later. The major banks held in very well across the “TMT cycle” with maybe one or two brokers facing some outsized risk (Bear and Lehman, who are no longer on the playing field).

We did not have a weak bank system during the 2000-2001 market turmoil even if we had tangible evidence of a lot of bad actors on the client side (WorldCom, Enron, etc.). That period followed a stretch of the street showing an uncanny ability to print bad deals – and a flow-based and competitive impulse from investors to buy them. The LTCM counterparty crisis and EM contagion in the late 1990s was not enough to drive a hard landing any more than the longest default cycle in history. The year 2001 was thus a softening for the economy but only a very hard landing for the credit default cycle. Of course, a few executives had some hard landings on some prison cots. Credit contraction was an issue for bad borrowers but not for the broader bank system.

The 2008 swoon in the banks was other worldly after a 2007 credit peak left the financial system with a lit fuse and a lot to blow up (see Wild Transition Year: The Chaos of 2007 11-1-22). We do not have to highlight why an unprecedented series of major bank and broker failures and government bailouts was more than a real economy dagger. It was a sword in the heart of the economy – a credit contraction of the worst sort. The credit contraction only avoided a total meltdown of credit availability via the support of comprehensive fiscal and monetary activism. That credit contraction and asset quality plunge drove a hard landing that was also the longest recession since the Great Depression.

In broad strokes, the bank system story in 2023 pushes back on hard landing outcomes. Damaging contraction is not in the cards even if standards can tighten as appropriate for the risks across various borrowers and asset subsectors. Congress might upend this and China-US tension turning hotter could as well, but those are not our base cases. We can see chaos, fear, and ignorance unfolding in Washington but not a trip to systemic Jonestown.

For now, the nuances of credit contraction risk are in the “micro story” of banks and their strategies. It is not a macro headwind of the sort that has been part of the catalysts to past hard landings. We have had a few hard landings since 1980 that came on the back of structural upheavals in economies (broad or regional) or when shocks rattled the financial system (the oil patch regional meltdown and spill into Texas Banks, LDC exposure and emerging markets in the pre-Brady years, commercial real estate in the early 1990s, housing in the mid-2000s, and the credit bubble and counterparty excess of 2006-2008 rooted in bank system interconnectedness). Today, the argument is more about loan quality and the health of reserves across various corporate lending and consumer business lines. That is in the micro piece for your friendly neighborhood bank analyst.

