Hard or Soft Landing? Part 3: The “Capex” Lines

We wrap up our cyclical lookback at the key components of GDP in the consumer and private sector buckets.

In this commentary, we wrap up our cyclical lookback at the key components of GDP in the consumer and private sector buckets. We wrap the “Soft Landing, Hard Landing” history recap we started in Parts 1 and 2 (see How Do You Like Your Landing? Hard or Soft? Part 1 and Part 2)

We found the exercise useful in part just to demystify how bad it can get (spoiler alert: some past downturns are pretty bad). On a strangely optimistic note, it takes a lot of bad outcomes, financial system stress, and industry shocks to drive a hard landing. In the current market, we believe the odds favor a soft landing though some of the longer tailed risks lurk, which lead to significant divergence in views around the range of possible outcomes (see Risk Trends: The Neurotic’s Checklist).

China and Russia are the geopolitical wildcards that can have you buying stocks on weakness or, depending on how you handicap it, send you to buy canned goods, potassium iodide, and maybe some extra ammo. Bears can create some rather dramatic scenarios with the China-Taiwan odds making. Embargos and blockades would be a more realistic scenario than rockets’ red glare.

Trade pressures and recession risk are the more likely side effects in China-US trade if relations worsen, and then it boils down to a combination of framing energy sector pricing risks, reverberating supplier chain fallout, and inflation pressures on goods (autos again, tech, etc.). That hits a lot of major equity and debt sectors. Supplier chain stress is a more understandable fear for many consumers now, and a major upheaval in the China supply chain would drive a plunge in confidence, in turn hitting PCE.

Recent history has shown the uncanny ability of the irrational to prevail, but we assume China stays with the (very rational) long game they’ve always pursued. After all, it has worked. A full blown trade war would be irrational, but if there were a major escalation in trade actions against China, we would expect China to retaliate by restricting exports to exact maximum impact and pain.

While “soft landing” does not have an objective definition, the 2001 economic downturn posted two light -1% handle GDP quarters but also saw positive PCE across the board. We looked at past cycles and related growth rates in Part 2. In this note, we look narrowly and in more detail at annual trends in Fixed Investment (e.g., Structures, Equipment, Intellectual Property Products, Residential).

After looking back across time, we can frame some questions for 2023:

What GDP lines in the Fixed Investment mix are most vulnerable in 2023? Residential is an obvious one for more downside in the home construction cycle. Does the decline in Multifamily permits offer a sign that the problem is spreading?

Structures has six straight quarters of negative growth, and the commercial real estate risks are rising. So where in Structures (notably commercial real estate) could we see a higher double-digit slide into 2023? REITs reflect a lot of subcategories, so that earnings season will be very informative.

Equipment has held in very well in relative terms, so will some countercyclical trends help stem a worsening of the sort seen in prior cycles? Will factors such as the favorable outlook for fixing supplier chain and reshoring help counter some cyclical pressures

Will the potential for weaker demand on the consumer side and easier YoY comps ease headline inflation metrics and help push the intermediate and long end of the UST curve lower? Will this in turn relieve some pain in commercial real estate valuations and mitigate threats of broader credit contraction?

Can the US economy have a hard landing without negative PCE? How negative can PCE get with such low unemployment and so many households still sitting on near record low mortgages rates and seeing dramatically higher home equity levels (even if that home equity tally is sliding for now)?

Is there an industry or asset class shock that could materially punish the fundamentals of select segments of Structures such as commercial real estate (Office Properties are in the bearish headlines)? Will tapping the breaks on sustained expansion in some areas (e.g., Industrial. Warehouses) slow growth but still avoid more material downside?

Is the relatively healthier profile of the auto sector vs. 2008-2009, 2001-2002, and 1990-1992 and the high rate of required investment for changes in propulsion tech (the rise of EVs and battery needs) be enough to keep that industry ecosystem cruising along in fixed investment?

Will the changing landscape of global energy planning (Russia bad guys, Saudis unreliable, China very energy needy) make for a countercyclical spending pattern in upstream, midstream, and downstream across 2024? Or will the progressive wing treating “anything pipeline” like a deadly virus still rule the regulatory sway?

There are many more questions one can stack up around forward strategic investment planning and capex budgeting in the private sector. The question of “Where geographically will you spend that budget” looms larger this cycle. That is where the guidance and investor meetings will hopefully be shedding some light on the decision process and especially in the major category of supplier chain planning. For now, a lot of the theories are 10,000 feet ideas (or 30,000?) and think tank talk. The major manufacturers are not looking to alienate China and need the supplier chains functional and efficient. That said, the risk remains.

