High-Speed Inversion Gains Altitude

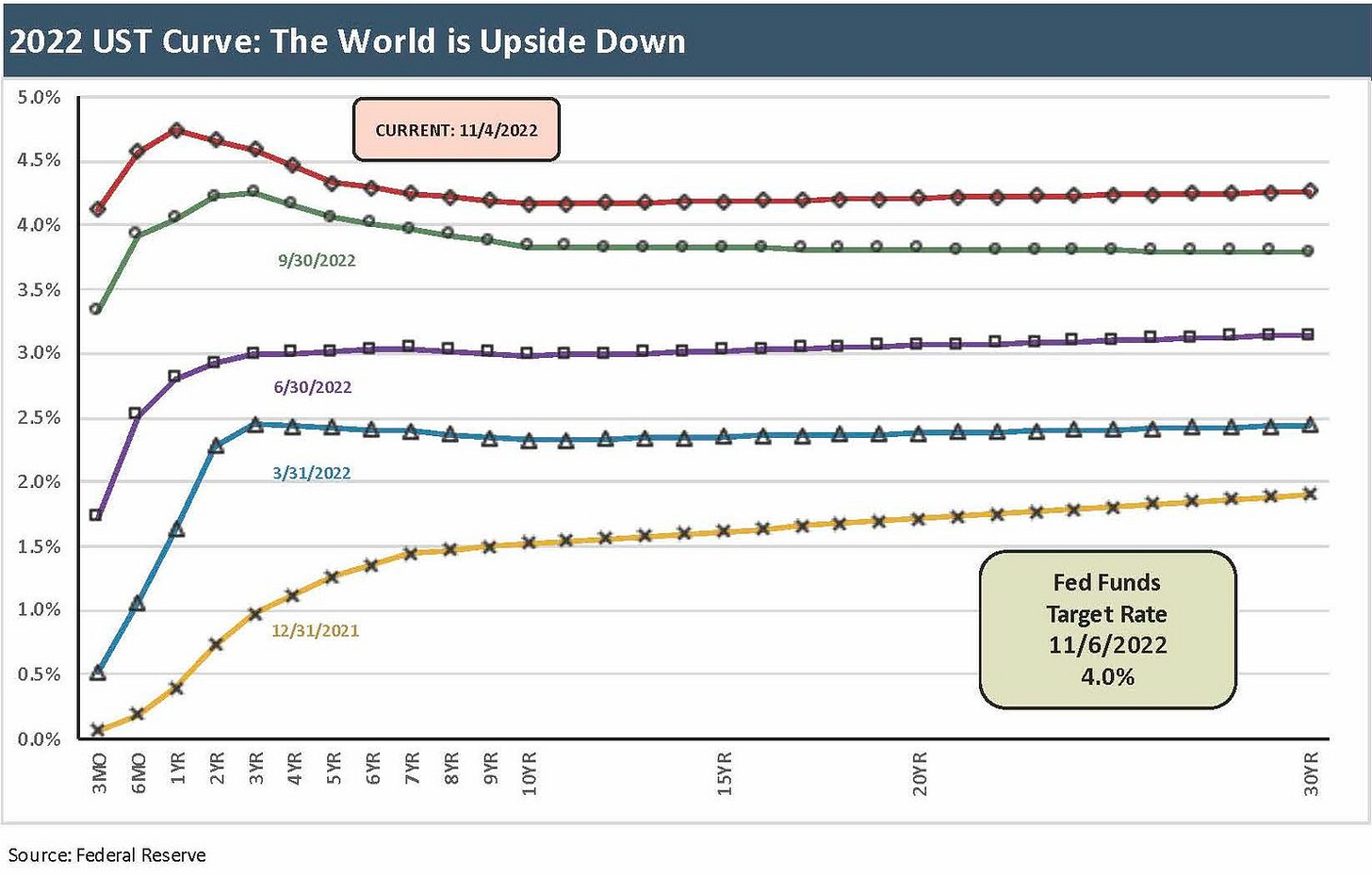

The breathtaking shift of the yield curve is over 4.0% across the board and 4.5% on the short end. Duration pain rules.

Below I include a chart that frames the UST shift across each quarter from 12-31-21 through 3Q22. I also provide an updated UST curve from Friday close (11-4-22). The visual is compelling and is a testament to the speed and magnitude of the shifts all along the curve and not just the front end. With a 50 bps 2Y-10Y inversion to end the week, we are a few bps below the April 2000 inversion and a slightly more inverted than March 1989. As we know, the events that followed those two dates were cyclical weakness, valuation pain, and default cycles (see UST Curves: Slope Matters 10-25-22).