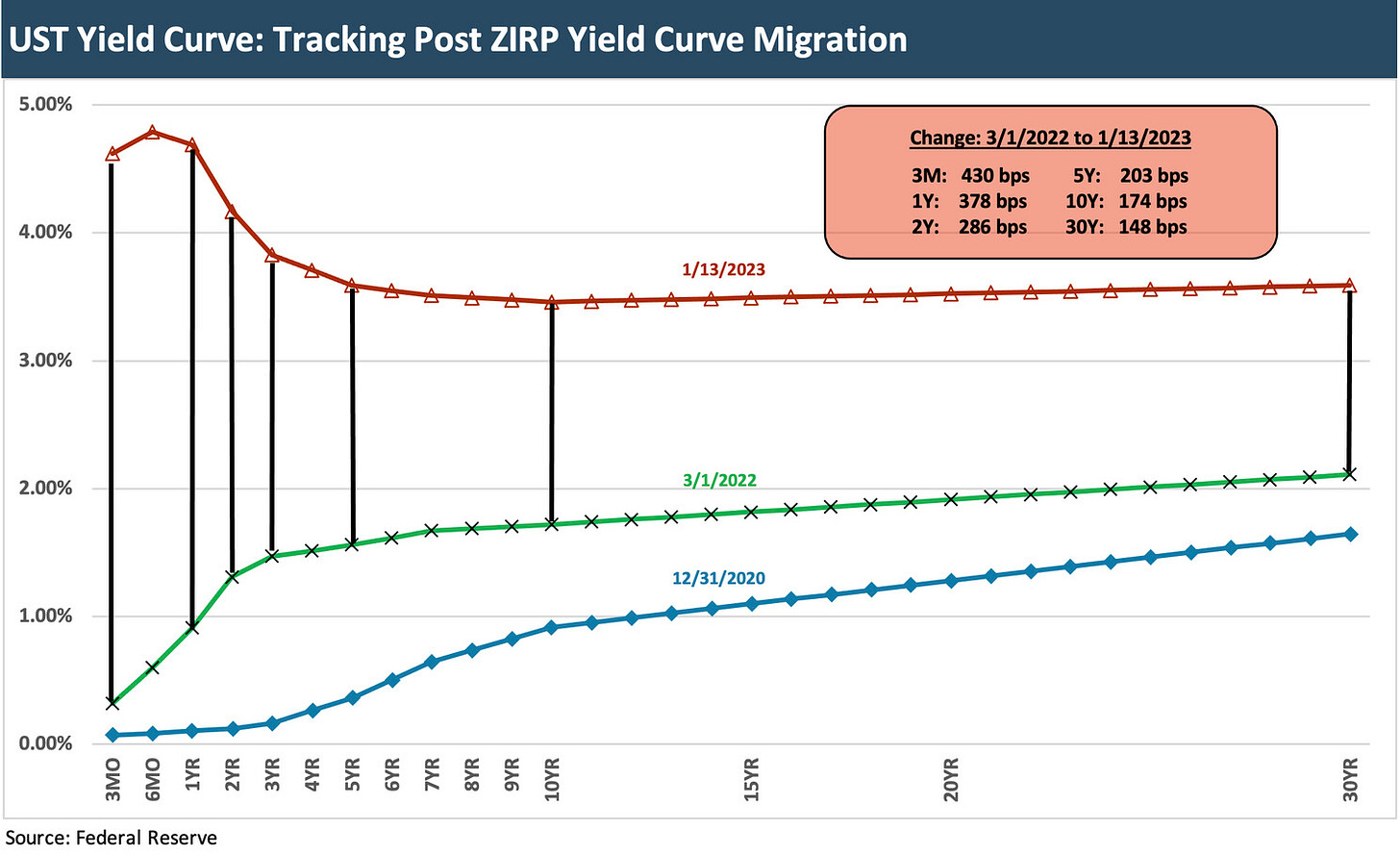

Yield curve inversion and divergence of the Fed vs. market view: The yield curve debates naturally wrap around recession handicapping and inflation and the timing and magnitude of future Fed actions. In that regard, the past week was a busy one. With earnings kicking off with the major banks and the latest CPI numbers, the market has a lot of input rolling out that the market can lean on to vote again on recession risk and soft landing vs. hard landing. Below we plot yield curve charts that include the upward shift and inversion of the UST curve. We also flag the inversion vs. prior downturns in another chart further below.

The chart above frames three yield curves that can tell a running story on how far the UST market has shifted since the post-COVID ZIRP timeline and the belated moves by the Fed to start tightening in March 2022. We plot the 12-31-20 UST curve to start the chart before the 2021 rebound kicked into high gear. The 2021 GDP numbers posted the first 5% handle annual GDP growth rate since the Reagan years. The early November 2020 vaccine news had set off a major rally and then the capital markets boom was on as well. Over the past two years, the supply chain challenges did not blend well with soaring demand. We saw rising inflation running alongside fiscal stimulus and sustained ZIRP. The late start to tighten brought us the 2022 total return damage.

We highlight the differentials (in bps) of the 3M, 1Y, 2Y, 3Y, 5Y, 10Y and 30Y UST from the beginning of March 2022 vs. the most recent yield curve to end the week (late Friday pricing). We detail those numbers in the box. We would have to dub that The Mother of All Inversion Shifts. The front-end rates are making it easier for those who want to be defensive to park in cash/equivalents at levels more like REIT equity yields from earlier in the year when the market was still in a ZIRP world. The 4% handle type of yield on cash in money market fund and 3% for numerous money market products is going to pressure more banks to step up to the plate. That of course will squeeze the bullish net interest margins posted with the start of bank earnings season.