The reality is that supplier chains are built over cycles and decades. Unwinding will be longer term and risky. The major US and European auto supplier chain is dug in like a tick in China. In the old days (pre-crisis), the OEMs and tier one suppliers used to brag about the low-cost supplier strengths in China. Realigning these embedded investments and strategic stakes in China and all that comes with it (IP, tooling, tech, product standards, etc.,) would be a tricky proposition.

The OEMS and suppliers risk excess investment to relocate capacity. That threatens earnings dilution and potentially running the risk of material disruptions. This is a complex area to figure out. We also need to watch which moves ring the bell in US GDP (as opposed to Thailand, Malaysia, or Mexico, etc.). Localizing supplier chains will remain a hot topic. Tariff support (aka protectionism) could be the means to getting it done (see State of Trade: The Big Picture Flows).

The global energy infrastructure issues around crude oil, NGL, and LNG exports takes years of lead time, and entail close cooperation with major energy companies and Europe against the headwinds of the “I hate carbon” constituencies. There are the blocking and tackling areas such as EV charging stations and where utilities, real estate developers, automakers, and policy architects (Federal, local, regulatory, etc.) need to be more efficient. Many of these areas point at growth, but real sustained growth could be beyond 2023.

Cyclical variety is the spice of strife in US economic history the last 50 years…

The US has had some diverse and wild cycles looking back across the decades. The wildest moves occur when there is an exogenous shock (oil embargo, global inflation spike, war, etc.) or the financial system experiences protracted stress that drives a material contraction in credit. Financial asset dislocation can hit consumer confidence and flow into PCE. That was among the Greenspan fears back in 2001.

Some regional implosions (oil patch crisis in the late 1990s, tech bubble implosion in 2001-2002 hitting tech centers) can narrow the impact, but the real pain hits when a combination of major regional, industry, or asset class shock flows into a national level problem. We saw that with S&Ls and commercial banks in the late 1980s and in much more dramatic form for all financial markets and lenders in 2008.

We include the three quarters of 2022 details in the table above to use as a frame of reference in looking back at the annual GDP numbers in the charts below. All the charts use the same BEA data set as explained in Part 2. Below we look at some annual GDP growth timelines for the Fixed Investment accounts.

Nonresidential vs. Residential; Structures vs. Equipment; and Intellectual Property Products as an anchor…

