Trade Flows 2023: Trade Partners, Imports/Exports, and Deficits in a Troubled World

We update US trade flows for calendar year 2023 as election year noise will eventually get around to Trump’s 10% universal tariff idea.

With 2023 trade data now released for the full year, we update the trade flow highlights in aggregate, look at some major trade partner relationships, and frame trends across NAFTA/USMCA, the EU, and China.

With Trump pitching a 10% universal tariff on all imports (and threatening 60% on China), there is much at stake ahead for trade risk during an election year in a topical area where Biden should show his mettle vs. Trump, who for his part still falsely claims he collected “billions and billions” from China.

As election year debates get to trade as a topic, we will see if we have two candidates (or 1 or zero) who can articulate how tariffs work and what they mean for economic growth, jobs, and inflation but also frame the trade risks in geopolitical context.

Another risk percolating down the line is the “shut the border” rhetoric and ambiguities around Mexico, the #1 importer into the US during 2023.

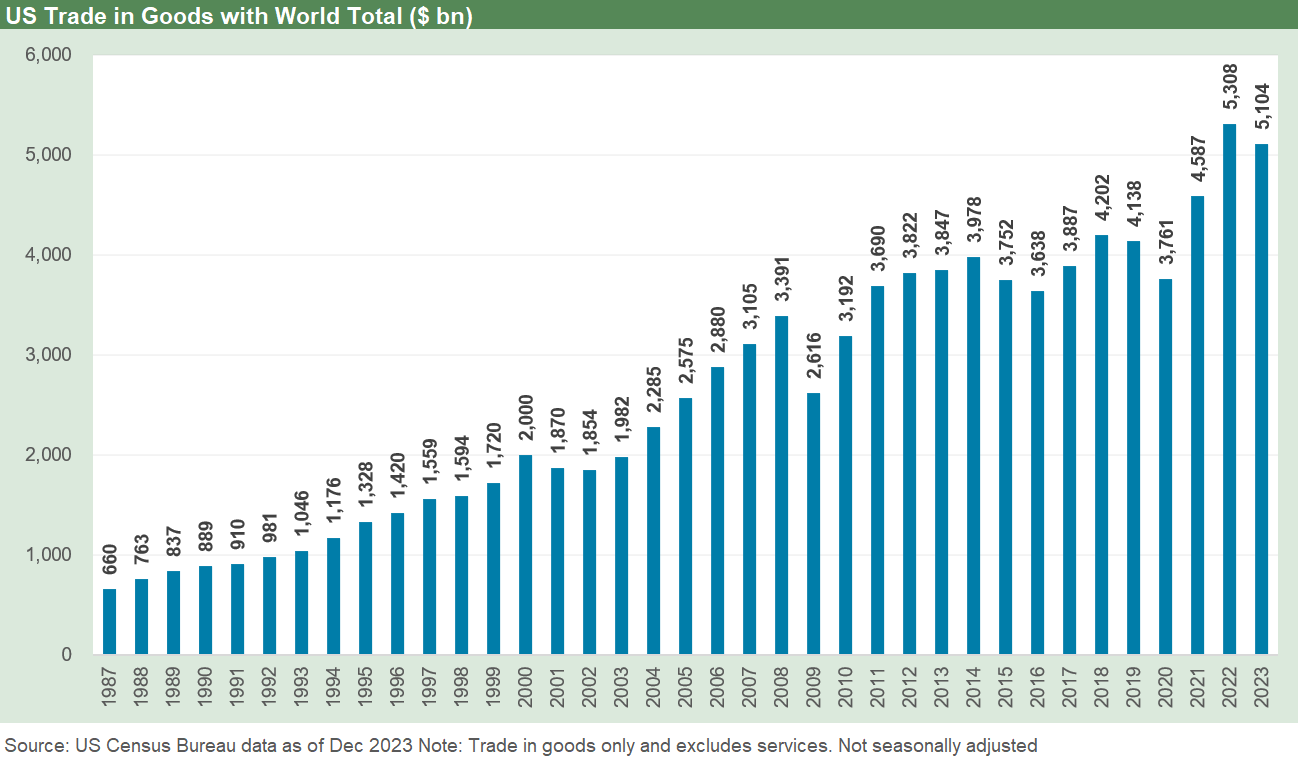

In this commentary, we update the trade trends from calendar 2023, and the news was good on balance with the second highest year for total trade. The year 2022 was the highest and 2021 was the 3rd highest. The year 2023 also posted the largest decline in the trade deficit since the credit crisis but 2023 came with high GDP growth rates and rising employment. That is a good combination.

There are many angles to take on trade whether we look at total trade (exports + imports) or trade balances (notably deficits). One exercise is to consider total trade vs. the narrower topic of trade deficits. The dialogue on trade deficits often fails to consider how that border trade traffic from imports flows into economic activity within borders, especially the US borders.

The story does not end at the border in either direction. Even exports can be part of a NAFTA production cycle that round trips to Mexico or Canada on the way back to the US. Neglect of the significance of the imports is a common problem in the politically driven rants on a trade deficit. The multiplier effects of an imported product’s journey within the US are just as important as the coffers being rewarded by exports.