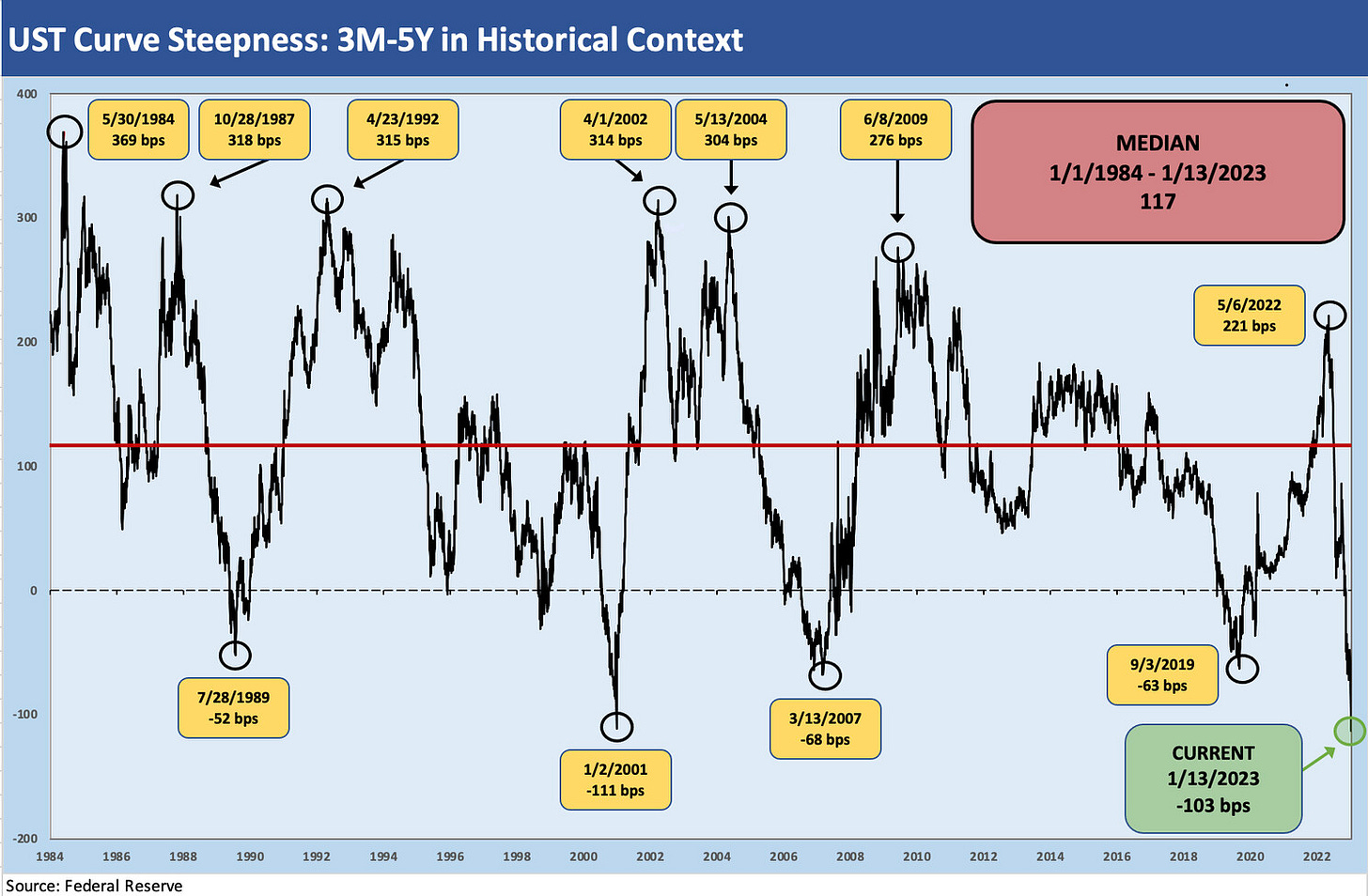

The chart above updates the 3M to 5Y UST inversion. This segment of the curve is more interesting to us right now given the fresh game clock on cash as an asset allocation alternative. The short end of the curve also drives loan fund demand and is a good indicator of the reach for yield impulse for US HY bonds. The impulse should not be a strong unless one is bullish on spreads and the cycle. There are a lot of lower-coupon HY bonds in the market after the refi and extension wave after COVID. That is the income X-factor after such a rise in the curve. We see HY spreads as moving comfortably wider into 2023. The 3M-5Y ended the week at -103 bps. As the chart shows, we need to go back to early 2001 to see that type of inversion. Things did not go so well in financial assets after that date, but the real economy was resilient. But that was a very different market. The big difference this time is the high inflation not seen since the Volcker years.

We already have discussed the recession predictor debates around the curve (see UST Slope Update: Some New Inversion Highs 12-8-22, UST Curve: Slope Matters 10-25-22). From our vantage point, that “inversion as recession signal” debate is still rooted in the causes and not the symptoms (i.e., the curve). We can find an ample supply of causes with the inversion blinker on. We also do not see those as adding up to a hard landing.