The sort of UST curve whipsaw seen in 2022 has not been seen since the inflation fighting years of Volcker in 1980-1981. Reactions—then as today—go beyond the “bond math” and get into the unpredictable world of shifting expectations around inflation, recession handicapping, asset quality at the banks, consumer finance quality, threats of credit contraction, and the challenges of valuation for long duration assets. The problem today is that much of the bad news is already here, which is in direct contrast with a year such as 1994 when the Fed tightened on speculation of future inflation. Today, investors’ big challenge is grasping where inflation expectations might head and how much worse it may get as the Fed seeks to manage forward-looking views on inflation.

The path of the yield curve in 2022 just keeps the negative return streak going with the GOVT ETF now running in the red. We see bad news for total returns across the trailing timelines including 1 month (-2.9%), 6 months (-6.9%), year-to-date 11-4-22 (-14.1%), 1 year (-14.9%), 3 years (-10.7%), and 5 years -3.9%). Looking back over 10 years, we see a small single-digit positive return of +1.6%.

The performance of high quality, duration-heavy benchmarks show an ugly value wipeout even if the trailing total return record comes with the asterisk that a majority of those years saw ZIRP on the front end. We also have been operating in post-crisis markets with low inflation. In other words, the starting point was low rates on the front end and generally low across the curve. Current market clearing coupons (i.e., cash income) were also running near lows across those years.

In contrast to the low and flatter pattern after 2009 recovery period, we saw a few departures such as the taper tantrum of 2013 and steepening in the immediate aftermath of the 2016 election. Sub 1% intermediate UST yields was a new sight along the way. The combination of post-crisis Fed policy and later the COVID curve still left rates around record lows more than a decade after the crisis.

A lookback at some weird curve years…

I thought revisiting the themes of some earlier wild years for the UST curve might offer some food for thought (2013 and 1994).

2013’s taper tantrum was dominated by psychology and how the Fed’s actions influenced investor sentiment. The parallels of 2013 with today do not work anywhere near as well as 1994 but are still worth considering as it was a time when the market was giving way to high anxiety. Just like today, nerves were very much on display. We certainly saw that during Thursday’s press conference. If we think back to the taper tantrum reaction, the sharp bear steepening (long rates move higher faster than short rates) came on quickly even with the Fed merely considering dialing back QE accommodation (“tapering”). In 2013, the Fed was thinking about buying back less debt while still injecting liquidity and staying at ZIRP. That was hardly a crisis. The overall monetary policy framework was still very accommodative. The real comp is 1994.

The year 2022 has already trounced 1994 on the scale of moves. In an earlier article (see Bear Flattener: Today vs. 1994 and Aftermath 10-18-22), I looked closely at the infamous tightening wave of 1994—one of the more unpredictable post-Volcker years that took place during the Greenspan reign. The fact that the 1994 Fed experience was infamous with only 250 bps of total tightening says a lot about what happens when you surprise the market.

During the Fed tightening binge, I was sitting in my seat at Lehman Brothers with my fingers crossed that Greenspan would not ruin our chances of getting spun off from American Express by the fall. Like most brokers, Lehman was very dependent on commercial paper funding. The Fed did not help on the funding cost front! We were 100% spun off at book value (no pre-spin partial IPO to avoid a write-off by Amex), and the stock dropped like a stone to around half of book. Ouch.

The year 1994 has clearly been surpassed by 2022 as the Fed moved off ZIRP in March 2022 and is now at a 4.0% target with an additional 50 bps expected in Dec 2022. Even if 1994 wins on the sheer surprise factor at the time with no good reason to tighten (2% handle CPI, lower overall than 1993, and early in the cycle), the difference today is that inflation is Enemy #1 right now. Inflation was quickly seen as a non-factor in 1994, so the revisionist history can paint it as a catch-up move by Greenspan after running a steep curve and low fed funds well into the early stage of the 1990s expansion. In 2022, we have serious Volcker-style challenges on our hands, not a 1994-style situation.

Today, inflation has more in common with the numbers when when I arrived in NYC in June 1980 (22% misery index). The worry is that the non-inflation half of the Misery Index equation (i.e., unemployment) will need to move more than anyone wants, and only higher rates can make that happen. That leads many to assume a recession will be needed and a contraction is not just a risk.