The expansion of the auto transplant networks in the US is a good example of that effect. When an imported engine from Japan or Germany shows up in the trade deficit, there is the rest of the intra-US supplier-to-OEM chain to consider. The expansion of the supplier chain that received that engine and accompanies that transplant assembly operation does not show up as an import or export since it is already operating in the US near that assembly plant. To take the journey farther down the line, that auto operation’s output can then show up in the export line (e.g., a lot of BMWs from South Carolina). It is never as simple as Trump tried to make it sound back in 2018-2019. Simple-minded is as simple-minded does.

As the election year heats up, the reality of today’s trade flows and new tariff ideas (notably the 10% tariff on all imports proposed by Trump) will be set against the steady stream of disinformation on the results of Trump trade policies. The trade policies of 2018-2019 proved to be one of the weakest points of the Trump years according to a lot of business interests. COVID and the 2020 election chaos blurred a lot of the memories.

Trump’s tariff baton passed to Biden…

The next layer of analysis below the headline trade deficit metric revolves around the product lines. Those details are an important part of framing the effects of Trump tariffs. That includes tariffs that Biden inherited and in many cases that Biden retained even if he “rebadged” some as mutually agreed quota deals. For example, Biden’s team was scrambling to take away the pejorative Section 232 national security labels. As a highly visible union supporter, Biden can still preach his own version of American Worker First.

In the Trump Section 232 tariffs (i.e. national security tariffs), Biden concluded that NATO allies and members of the NORAD command structure did not make for good national security rationales for tariffs. Trump’s trade team missed that connection. Making the world safe for aluminum cans by protecting the US from those that guard the US against nuclear attack (NORAD and Canada) was a new one.

The legacy on the excessive use of Section 232 as national security threats was that the approach got a lot of complaints from mainstream GOP leaders (before they either retired or embraced the increasingly common role of spineless, whimpering, whipped dogs). Democrats naturally complained as well on foreign policy and retaliation grounds.

The GOP threatened legislation to require Congressional approval (Hatch and others), but then they folded. Section 232 tariffs alienated allies, drove retaliatory tariffs, and the whole process promoted caution for investors in the markets (look at the awful 2018 stock markets). Many corporate planners stepped back on capex. The process was ill-conceived and poorly executed, but 2020 and COVID wiped or fogged a lot of memories.

The chart above plots the timeline of import and export growth since the mid-1980s. Sometimes in all the America First dialogue, it is easy to forget that the trade flow issues are highly complex. The topic is not as simple as “I will run on tariffs and pretend it is a frictionless wheel with no other effects. After all, the main goal is power.” The main effect is higher prices to the buyer and either higher cost inputs for US manufacturers and services companies or shows up in the form of inflation in finished goods pricing.

Every bilateral trade relationship has its own set of dynamics tied to product mix, cost structures, and currency variances among other variables. The soaring trade in the 1990s was a function of NAFTA and China’s rise. Both shaped the evolution of global supplier chains and the pace of capacity expansion (or retrenchment) in the trading nations. China as a dominant supplier chain cog is often cited by economists as a key reason for low inflation across the years. That kept rolling into the low rates of the post-TMT bubble monetary framework (Greenspan at 1% fed funds as late as 2004).

Many would say the investment and reallocation of capacity and capex was a material negative for critical sectors such as manufacturing. Supplier chain “safety” was offshored also and that reduced the insulation from geopolitics. That is a setback that has loomed large with China-US tension and uncertainty around the Mexico border problems. The trends also hit labor pricing power (fewer skilled manufacturing jobs in the US and stagnant or declining real wages).

Those negative trends are all true, but setting policy to evolve from here and what policy action the US can effectively execute (and at what pace) without self-inflicted wounds is different than wishing for bygone days. Neither Trump nor Biden materially boosted manufacturing jobs. Biden has generated record jobs growth and notably in such markets as construction and some other key sectors. EV batteries and Semis will be good for the economy, but old school assembly line operations and manual activities still turn on labor costs get fed into the Mexico “labor arb” machine.