The income and return aspects of cash are an easier discussion now, since the 3M to 5Y or 3M to 10Y inversion offers generous income in a 2021 context. The Fed now gives the saver/retirement investor time to sort out the moving parts with some critical Fed events ahead (plus a side order of Congressional insanity). Even JPM indicated in its earnings guidance that it might be forced to be a bit less miserly on its deposits and cannot depend on customer complacency to keep funding costs down.

That cash question will linger, but the pain of foregone coupons and opportunity cost during the wait has been eased as the Fed kept hiking (see The Cash Question: 3M-5Y Yield and Slope 10-19-22). The challenge in a flat to inverted yield curve is that the reach for yield impulse mellows out and appetite for extension needs the incentive of a steeper spread curve. The appetite for duration in higher quality might mitigate that for some investors with a yield curve view that exhibits relative stability and even a chance for duration gains across the year.

A slight downshift in the UST curve a sign of more ahead?: For the past week, the CPI index kept the “Fed view vs. the market view” debate alive around what the FOMC sees ahead vs. what the market is saying. The yield curve from 2Y out to 30Y moved slightly lower over the week in positive news for those with continued constructive views on duration returns ahead. The more bullish views on high grade corporate bond returns see a combination of moderation on the inflation line items and more favorable “YoY math” in the CPI comps keeping headlines on inflation trends favorable.

The investor flows into IG and upper quality HY (BB tiers and fallen angels) might stay upbeat on the newly repriced IG index yields we see today. The “hedge your bets” angle is that if recession does come and is not a soft-landing, there is a better risk-reward in being up in HY quality and in better positioned IG names. Those concentrating on BBB will need to keep an eye on selecting less ratings-vulnerable BBB tier names with a heavy long-dated mix of bonds on the yield curve. Those get very sloppy on downgrades.

The idea for IG bulls is to win on yield and relative spread stability plus a bit of extra duration returns. If spreads get hit on bad macro news, then the negative excess returns will have a better offset in UST curve return benefits. At least that’s one school of thought. We have been in that camp since there are so many crazy outcomes one can cook up (see Risk Trends: The Neurotic’s Checklist 12-11-22). This is not a median US HY market risk profile but that is where the spreads hang around (see Old Time Risk: HY Season Faces Challenge 11-7-22).

The Debt Ceiling arriving soon: The noisy week of the McCarthy speaker drama was more like a hush-toned prelim dialogue compared to what lies ahead. The new wave of extreme budget activists (or self-promoting politicians thinking power enhancement and fund raising) are waiving the default flag after Yellen started offering a timeline on when the debt ceiling clock sounds the buzzer. She indicated that the $31.4 trillion statutory debt limit gets hit on Jan 19 this week.

In a sign of the times, the most aggressive players have an opportunity to hold the government hostage. The folks driving the bus on the new 1994 GOP revolution (you really start to miss Newt) have to be taken very seriously even if you believe you have watered more intelligent plants (even plants know to tilt toward the sun). As we saw in the speaker battle, it only takes a few (arguably only one these days given the new Speaker rules) to derail the power of the purse that resides with the House under the constitution.

Handicapping the House meltdown in turn becoming a shutdown and then a default has way too many unprecedented events in it to handicap. Subjectivity rules and logic is not on the menu. Shutdowns are old hat, so the real test will be what the concessions might be to avoid the clock running down on UST debt service. An attack on Ukraine support by the extremists might be on the list, but the GOP still has a strong contingent not quite as fond of Russia and Putin. Handicapping the crossovers (GOP House members in districts carried by Biden) are a variable that might help, but institutional courage is not in abundance. Breaking ranks for either party usually requires a backbone, which would be a fact not yet in evidence in the House.

Predicting outcomes and scenarios gets to be a Mug’s game when it comes to the more extreme elements in Washington. The quest for power derives from leverage whether that is tied to votes or money. The votes are more valuable near term. The “money” comes later after the candidates build their personal brands as reliable extremists. Then the rewards come. This might seem cynical, but to me it appears empirical. Shutdowns usually backfire (Gingrich and Trump can attest to that). A UST default would certainly set off too many scenarios to speculate on now. Those scenarios including the executive branch simply paying and refinancing the UST debt and keeping the government otherwise shut down. That has been raised in past debate on the Constitutional aspects of default (as in “default violates the constitution”). Those topics can be framed on another day.

