US Downgrade: Pin the Tail on the Sovereign Ratings Criteria

We look at the latest US downgrade in context of the 2011 action and what it means in the market now vs. then.

The downgrade of the US at this point is more about optics, a fiscal policy critique, and a need to make a statement after the House took default to the 11th hour with more than a few of the extremist elements appearing to desire a default in a “fill or kill” ultimatum.

With a government shutdown likely ahead, the governance issue is not going to have a better look any time soon, but at least a government shutdown does not bring a default.

With the UST market, the worry is not about “loss given default” but “loss given curve shift” if the ability to place record amounts of new issue gets impaired.

With Fitch now downgrading the US to a AA+ from AAA, the top tier sovereign rating is now “2 down, 1 to go.” The news making the rounds now is a much smaller headline development than what transpired back in Aug 2011 as the Eurozone Crisis was in full blaze and risk markets were selling off (the US HY market hit a cyclical peak in early Oct 2011). Higher coupons for UST today are a much bigger problem than the “sticks and stones” effect of not being a AAA any longer by 2 of the Big 3 rating agencies.

S&P took a lot of heat for the downgrade back in 2011. Many in the market (including us) took the view that there really was no objective, long term actuarial history to lean on for empirically grounded default risk criteria when it comes to rating high GDP, developed sovereign issuers. At the time, the downgrade appeared unnecessary. Objective metrics are worse now than during Obama I.

Away from the simple metric of Debt % GDP, the ability to capture retirement benefits (Social Security, Medicare) is not in place for the public sector the way it is for US corporates. A legacy-obligation-adjusted sovereign leverage metric applied to the US would make a 1988 KKR LBO look like a T-Bill.

The 2011 lookback vs. today …

The lack of a clear set of ratings criteria was an acute problem back in 2011 that generated a lot of subjective guesswork. The Eurozone was a relatively new experience at that point, the Emerging Market discipline was rooted in dollar borrowing to reinvest in a local currency economy, and the dollar currency issue by itself complicated the analysis with so many global uses of the dollar (oil, commodities, aircraft, etc.). The term “de-dollarization” is not making the short list of worries yet for most.

Unlike with the S&P downgrade back in Aug 2011, this most recent downgrade by Fitch of the US is more than justifiable after the near debacle on the debt ceiling in 2023. Fitch politely used the word “governance” to capture the flavor of chaos that now seeps out of Washington’s pores.

We even had the former President around the time of the debt ceiling talks saying the US should “do a default” (eloquent as ever). During his CNN town hall meeting, Trump responded to a question on the debt ceiling, “If they don’t give you massive cuts, you’re going to have to do a default.” That about covers the “governance” issue. Default as a strategy runs from the House to past White House residents.

The partisan nature of the default strategy has been affirmed at least for this election cycle. On the governance issue, the rating of AA+ is generous. The Debt % GDP metrics is painfully high, but the governance one is impossible to refute. These are the kinds of subjective criteria that are more defensible in a debate than pure objective financial criteria. When we got pressed to explain the sovereign ratings criteria on the rubber chicken circuit or with clients back in 2011, we had a few soundbites on what a AAA was:

“A AAA security is where investors run when they are frightened, and the UST is thus a AAA. The demand is tied to those assets which offer the benefits of maximum secondary liquidity, and the UST market is the deepest and most liquid in the world.”

Using such narrow criteria, the US is arguably still a AAA despite brutally weak objective debt metrics. There is always the worry of the most extreme bears on UST rates that the rule of “gradually, then all of a sudden” is the main risk. The “all-of-a-sudden” problem was one facing the US in its most recent exercise in debt ceiling brinkmanship. That was also the case in Aug 2011. That threat has been put off until 2025 after the debt ceiling deal. The threat has nonetheless gone mainstream unless the debt ceiling is repealed. Good luck on that. It requires uniform single-party control (hard enough) and a filibuster-proof Senate (virtually impossible for Democrats).

There are other macro issues that are around to debate more tied to market risk. There is always the “dollar will collapse crowd” who are omnipresent in every cycle even if they have to head to the cave for stretches of time. The “China will dump their bonds” thought process is now a much easier sell with Taiwan stress. There is also the move afoot by some nations that are commodity heavy (Middle East, South Africa, Brazil) that are looking to strike arrangements with Russia and China to reduce dollar risk and exposure to sanction side effects. Those are topics for another day.