2023 trade highlights…

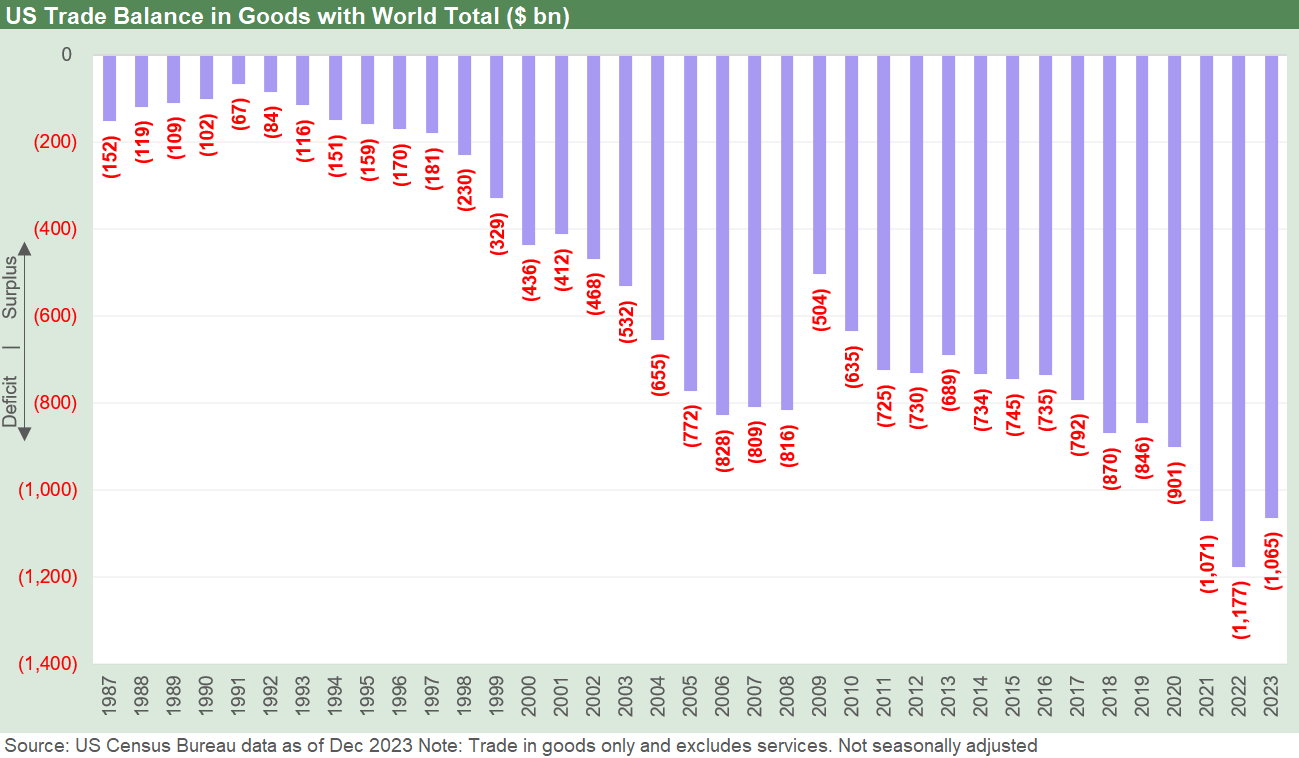

The chart above breaks out the trend in trade deficits. That metric tends to get the most headlines since Trump made it the focal point across his term. It would be interesting to hear how Trump views hitting higher trade deficits in every year he was in office versus anything seen under Obama. The years 2018, 2019, and 2020 surpassed anything in pre-Trump history with 2018 an all-time high and then another all-time high in 2020. That includes the highest deficit ever for his last year in office.

There is a perfectly good explanation for the new highs. Trump just does not know how to explain it or what the moving parts are and won’t listen to those who can (Gary Cohn et al tried but were driven out). A new Trump trade regime would bring more sycophants, errand boys, and obedient bagmen to just slap tariffs on products and nations at Trump’s whim. That is a real risk.

On trade policy and economic impacts, Trump clearly found some of the pedigreed, experienced talent appointed early in his single term to be annoying in terms of their desire to “advise” (an innovative and bold idea for “advisors”) rather than just executing as directed from the top. Then came the purge of expertise (Trump’s version of the “Cultural Revolution” and “Great Leap Forward”).

Trump made trade deficits a cornerstone of his term. That is why Biden should bring it up. If Biden wants to show he is sharper than Trump (the need for such a demonstration just rose this past week), the trade area is one where Biden can show he has a clue. Trade is a good area for Biden since he would have Trump dead to rights. If Biden does not have “the game” to do it, he should let someone else run who does.

The final 2023 trade numbers are easy enough to summarize…

Trade deficits narrowed the most since the credit crisis: The total “Goods and Services” trade deficits declined by $178 billion or 19% from 2022. Including both goods and services, total exports rose and total imports declined in 2023. The goods deficit decreased by over 10% while the services surplus increased with a services bump heavily tied to travel.

To be clear, we don’t see all trade deficits as bad and don’t want to get into a repetition of the basic economics. Been there and addressed that before. Trade deficits are bad when you are not competitive or there are currency-based distortions or unfair trade practices. Where labor unit cost competitiveness is the main issue, then the policy themes are more about power, politics and protectionism.

Outside the econ textbook, reality prevails. This is where economic efficiency principles get served up on the altar of political power. Tariffs to protect jobs are a political decision and not about economic theory. There will be a lot more of that ahead. Biden and Trump both will use tariffs for political ends. Only one of those two (Trump) runs around doing the Mick Jagger “turkey strut” after slapping a tariff on a nation. In other words, tariffs are clearly a Trump ego vehicle. At least Biden will admit the “buyer pays” and catch Trump in his second biggest lie.