MICRO

Below we note some news flow or trends that captured our attention during the week at the “micro” industry and company level.

Above we post some rolling 3-month returns from a range of industry and subsector groupings using a list of ETFs alongside the major equity benchmarks. We use 3-month time horizon to keep it short term but also to smooth out the volatility of weekly time horizons. We use the same mix of ETFs and subsectors as we used in our annual return comparison that highlighted the brutality of 2022 (see The 2022 Multiasset Beatdown 12-31-22). The January rally we see here is an impressive one. We see unform strength rolling 3 months across Materials, Industrials, Real Estate, and Financials. That is not a bad visual and solid run over short term.

Equity rally over the short term is not the main event: While the rally sure helps if you own the stocks that rallied, there are a lot of moving parts to frame dead ahead. The roll-up of the earnings guidance and relative performance of revenues and earnings vs. expectations will dominate the cyclical discussion points for the next few weeks. As detailed in our Macro and Micro comments on banks, the major banks gave us a good start, but there are many more concentrated issuers ahead to give us more color. We need to gauge the direction of asset quality and related valuations in some smaller financials with a narrower focus (mortgages, auto finance, consumer credit, REITs and lease rates etc.).

Among critical numbers apart from the revenue and earnings guidance will be any additional directional commentary on capex (including where that capex will be weighted geographically). In the new world of global tension and China-heavy geopolitical and trade stress, the year 2023 will see some pivotal policy risks. Semis/Chips get the headlines, but it runs across the whole value chain of product categories. Watching trade policy will be an important activity this year for researching risks.

The supply chain has shown itself to be fragile, and the chain can be broken in more than a few parts. With supplier chains shifting and nearshoring and reshoring on the hot topic list, the GDP lines in Fixed Investment will be influenced by these decisions. This in turn flows into the “no recession vs. soft landing vs. hard landing” handicapping exercise (see How do you like your landing? Hard or Soft? Part 1 12-23-22, Part 2, and Part 3.). Part 1 looked at current GDP growth lines while Part 2 looked back across cyclical periods bracketing recessions from the 1970s through current time. Part 3 looked more narrowly at the “capex” lines of the GDP accounts across time. There are a lot of constructive moving parts that push back on hard landing scenarios.

Bank earnings good enough to frustrate bears: The big bank earnings numbers kicked off the flow of updated bank information for the market to absorb. JPM, C, BAC, and WFC all saw their stocks rise well ahead of the market and well ahead of the XLF (financials ETF). As I read through releases, it is hard to see signals of hard landing risk rising. After all, credit contraction, major loss provisioning actions, and the risk of weaker margins are usually part of recession risk and more downside exposure for the cycle.

We mostly look to the major bank summaries for signs of major provisioning shifts, and the market appeared relieved after Friday’s disclosure by four of the Big 6 (Goldman and Morgan Stanley report Tuesday). JPM and BAC are the big swingers in total market cap and various other metrics. Provisions are naturally higher, but more provisioning and charge-off increases come at a lag in the cycles. The banks are crucial to comfort zones, but they are also lagging indicators after the trouble sets in.

In past lives, I was never a money center or regional bank analyst, but I looked at a lot of thrifts, consumer finance, auto fincos, and leasing operators. There is always asset class exposure and signs of trouble to look for that start with borrowers or lessees showing material weakness. I routinely held out the tin cup with many others for Lehman Brothers (and the predecessor laundry list of names, e.g. Shearson Lehman Hutton, etc.,) for commercial paper lines, so I was also sensitive to what refinancing risk meant for those on the prime commercial paper cusp. We now operate in a very different world dominated by major bank holding companies and not CP-dependent brokers that can’t take funding shocks. Deposits are going to cost more, but they are not a “hot money” area in these cases. Some will migrate for higher yields from the cheapskates of the majors.

My simple version of this first wave of big bank releases is that the numbers were solid and no red flags are getting waved. I would also highlight that the biggest problem of the past often started in major areas that lacked transparency such as counterparty risks, concentration of collateral or sector exposure (e.g., sovereigns), and industry/borrower concentration risk that you could not always glean from the earnings releases. The broker-dealer domino days are over, but the not-quite-enough disclosure problem will always be an issue.