One issue raised is that the UST credit ratings could lead to a repriced curve that could see a soaring interest rate burden and refinancing needs as it also runs massive deficits. As we saw in 2011, the opposite came to pass and the UST curve rallied. The 2011 worries came against the backdrop of ZIRP and bouts of QE, so we are in a very different world now. Virtually free short UST borrowing in the world of ZIRP back in 2011 was a very different risk.

We are now in a 5% handle T-Bill range with an upper target of 5.5% on fed funds. That is a world away from 2011 in a market with soaring debt % GDP. The failure of the UST to extend more out the curve implies the UST and Silicon Valley Bank risk management team took the same liability management course.

History and Debt % GDP…

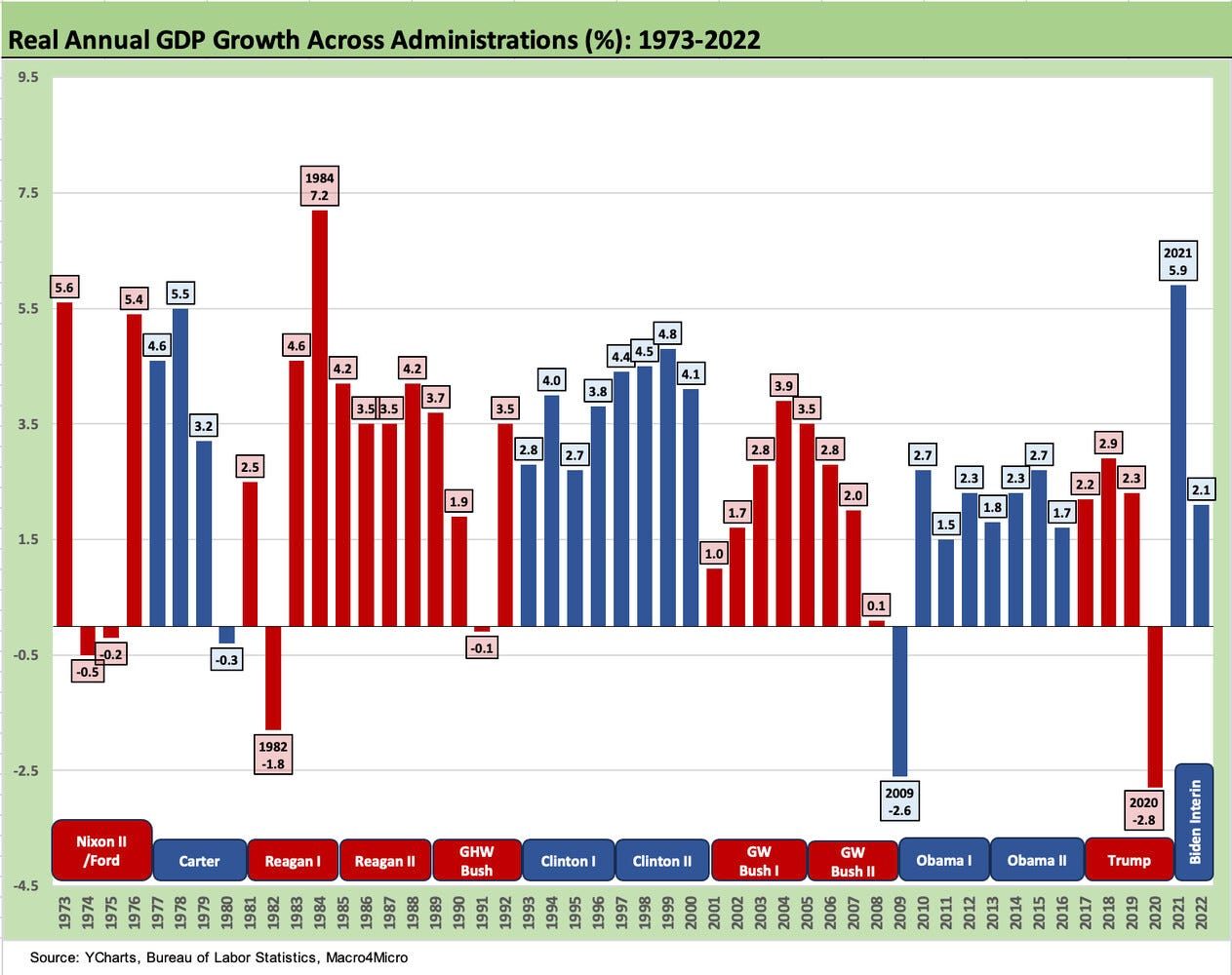

That chart at the top of this commentary looks back across the trend line under various administrations with mixed control of Congress more common than not. We had looked at the very bipartisan nature of the US balance sheet excesses over the past 2+ decades in an earlier commentary. We looked back to the Nixon/Ford years, across Carter, and then into the bull market 1980s and 1990s before the fiscal strains of the new millennium (see US Debt % GDP: Raiders of the Lost Treasury 5-29-23).