The Bull’s hope for early 2023: a preemptive move for a different reason than 1994…

Back in 1994, it was the fear and not the reality of inflation that was the catalyst. The hikes came after a protracted period of easing, and the monetary maneuvers of 1994 were arguably excessive (See Greenspan's First Cyclical Ride: 1987-1982 10-24-22). In today’s language, we could say the Fed’s action were NOT data dependent but more about speculative worries of inflation. The tightening was more a preemptive strike but was quickly seen as “too much, too fast” (aka “wrong”).

As history shows, the year 1995 posted an impressive UST bull flattener. That big win for duration was running alongside a very bullish risky asset rally including the best S&P 500 year of a bullish decade. The S&P 500 total return was +37% after a 1.3% return in 1994. The poor 1994 performance was an anomaly in a bull market decade. HY credit also performed quite well in 1995 at just over a +20% total return after a -1% 1994.

The data dependent vs. forward-looking exercise gets into the “lag” angle raised last week by Powell (See Fed Funds: Language of the Wicked 11-2-22). Just as Greenspan moved to be preemptive on inflation, it was a reminder that Powell can in theory seek to be preemptive around more severe recession risk. That will remain the hope of the bulls. Just as Greenspan acted on a fear of inflation in 1994, perhaps Powell can pause based on fear of a hard landing. The Fed can name their dual mandate song in two notes or less every time. If the Fed opts for the pause, they run the risk that the market will have a temporary reaction and then reject it on the data. That was the case in 1995.

The time-honored debate lives on: When is Fed accommodation too much and when is Fed tightening too much? In the post-Volcker years, history has shown too much easing, running too far into the next expansion. During 1994, the data was on the market’s side and not consistent with the Fed’s worries. In contrast, 2022 has the very murky inflation factors to wrestle with. Inflation is already very high at around triple the 1994 CPI.

Heading into 2023, a preemptive pause to allow lag effects to play out might backfire in reshaping inflation expectations in the wrong direction. The markets could rebound on impulse but at time when wages, oil and gas, commodities broadly, food, supply chain, and employment are still in motion. Those variables have lag times also. With the small uptick in unemployment to 3.7% on a solid payroll number this past Friday, there is still a lot to unfold. The stakes are too high to guess.

The bears expect the Fed to be in the mood to tighten at least until core CPI and core PCE drop. But by how much? Tightening might be “the only way to be sure” (I think Ripley said that in Aliens, but I suspect a mushroom cloud is not the parallel the market is looking for).

A note on the picture at the top of the piece and some historical context…

The picture is from the 1986 movie Top Gun and shows a US Naval Aviator engaging in the sort of US-Russia (then Soviet) relations we see today. Maverick delivers the bird then, but today the US delivers sanctions and weapons systems. Not long after, the Berlin Wall came down in 1989. Ukrainian independence was overwhelmingly approved by referendum (92%) in 1991. Things have not improved apparently.

During 1986, oil prices collapsed to a low of around $10 WTI in the summer, and GDP growth slowed to a 3.5% annual rate after 4.2% in 1985 and a dazzling 7.2% annual rate in 1984. The oil patch was in a regional tailspin for the next two years as waves of bank and thrift failures in Texas brought in more out-of-state buyers. CPI started the year 1986 at 4.0% and ended the year at 1.2%. Regional housing was crushed in the oil and gas patch from Denver to Houston. Those were the days when US regional home price correlation diverged dramatically. That was part of the multicycle inputs that helped RMBS architects botch their subprime models when everything correlated.

Top Gun was released in a midterm election year (so was Top Gun 2)

In honor of an election week, we might as well offer some political facts. The year 1986 was a midterm election year during the second term of the popular and quite conservative President Ronald Reagan (he won 49 states and just under 59% of the popular vote in 1984). He is likely even more popular today with many US citizens who remember days of functionality even with a divided Washington.

Like Obama, Reagan had the virtue of being able to win over 50% of the popular vote in both of his election runs (unlike two-term Clinton who won the 1992 election with 43% of the popular vote and third-party Perot taking almost 19%, unlike two-term GW Bush who lost the popular vote in 2000, and unlike one-term Trump in 2016 and 2020 who never won a popular vote majority). One-term GHW Bush won a majority of the popular vote in 1988. One-term Jimmy Carter won a majority in 1976. Nixon won over 60% of the vote in 1972 and won 49 states. Like Clinton 1992, Nixon 1968 won with only 43% over Humphrey when George Wallace entered on a third party ticket and won 5 states (Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi, Arkansas Louisiana).

To wrap the election topic, the midterm 1986 election saw the Democrats regain Senate control with a net pickup of +8 Senate seats. The House was already in Democratic control and the Democrats picked up a net 5 seats for a 258-177 advantage.