Continued loan growth may be dull and will be lower for 2023 than 2022, but the preliminary read is at least there will be growth in some categories. Consumer asset quality will “normalize,” which is the nice way banks phrase the words “decline” or “deteriorate on cyclical pressures.” It is also an admission they likely won’t be able to release reserves to pump up earnings as some did in the post-COVID period. The very solid net interest income growth of 2022 will get squeezed as banks like JPM might find more customers migrating elsewhere for more competitive deposit rates. Funding costs will rise.

The rough stretch in investment banking, underwriting, and M&A could get better with the UST curve stabilizing and inflation peaking and now declining. Value seeking in M&A seems inevitable as winners and losers on this inflation wave shake out. We could also see some of the fallen growth stocks being targets. Some have good asset potential but cannot grow on their own due to debt or because strategic optimism has faded (e.g., digital auto retail players like Carvana).

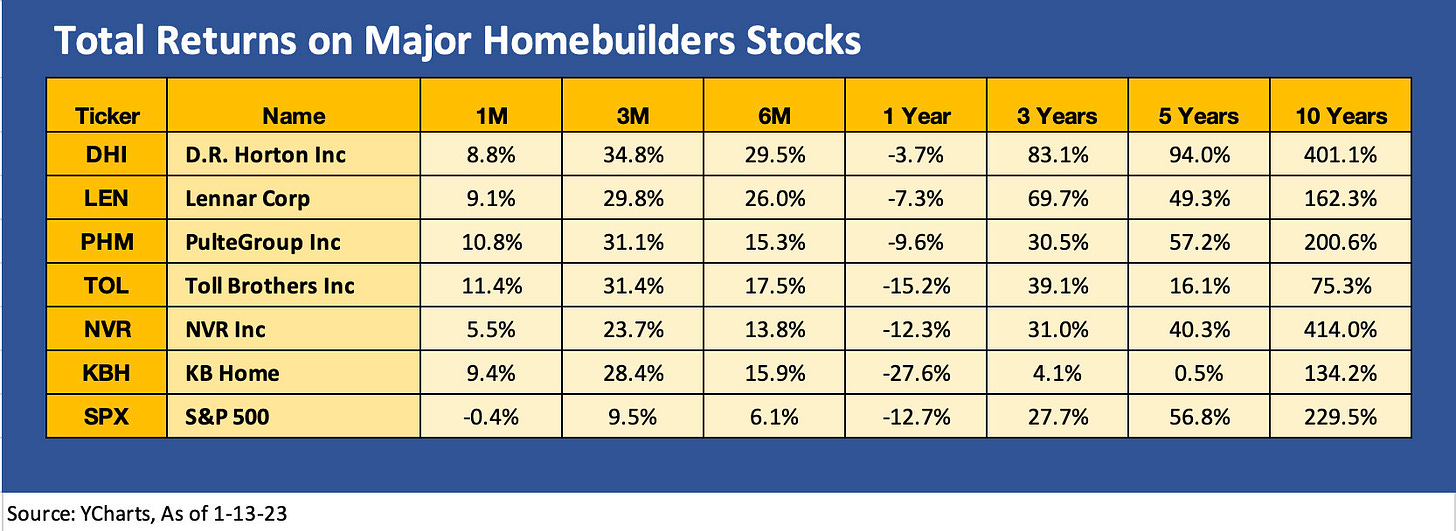

Housing and homebuilding: We get a fresh batch of housing macro metrics this week, but a builder reporting always adds some sea level color. KB Homes posted results this past week that highlight the exposure of the builders to materially declining orders with net orders down 80% and gross orders down 47%. The KBH commentary offered some insights into the need for creative strategies around how to manage the price declines in existing communities without driving even more cancellations and lost backlog.

Protecting the revenue line by getting existing contracts to the finish line and funded have a balancing act with moving remaining unsold properties. The transition to an all-new pricing backdrop needs to be managed carefully to avoid bringing the hammer down on the quarters ahead and the backlog in place.

KBH is a November 30 fiscal year, so from here it is going to be a steady phase-in of color commentary on navigation strategies and managing around order declines, cancellations and the mix of incentive game plans in a sliding market. The discussion points from the December 31 fiscal earnings reporters will be heard in coming weeks. Lennar was another Nov 30 fiscal report that already came out in mid-December, but KB has a “bit more hair on it” than Lennar and is much smaller than LEN, who is neck and neck with DR Horton as an industry leader. DHI reports on Jan 24.