Using Trump rules, Biden had a great year in trade: If you are Trump and you believe all trade deficits are intrinsically bad, then Biden just wrapped the last full calendar year before the election with results that Trump himself would call a victory. That would be a good debating point for Biden. He could ask Trump to explain that one. Biden did it in a Presidential term where he had GDP and employment numbers that materially outperformed Trump’s. It would be another excuse to bring this up. These are facts, not opinions.

Tariffs often get sold as a benefit to US workers and a way to recapture the payroll mix that existed before globalization went off the charts (many would say “off the rails.”). Tariffs are more a political tool than an economic tool. Such political ambitions could very well seal the fate of the WTO over the next few years after even more trade battles. That would make for more “no holds barred” conduct with the WTO already unable to function in dispute resolution.

Trump purged the tariff opposition from his party and brought in or converted more so-called conservatives to “blackshirt” status (not a fashion statement). Their role is to be subservient to his policy theme whether tariffs or, more recently, killing immigration bills. Pat Toomey and Bob Corker among others with some backbone and brains are now gone. It is now all about what Trump wants. Trump has even cited a potential 60% tariff on China. That adds a lot of risk to the supplier chain equation.

Materially higher tariffs on China guarantees a trade war, pain in agriculture, and more taxpayer funded bailouts. China might also be encouraged to “restrain” Taiwan semiconductor exports. Trump’s Ag sector bailouts were materially higher in cost than the Obama/Biden auto bailouts. In the Ag sector case, the financial crisis in the farm belt was self-inflicted by Trump’s tariffs. That raises questions of what the House would approve in the future (subject to who has control of the House).

A Democratic House in 2025 could warn Trump “if you slap massive tariffs on China, we will attach so much to the bailout bill your head will spin.” The House will always step up for farmers. They will just pile on with other provisions. In the Senate, someone would have to hold Rand Paul’s hair product hostage to get him to go along. More aggressive tariffs on China are guaranteed to result in massive retaliation on US agriculture. That is a lesson learned (perhaps not by Trump).

Imports from China plunged: As we cover below, China imports also plunged in 2023 and the trade deficit with China was the lowest since Obama’s first term. China import problems are a mixed picture as a challenge and how to deal with it. The China import list is arguably systemic in scale for the US services companies as well as manufacturers from low value-added products to high value-added products. Even with a much lower exposure to China now (the peak China trade deficit was 2018), the geopolitical tension between China and the US is the worst since before the ping pong diplomacy days. The diplomatic chasm has widened and deepened, so the supplier chain threats are worse.

One could easily argue that the politicians in DC could use a trip to the library (not likely) to get their histories straight to better approach and understand the risks involved with China. The bottom line on any good news coming out of 2023 is that the trade deficits and import exposure to China are much lower and supplier chains are realigning slowly but steadily. Reduced mutual dependence of course brings a separate set of systemic risks and long tailed scenarios that are not reassuring.

Service trade surplus increased: Services exports rose by over $74 billion to $1.0 trillion. Travel was a big part of that with an increase over $38 billion. That shift from goods to services cited across the 2023 GDP growth mix has attested to the “experiences over goods” themes since COVID initially saw a goods spike. We focus more on goods than services in our trade work since the US is always ahead in services.

For a sense of scale, the exports of services was $1.0 trillion vs. imports of services of $714 bn. Goods exports were $2.0 tn and goods imports were $3.1 tn. Obviously, goods are the focal points not only given the dollar totals involved but also given the migration of jobs and supplier chains offshore over the past 40 years. That ties back into domestic politics. The US needs more reliable supplier chains. The supplier chain dislocation of COVID sounded the alarm on that.

The threat of deteriorating geopolitics makes the supplier chain situation critical since it takes years to build and unwind supplier chain structures. A more pronounced break in a military scenario would be devastating including inflation effects (COVID proved that), economic contraction, and soaring unemployment. It would not be great for finding UST buyers (or retaining holders such as China) either.

You can definitely get lost in the weeds on the moving parts of trade flows, but the pain gets easier if you remember the potential for distorting effects, e.g. price of oil, in the export and import numbers. The simplest example is that the US runs a material trade surplus with Canada ex-oil. We look at Canada in more detail further below.

Trade issues dominated the 2017-2019 discourse before COVID…

Trade deficits were a very hot topic in Trump’s single term as he was very locked in on the idea that trade deficits ranked among the top problems that the US economy faced. For Team Trump in 2017-2019, NAFTA and China were the biggest problems, but any major trade partner with a trade deficit was a problem.