We produced that chart from that commentary above as a reminder of “what happened when” and “under which party in the White House.” The takeaway is that the erosion of Debt % GDP is a bipartisan adventure and thus the purple theme.

The 2011 debt downgrade generated a lot of discussion around Debt % GDP metrics as many investors and strategists looked for a magic metric to rely on. Debt % GDP was the main event discussion point. The book “This Time is Different: Eight Centuries of Financial Follies” (2009) became the rage to read, and it became a catalyst for a lot of dialogue.

On the narrow issue of “default risk,” what we took away from our read is that the Debt % GDP ratio that brings on distress and default amounted to, “We have no idea. It depends.” (Our words). I am not sure if they had an “idiots in Congress and self-inflicted wound” weighting in their models, but there is also the myriad sovereign issues of what currency you borrow in, who has the “printing press,” and what sort of problems could be encountered structurally in refinancing and rolling debt. Japan is usually the easy example to counter hard and fast single metrics rules.

The questions we would hear kicked around at the time included some of the following:

What if central banks lose confidence in the dollar and UST?

What if China stops buying or dumps it all as the #2 holder of UST? (China holds around $860 bn.)

The same question for Japan, the #1 holder? (Japan holds around $1.1 tn.)

What if Congress follows through on brinkmanship next time (2025) and decides to “do a default”?

Does this mean that severe dislocations in US sovereign debt are intrinsically a political risk framework and not an economic analysis?

Where the UST wins every time is in its ability to clear the flight to safety bar and secondary liquidity requirement. It would take a lot to undermine that – as in Congress being utterly reckless and destructive. That risk is higher than it has ever been, but that specific creature collection has to go on a default crisis diet until the next Administration.

The more realistic and high probability problem for investors is the repricing dynamics to clear the rising new issue supply and what sort of secondary supply could arise (China holdings) that would bring a adverse UST curve shift.

One of the main points in “This Time is Different” is that high sovereign debt can condemn a nation to low growth. As we detail in the chart above, that theory has been working since the credit crisis. GW Bush was able to print two 3% handle years, and that constitutes bragging rights in the context of what followed with Obama and Trump.

One can argue that the superior growth of 2021 gets an asterisk for COVID rebound effects. That is just logic even if the Democrats would dispute that. For the Trump years, his fans simply say that his term saw the greatest economy “ever since time began” when in fact it was one of the worst shown in the time series. Sometimes just saying it was the best is good enough for some. For them, numbers don’t matter.

Obama and Biden are right there in the slow growth mix along with Trump. If we exclude the two ugly years of 2009 (credit crisis) and 2020 (COVID), the Obama and Trump years give the edge to Trump. Obama II wins vs. Trump’s single term. Unadjusted GDP growth puts Trump as the worst on the timeline. As they say in NBA trash-talking, just look at the scoreboard.

We looked at the post-2008 quarterly mix across the Obama-Trump-Biden years in a separate commentary (see 1Q23 GDP: Facts Matter 6-29-23) that flagged the struggles in the post-crisis economy. The pandemic made for some big swings and renewed activism on the monetary and fiscal side, but it still adds up to the same problem – low growth.

The more complex state of economic affairs in 2023/2024 is tied to how much more intertwined and globalized the world economy has become since the new millennium began. The supplier chain advantages that helped bring unit costs down is now a vulnerability that can drive inflation shocks on supply-demand imbalances. Everyone just took a big bite of that supplier sandwich in 2020-2022 after seeing a lot of chaos on the arrival of more protectionism around 2018. Biden has kept that tariff policy even if he rebadged them.

People tend to forget how young the Eurozone is in cyclical history (Jan 1999). That said, they have no problem remembering the supplier chain fragility that is going to be even more of a challenge given the deteriorating geopolitical relationship with China and heightened uncertainty around Russia and NATO depending on who is in the White House in Jan 2025. “This Time is Different” applies in this case since this time it is much more complex, more troubled, and more dysfunctional.