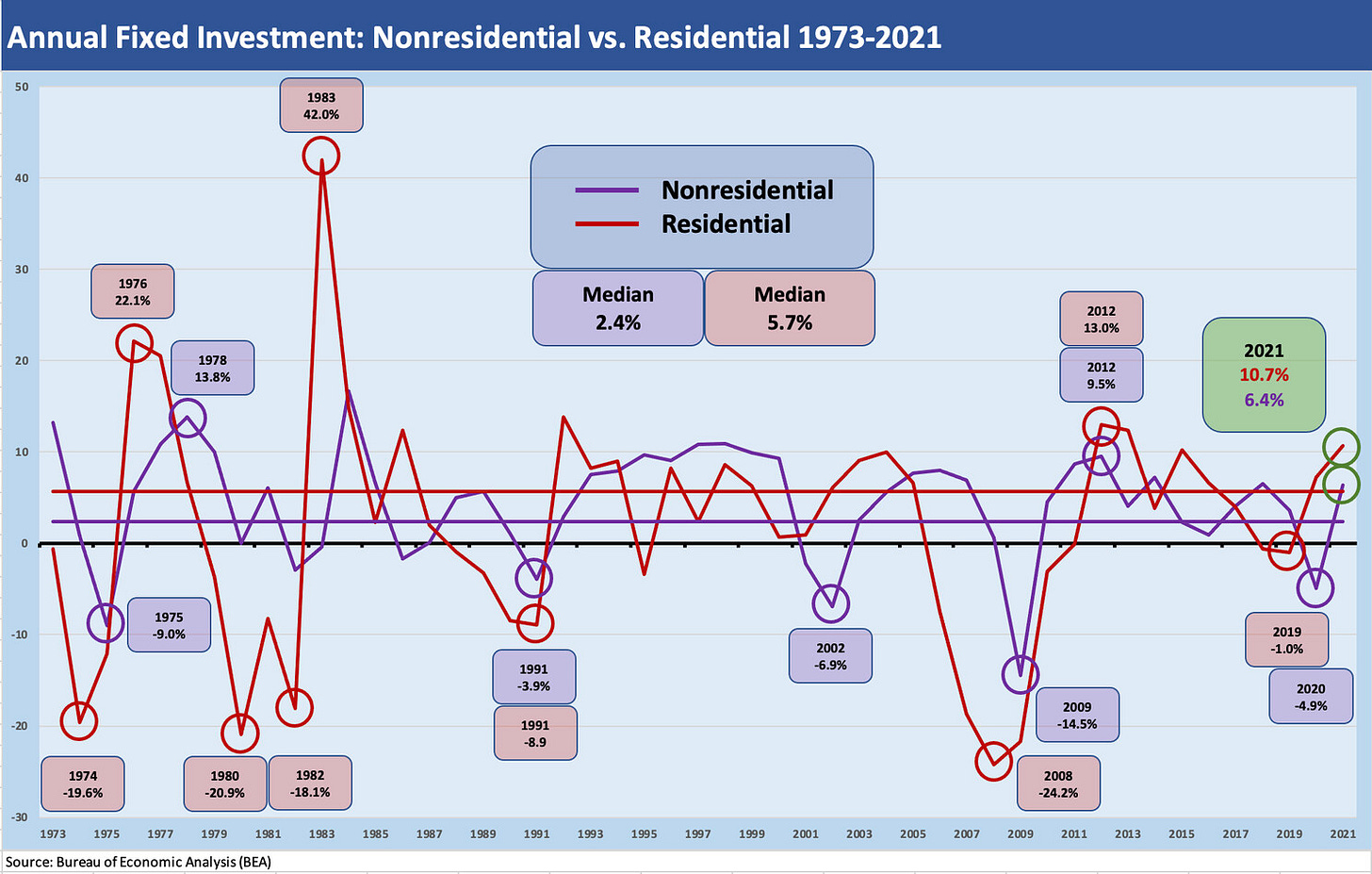

We start with Nonresidential vs. Residential from the recession year of 1973. Both of those lines can really swing wildly across recessions and recoveries as we covered in Part 2. In Part 2, we produced GDP line items for the period during and around the recession years since the 1973 Arab Oil Embargo, across the stagflation years of 1980-1982, and then on across the post-1982 downturns (recessions in 1990-1991, 2001, 2008-2009, and the COVID swoon of early 2020).