KBH posted solid trailing numbers though the November quarter. Under its build-to-order model, KBH – like Lennar— had to immediately qualify the old numbers as reflecting a very different world. Now the harder part starts. The leading indicators are all over the screen each month in the headlines around sliding home starts, plunging existing home sales, and recurring discussions of how badly mortgage rates are hammering affordability.

On cancellations, KBH cited a measure of 14% of 4Q22 end backlog and framed that number as below the long-term average. As of quarter end, KBH cited 80% of its homes in production as sold. That is in line with its historical target of 80-20. Even though KBH focused on build to order, they have traditionally also offered a mix of move-in ready homes.

Net orders are down again by 72% through the first 5 weeks of fiscal 1Q23 but KBH is targeting net orders to be down by 50% for the quarter. As these builders cite these late 2022 numbers, it is important to note that the comps were vs. the smoking hot 2021 backdrop with low mortgage rates, a rush to buy houses, and a booming headline economy.

The forward-looking view from the stock market is worth watching, and the pattern of homebuilder equity performance in 2022 and into 2023 tells a story. We highlight some major homebuilder equity returns in the above chart, and the idea that the builders materially outperformed the broader market in rolling 3 months and 6 months might surprise some after the slaughter of early 2022 on mortgage rate panics.

There is no question that the legacy leading homebuilders have a lot of experience in difficult markets. What makes the current backdrop so challenging is the sheer pace of the affordability erosion as mortgages spiked. The ability to navigate wind-downs of communities, managing the contractual backlog and all while planning new communities will be a challenge. There is still a shortage of homes vs. supply, and that helps fortify nerves in these major names. The trick of course is the price mix, the geographic plan and the pace of new community investments when the credit conditions are so unfavorable on mortgage rates for the homebuyer.

Homebuilders know how to frame costs and margin forecasts based on the costs of the land and construction. The problem is gauging what affordability will look like into the next peak selling and building season. If you believe inflation can get down to 4% or less by year end, you need to plan build rates and market segment mix. Mortgage rates are a shock, but 6% handles are hardly new and have seen robust demand in the past. That is a matter of price and how that flows into the monthly payments.

Airlines: The Delta earnings report and analysts call failed to impress the market (DAL sold off -3.5%) despite very strong numbers. The problem was the forward guidance and quantification of most (not all) of the pilot contract costs. Revenue and EBITDAR forecasts remain bullish, and the credit trends for Delta especially remain solid. The expectation for full investment grade ratings was downplayed by management on some cable interviews as a 2024 timeframe. There are more than a few highly sensitive variables in this volatile sector that could make that an earlier event.

The expectation of debt reduction and higher earnings is not a bad combination regardless. Airlines have been on the short list of easy examples to push back on the idea of a sharp erosion in the PCE accounts of GDP. The fares people are willing to pay may be a function of pandemic blues, but it does not show low consumer confidence. We don’t set our sundial by consumer confidence metrics, but Friday (1-13) did post a solid one.