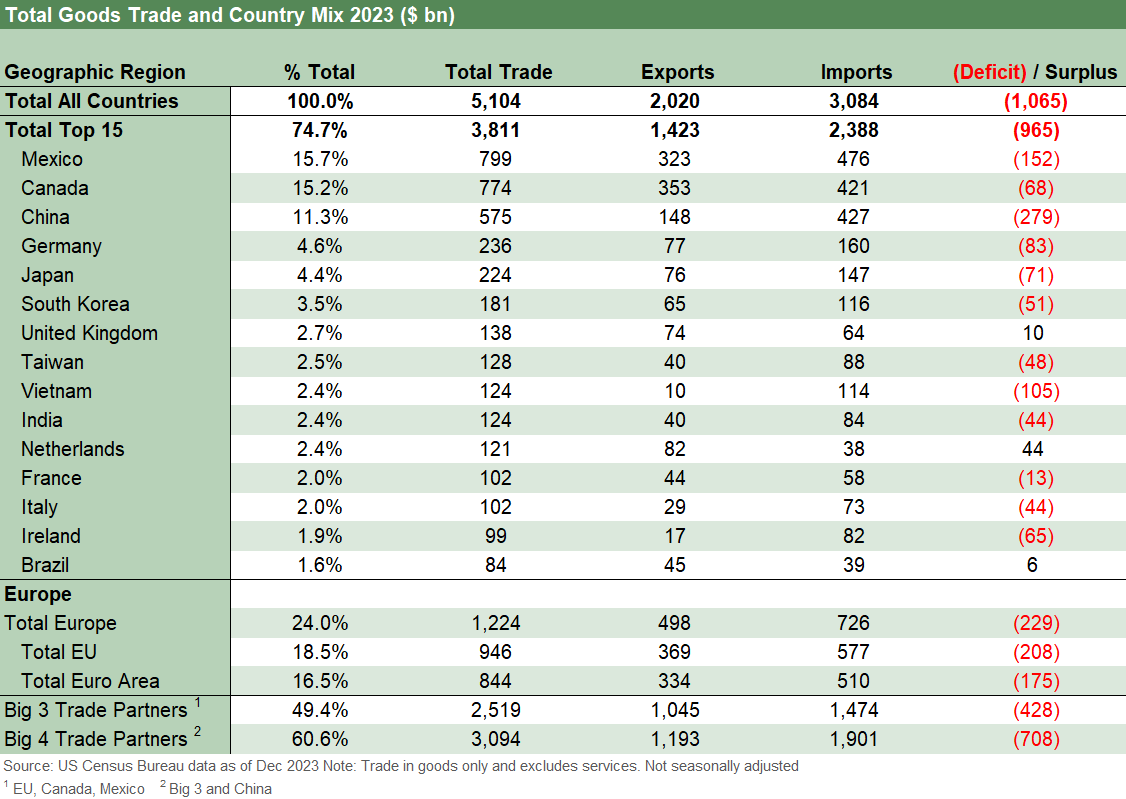

The reality is that 9 of the top 10 trade partners show a US trade deficit including the 6 largest trade partners at almost 55% of total trade (exports + imports). More than 2/3 of total US trade across 12 of the top 15 trade partners post trade deficits. In other words, declaring war on trade deficits was as questionable in practical terms as it was in basic Econ 101 concepts.

What the trade deficit time series details is that Trump generated record goods trade deficits in 2 of his 4 years while Biden has generated record goods trade deficits in 2 of his 3 years. As indicated earlier, all 4 of Trump’s years posted higher goods trade deficits than Obama. Under Trump’s own rules, he failed to correct what he saw as major ills.

Maybe the whole concept requires something more rational now that the single metric soundbites on deficits have proven too simplistic – and simply wrong. Either that, or Trump can just sign a confession of utter failure in trade policy. Confessions are not his thing.

The trade deficit concepts are more complex than the simplistic political posturing…

I am mostly playing devil’s advocate using Trump’s own criteria, but as we have covered in past lives on the topic, we disagree with him on trade deficits as being intrinsically bad – just as most economists disagree with him. “Good or bad” trade deficits come down to the reasons behind the deficits.

The old-time topics of “comparative advantage 101” and low-cost sourcing are at the top of the list of why export/imports have shifted over the decades. Retailers who buy from the highest cost suppliers tend not to last long. Purchasing managers get paid to bring costs down. China opened up a world of opportunities on that front for low-cost sourcing for companies while some were also trying to capture a piece of the China market. The latter did not work out so well. Entire business lines (MROs) have been created to help companies find lowest cost sources for their supplier chain needs.

BAT tax flashback on how tariffs or border taxes can create chaos…

We don’t want to revisit all the strange histories of tariff policies here, but one is worth highlighting. Remember the 20% border adjustment tax proposed by the think tank of Ryan and Brady back in 2017? They were looking for generational fame ahead of Trump’s eventual tax cuts of Dec 2017. That BAT tax was a de facto tariff that would have been painfully inflationary and economically fatal to many companies (retailers went crazy over it). The Senate killed it on the steps before it got in the door. The fact that the border tax would have been an egregious WTO violation did not get much airtime. That is usually the case.

The BAT tax idea assumed the dollar would be so strong after their bill that purchasing power of the dollar would fully offset the tax, so imports would be cheaper and not more expensive. They wheeled out a token professor from Berkeley as “scholarly point man” on the idea. I read some of his work and it was jammed full of ivory tower assumptions, not the least of which was the currency assumptions that would offset all effects.

As the old saying goes, there is a reason that economists don’t have P&Ls. Of course, the dollar rise would be in perfect proportion to all the currencies at the origin points of the products in the import mix. Of course, no US buyers would get hurt with these currency assumptions. And of course, the currencies that seek to shadow the US dollar don’t matter. Or the commodities that are dollar denominated in global trade won’t matter. It was painful.