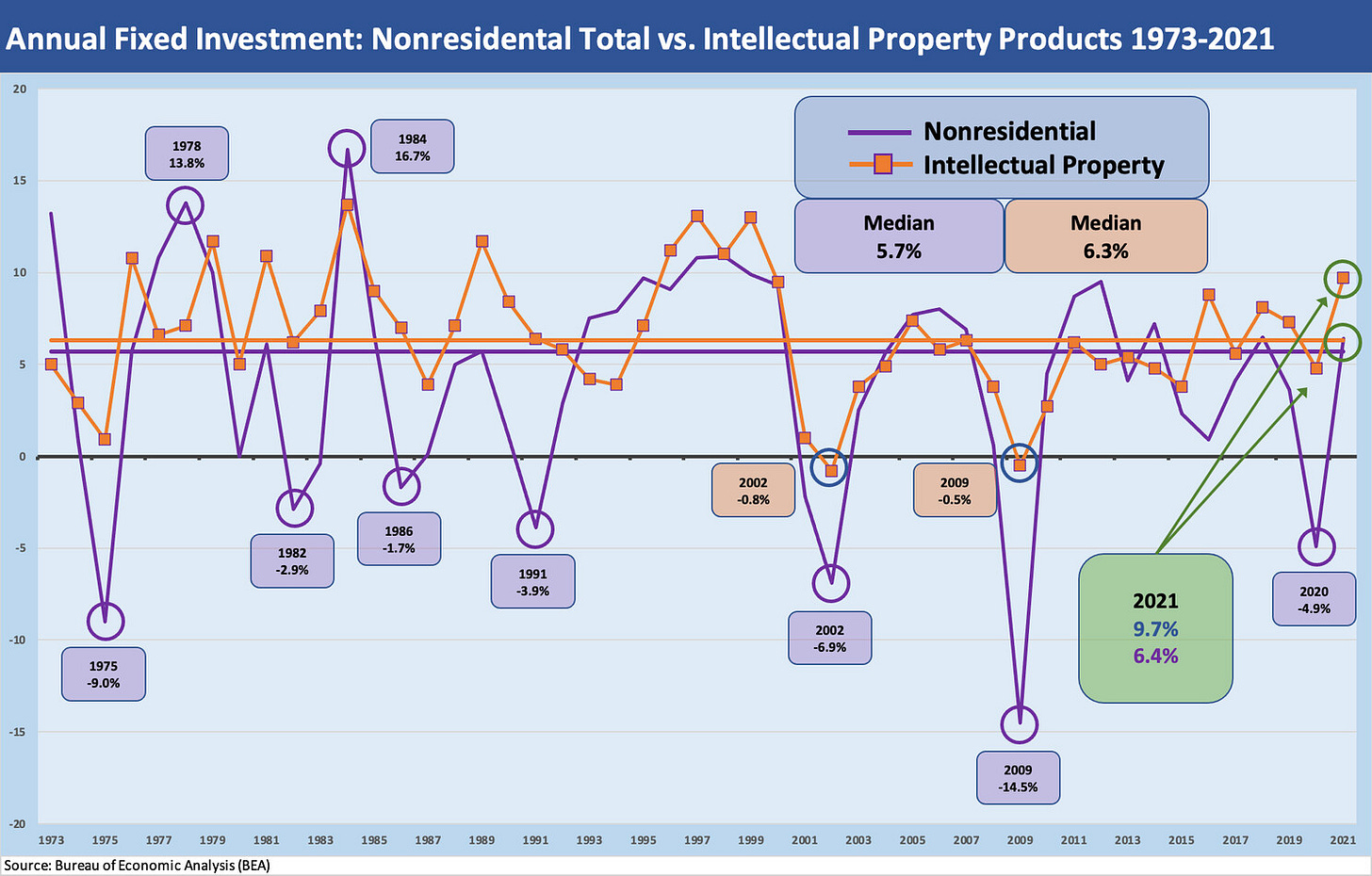

After Nonresidential vs. Residential, we look at the time series for Structures vs. Equipment, where history shows material moves across bouts of cyclical weakness and recovery. We then end with a time series for the much less volatile and overwhelmingly positive growth rates in Intellectual Property Products (IP). We frame the IP growth history against the Nonresidential bucket where IP is included.

The Fixed Investment categories of the GDP accounts is led by the Fixed investment buckets that cut across Nonresidential and Residential groupings. I look at the Nonresidential fixed investment as more or less “Capex” even if not in the GAAP sense. The time series herein offer a history on investment in Structures, Equipment, and Intellectual Property (“IP”), but there is a lot of digging one can do into the underlying details. The categories are (mostly) intuitive. In terms of “GDP share” IP is 5.4% at 3Q22, Equipment 5.3%, Residential 4.3%, and Structures 2.5%. PCE dwarfs them all.

One asterisk would be that E&P drilling is one subsector that rolls up into Structures. Construction, real estate (commercial, heath care, industrial, etc.), new plants, etc., show up here. Machinery and capital goods, non-consumer auto, trucks, and aircraft, and information processing equipment, etc., roll up under Equipment. IP is about a range of line items, but the easy tag is “software” with R&D and Media/Arts categories also in the mix.

The chart details the massive declines in Residential across multiple recessions but a more muted move in 1991 as interest rates were materially lower than in the 1980s. The 1974, 1980, and 1982 stagflation years were deep contractions with only the housing crisis and system swoon of 2008 rivaling those periods. The current 2022 period has elements of the stagflation period but with much lower inflation and all-in mortgage rates than those periods.

Getting into the histories on Structures vs. Equipment tells a story of extreme cyclicality. Both Structures and Equipment have their deeply negative moments, but Structures has the uglier historic profile. The history of “behavior” and investment and lending patterns (i.e., periodic gross excess) in commercial real estate is a matter of record as builders had a tendency to keep building until the market (and lenders) screamed “STOP.” This has been the nature of the builder-beast. I have met risk managers at banks that often diplomatically highlight the need to watch the real estate lending habits on the “revenue side” of the business.

High interest rates take a toll on commercial real estate cycles. The 1980s through early 1990s was a case study in commercial real estate excess with lending going over the top before coming back to bite the asset quality (and in many cases viability) of some commercial banks. Some of those banks ended up seized by regulators from Texas to New England. The TMT bubble also led to plenty of excess space commitments by companies that did not last.

We are seeing some elements of space demands being aggressively pulled back now in the tech space and for many tenants who have felt financial stress from rapid growth strategies that revenue cannot keep up with.

The Intellectual Property line reflects myriad secular trends in automation from industrial applications to almost “everything consumer” with a lot more to come ahead. The IP line only dipped slightly into negative annual growth rates in 2002 and 2009. Those negative growth numbers were less than -1.0% and shows the resilience of the demand for IP across cycles. All you need to do is scan the negative years for Nonresidential and then check out the IP line.

The substitution of tech for labor in so many areas of manufacturing is a broad topic unto itself, and the streamlining of distribution in the services sector from retail to supplier chains just keeps on rolling. The 2002 period was the back end of the TMT crash period and marked a crushing downturn for many companies (including many that disappeared). 2009 was swept up in the systemic bank crisis and deep recession, so both of those slightly negative growth years are explainable. Through 3Q22, we see +6.8% on the IP line.

At over 5% of overall GDP, it is hard to see IP growth being derailed with so much going on in retail, energy transition, energy expansion (e.g., LNG), fintech, mobility, and sweeping changes in supplier chains, etc. The list goes on. The Inflation Reduction Act, CHIPS Act, and the Infrastructure Act legislated over 2021-2022 all support more investment in this arena as well. Further, some of the capex funds that are directed offshore at this point may be coming home to the US. That process is ongoing with a lot of speculation around how much it will grow in 2023-2024.