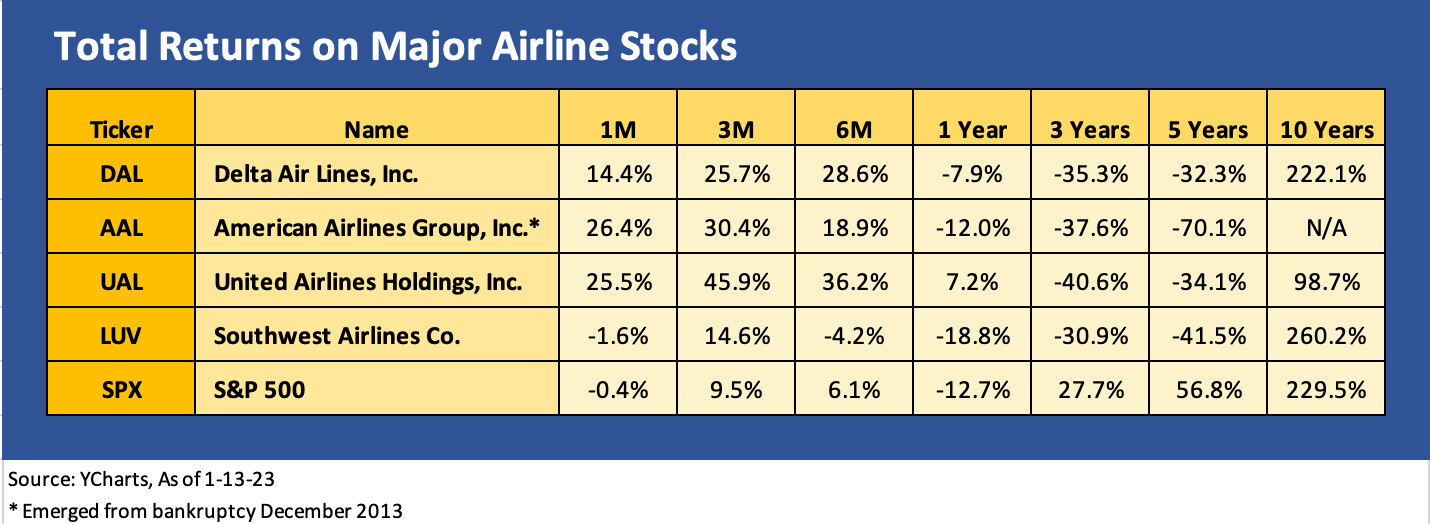

The chart above frames the total returns for select major airline equities over various trailing time horizons. We post the “Big Three” in revenues and capacity followed by Southwest with its very distinct operating model. LUV generates less than half the revenue run rate of DAL, AAL, and UAL. That said, LUV has a disproportionately large market cap relative to the revenue comparison.

The trailing total returns highlight how well airlines held in during a rough market stretch and especially in the peak travel quarters. We see the effects of COVID over the trailing 3-year period. We also see some of the effects of operational turmoil and notably with Southwest, where the low cost model has boomeranged a bit in recent weeks.

The 2022 and recent outperformance make a statement for an industry that needed Federal aid back during COVID. The airlines have been big winners in the post-COVID period on the demand side, and demand has helped the airlines push through the shattering effects of a spike in fuel in 2022 and the wage demands in the ranks – notably the pilots.

Airlines have been “feast or famine” across cycles with a long list of financial stress stories across the decades. The longer time horizons underscore the sector’s jaded and volatile history. Those of us who followed the sector in prior lives remember the bankruptcies, mergers, the mad scrambles to buy assets and grab slots/gates from the broken (e.g., Pan Am, TWA) or bankrupt (note: most of the mainline carriers at one point or another with Southwest being a rare healthy credit story across the cycles). The rise of regional jets, less hub-and-spoke domination, more point-to-point service, and the steady rise of low-cost carriers (LCCs) and “ultra” LCCs (“ULCC” was a nice ticker for Frontier) will always keep this sector interesting.

The tight labor story is going to be heard across more than the airlines, but the major carriers are facing overwhelming demand that has stretched the system to the limit. Pilots are in short supply and their pricing power is clearly quite strong. The roaring travel markets has given employees ample pricing power to make demands from pilots to machinists to flight attendants. That has been true at mainline carriers and regionals alike. Despite cost pressures, a solid name like Delta will be in a position to roll into sustained balance sheet improvement on rising earnings.

The CEO was on the cable circuit to end the week after earnings giving interviews, and he was pitching the march to investment grade. For credit quality, management framed 2024 as a year where investment grade metrics were achievable for Delta, which is remarkable given the crisis as COVID was first unfolding. The consumer and business travel outlook stories are part of framing where the consumer sector is headed in 2023-2024. That is for another day.

Airlines costs and airfare inflation is a topic unto itself. The critical variable of jet fuel prices has been volatile in recent years for obvious reasons while the spike in travel has left many carriers struggling to keep up from a manpower standpoint. The breakdown between non-fuel CASM (cost per available seat mile) and fuel costs will remain a challenge to handicap since both see very different dynamics. Jet fuel costs used to be easier to map from swings in oil, but the distorting constraints of refined product supply-demand by product category and the severe disruptions in Europe do not make generalizations very reliable. That is especially the case after such a wild year in upstream and downstream markets.

Airfare will run higher with fuel costs, but the company will not get to keep all the benefits if oil is running in the other direction. When economists write about consumer demand and elasticity, they will have a very hard time framing the ability of the carriers to do this well during such inflationary spirals for fares.