Basically, retailers indicated they would all be bankrupt and consumers would get screwed. Their lobby groups justifiably skewered their assumptions (which took simplistic to the point of laughable), and the bill was a big waste of time. The Senate crushed it on turf sensitivity and too much grandstanding by House leaders (they just did not say that with their outside voices). The House controls the purse strings at origination, but the Senate likes to control the “spokesmodel” roles. Then the bill we see now came out by Dec 2017.

For US, good economy = high trade deficit

Having a strong economy (or stronger than other major economies in the world) and global sourcing alternatives almost guarantees major trade deficits for the largest consumer market in the world – that is, the US. The biggest decline in the deficits chart above was after the credit crisis in 2009. Lousy economy, lower trade deficits for reasons tied to demand.

The dynamic is not complicated. If demand picks up here in the US, low-cost sourcing volumes surge. Those low-cost sources are often offshore. All you need to do is look at the import list from the nations that have the highest trade deficits. Start with China. The list reads like a trip to a Walmart-anchored strip mall.

Good economies ramp up demand. Clinton’s booming economies and soaring markets in the 1990s hit record goods trade deficits in 6 of 8 years. Growth even in weaker US economies also promises the rising use of lower cost alternatives to support unit costs and profitability. GW Bush and his not-so-great economy hit record trade deficits in 5 of 8 years with 2 wars and a credit crisis going on across those years. The reality in those years was that global supplier chains were still ramping up.

The political spin on “my economy was better than your economy” is an easy debate for Biden to win right now. One of the reasons he should debate early and often (we will look at that topic separately) is that the facts are on his side. The total trade volume (exports + imports) makes it easy to misuse the term “record” since record nominal GDP and record real GDP are not that hard for a leading economy to come up with on a rolling basis as the world grows and the US economy grows. All is fair in politics and conceptually stretched presentations – as long as the factual bar is cleared.

So much of the goods production base has moved offshore into low-cost areas that this deficit is just a recurring feature of the landscape. The only way to reverse it is through protectionism and economic distortion (tariffs and quotas). That is when trade wars break out, supply-demand imbalances and inflationary impacts spiral, and the cascading domino effects on employment and political risk kick into high gear.

That “Tariff Man” strategy by Trump does not seem a like a good one based on history. That is why Trump is vulnerable on these topics. Something has to be done alongside tariffs in the form of fiscal support, and Trump only cut taxes as a “go-to plan” in 2017. That flowed into buybacks and dividends. Then in 2018 Trump was all-in on tariffs.

In contrast, Biden had some stimulus plans other than just tariffs. But he can wave a modified “American Worker First” plan and say (and prove) Trump mismanaged his plan.

Trade partners: a small group dominates the lineup …

Next, we look across the trade partner results in 2023. The flows are dominated by a handful with the EU, NAFTA partners, and China dominating.

The lineup above gives a visual on who the lead trade partners were in 2023. We see the EU at #1 and then the NAFTA partners. We highlight that for purposes of this piece, we will stick with the NAFTA label (vs. USMCA) given the historical importance of NAFTA in the longer-term timeline.

We see how dominant a handful of trading partners are in the bigger picture across the trade line items with the EU, NAFTA partners, and then China before a sharp drop-off to a next tier that includes Germany as a stand-alone trade partner along with Japan and South Korea.

The table above breaks out the Top 15 trading partners of the US in descending order of total trade volumes (imports + exports). The US runs a trade deficit with 9 of the Top 10 (A surplus with #7 UK) and 12 of the Top 15 (Netherlands and Brazil have a surplus). Among notable trends is Mexico moving ahead of China as an importer. That is a sign of the times in China-US trade volume erosion and supplier chain derisking.

If we treat each EU country individually rather than the EU as a single entity, then over 42% of trade is with the Top 3 with Mexico at #1, Canada at #2 and China a more distant #3. The same Top 3 are the top export markets for the US. They are the Top 3 in imports as well. If we look at the EU as a single trade bloc market, then the EU is #1 in total trade and in both imports and exports.

We spent a lot of time back after Trump’s election writing on the trade topic in prior lives since it was clear that this was “his thing” since he wanted to eliminate trade deficits for reasons that requires you skip every economic class known to man.

Firing up the tariff machine and/or canceling NAFTA and beating up China and the EU was his ambition. He got rolling right away and in 2018 struck a deal on the newly renamed NAFTA (not fully effective until 2020) and going hard after China with tariffs and exchanging some mini trade battles with EU countries.

Tit-for-tat tariffs and the high inflationary effects of tariffs was the rule, and fixed investment suffered enough on supplier chain uncertainties that the Fed found itself easing rates in 2019 and specifically citing flagging corporate investment. Major Ag sector bailouts to ease the retaliation effects were the order of the day. Asset performance in the markets suffered badly in 2018 in part tied to such dislocations (see Histories: Asset Returns from 2016 to 2023 1-21-24).

Top export nations…

The chart above breaks out the trade partners by order of US exports (EU as a trade partner) with the related % of total exports. The top of the list is very much like the top trade partner list (exports + imports) except China is a much more distant #4 and the Netherlands shows up in the Top 5. We note that crude oil is the #1 export from the US to the Netherlands. The role of energy in the export lines is getting more important with soaring exports of Energy products from the US.

The energy independence debate creeps into trade…

The Biden team has hamstrung itself in the energy dependence debate since the “carbon sucks crowd” in the Democratic party get annoyed about rising hydrocarbon production. Biden could counter with the fact that the US is not only energy independent, but the US is in fact a major exporting nation with LNG and oil going to ports in Asia and Europe.

Record volumes of oil and gas production and record volumes of exports are an easy counter to the factual misstatements from Team Trump on the topic. The Netherlands did not show up on the top export list at #5 for no reason. The same sharp rise in energy exports was at work in China.

In a debate, Biden could easily call out Trump on why the US is energy independent. It fits on a small index card. Set up debates where index cards can be used. At least Biden will read it, which is more than we can say about Trump.

If Trump thinks we are energy dependent, call his bluff and ask him to ban all oil exports on Day 1 until he can prove we are energy independent in his mind – after Trump defines energy independence criteria first. Then remind him that it was Obama that approved the export of oil. That will send Trump in a visceral state of confusion hearing the word “Obama” while dealing with a fact and doing both at the same time.

Top import nations…

Imports tend to be the most controversial given the dislocations in jobs, offshoring, unfair trade practices, and hourly labor cost differentials that have hammered manufacturing and assembly jobs. We still see the EU at #1, but Canada drops down to #4 with Mexico and China being in their usual role cast as the enemies of US jobs.

Mexico gets tagged as a jobs flight problem (e.g. wages around $4 an hour in auto plants) while China gets pasted with the labor cost issue plus myriad layers of unfair trade practices. Mexican hourly wages are rising at US-owned auto assembly plants now in Mexico given so much light shining on the topic (still extremely low for auto parts) but across a stunningly wide range. Many hardware operations and manual labor-intensive processes had been “offshoring” to Mexico even before NAFTA, and the trend has only accelerated since then.

With China, the IP and tech theft issues (or coercion to cede IP rights) has the effect of compounding the ill will. The Mexico and China issues could overlap as more China manufacturing operations start to move into Mexico (notably a concern in EVs). That would raise some serious issues with NAFTA, and “China in Mexico” already is in the trade rags as a contentious topic. Clashes of the US with Mexico could be more challenging in the future given the direction of politics in each country.

Top trade partner deficits…

The above chart zeroes in on the largest trade deficits by trade partners and also by nation for EU nations on their own. We still see China with the biggest deficit even if well below the peak year in 2018 under Trump (we look at China in detail further below).

Some of these deficits are with countries that have a massive base of operations in the US and NAFTA region. Some do not. The multiplier effects in other industries should be considered in looking at these numbers (supplier-to-OEM chain effects, trade and finance, retail, and dealer effects downstream, freight and logistics and US services side benefits, etc.).

The most interesting name on the list is Vietnam at -104.6 bn. That trade gap offers a reminder that reducing deficits in one country does not necessarily yield reshoring in the US. In the case of Vietnam, some of the deficits with trade partners such as China simply saw some changed addresses with the import moving over to another low-cost nation.

This is where some of the pushback comes in with the idea that “all deficits” are bad. In the case of Germany and Japan, there are massive transplant operations in the auto sector. That means supplier chains at home (or finished vehicles such Daimler and BMW) feeding into US operations. The presence of Japan and Korean transplants across the US (notably in red states) does not need much explanation. They are positive factors for states and the US economy.

That transplant manufacturing presence brings waves of economic activity across freight and logistics services (port, rail, trucking, warehousing). In addition, many other suppliers relocate or expand operations in the US to be closer to the transplant assembly operations.

Retail, finance, and insurance are a standard part of the chain as well. It is all accretive to the economy even if an increase in the net trade deficit line is a deduction from GDP. These other operations drove growth in other lines in the economic releases.

The proportionate mix of imports vs. exports can be held up to another metric also. Trade deficits as a % Exports matters more to those who see it as “bad stuff divided by good stuff.” We don’t see it that way, but the ratio offers a metric that sizes up the trade relationship.

Vietnam is an extreme case with the ratio at over the 1000% line. The US had quite a bit of non-trade exporting going on with Vietnam in prior decades, but now we have a healthy trade relationship. The interesting twist in the trade volumes with Germany, Japan, and Vietnam (where the US had some 20th century disagreements) in today’s global economy is that one would hope things can get better in reaching some constructive balance with China and Taiwan. So far, not so good…

Every country or trade partner on the list can be peeled back to the underlying product groups in other exercises, but it is notable that the NAFTA partners are not on the list. China is high on the list while Germany and Japan made the lower end of the list.

We review the export and import lines periodically to frame where the lead product groups are. We reviewed them again for this piece and looked at the major trade partners. The most striking changes are the steady increase of US crude oil and natural gas exports over the last few years.

In debates, Biden may benefit with independents if he highlighted the record oil and gas production and demonstrate that Trump is making up his own facts (nothing new there). This could be viewed as showing balance with the climate initiatives while proving Trump a liar to independent voters (the MAGA base is fact free and too far gone).

Trade flows with the Big 4: China, EU, Mexico, Canada.

We wrap with a closer look at the biggest trade partners. We start with China since that is the riskiest piece of the story line in trade policy. The supplier chain exposure risk has been discussed constantly in recent years along with the growing geopolitical stress. This is where the cracks can widen into a major problem. That is obvious.

If Trump is elected, the EU could be the next major risk and especially around areas such as tariff policies, Trump’s view on auto trade deficits, his willingness to invoke Section 232, NATO budgets, and Ukraine side effects all make for tough relationships with Trump and the EU (ex-Orban). The state of affairs is generally just poor relations with EU leaders that Trump thinks do not respect him or trust him (an accurate assessment).

Mexico will also have its issues given the leftist drift of the Mexican government, the immigration and the wall issues, and the desire of more than a few in DC to attack cartels with the US military. That all can be a “strain” on the future of this relationship.

Threats of “closing the border” (murky term) were headed off by advisors in Trump’s first term, but that “close the border” phrase can be used literally as it was under Trump. Recent opinion columns in the Wall Street journal flag anxiety over the term being used in the broader term of locking down the border entirely from time to time. That would be very disruptive to supplier chains even over the short term. As a reminder, Mexico was the #1 importer in 2023.

Mexican trade deficits include a lot of production capacity owned by US enterprises, so that trade deficit issue is a tough nut to crack. There might be no guardrails on Trump (at least that he would pay attention to) on looking to “cancel” his NAFTA/USMCA deal if he does not get his way. He raised that in his last term as well. He voiced his willingness to unilaterally terminate NAFTA during his last administration and battled with his more substantial, seasoned advisers. They will not be around next time.

China trade always an adventure…

China has been a wild ride with imports peaking in 2018 at over $540 bn. The chart below plots the long-term timeline with the last 5 years in the box. The breadth of the imports from China is extraordinary. We will drill into those in separate commentaries. TMT equipment is #1, computer equipment #2, and toys a more distant #3. Batteries are also materially higher over the past 2 years.

The lead exports from the US to China are soybeans at #1 and crude petroleum at #2 followed by Pharma, Semis, and Aerospace at #3, #4, and #5, respectively. Among notable declines in the Top 10 exports are semis and aerospace in recent years. Natural gas is also rising.

The China piece of the trade flow puzzle is not going to get any easier in 2024 with all the geopolitical tension and election year posturing. In past cycles before the credit crisis, there was little to rival the import growth of China as more US companies were standing in line to operate there.

Low-cost countries (“LCC”) became an acronym in US and European company conference calls and presentations. For many auto suppliers before the Detroit 3 melted down, some suppliers would have slides dedicated solely to their initiatives in China (it was inevitably a joint venture). It was part of the global growth sales pitch.

The trade deficits with China got a lot of airtime during Trump’s single term. Since then, the relationship with China continues to get worse and more geopolitically tenuous around Taiwan and technology.

Team Biden can generate some supportive numbers around his approach to China in trade since the trade deficit is lower. The -279 bn trade deficit is the lowest since Obama’s first term. That can be Biden’s pitch. Exports to China in 2022 hit a new high with a modest sequential decline in 2023. The reality is that the top export lines to China have easy substitutes for China in the form of soybeans and oil.

The above list just breaks out the total trade (exports + imports) deltas in 2023. We included this chart here since the biggest swing is in China while the EU moved higher. Changes in trade totals can be a function of either exports or imports and can be tied to price (e.g,. oil) or volume. That gets into the next layer of the analysis by product line. That is for another day.

The EU as trade leader…

The frustration for Trump and his trade team around the EU was that he had to deal with the EU as a bloc and could not engage in bilateral beatdowns. Peter Navarro (of “Green Bay Sweep” failed coup fame) tried to attack Germany early in the game (while visiting) and got nowhere. He complained the implied Deutschemark value was unfair. His thesis adviser at Harvard continues to spin in his grave. Pushing the French too hard is always doomed. Italy simply does not buy much from the US. The US has trade surpluses with the Netherlands and UK (no longer in the EU).

That mixed trade picture by EU and non-EU European nations makes for an unwieldy strategy. Tit-for-tat tariff exchanges were a recurring event during the Trump years and there are still various ongoing tariff discussions (e.g. steel and aluminum). After the economic setbacks of 2018-2019 during the Trump years, we expect the EU and China tariff strategies could “evolve.” The tariffs of the earlier battles most certainly cost taxpayers a lot in bailouts of the Ag sector.

Attacking the EU is less systemic in its threat while China will be that much more of a challenge with the Taiwan issues that much further along and higher on the toxic scale. Trade weapons at China’s disposal would be more potent than in 2019 if we see a material escalation (picture a broken supply chain across medical supplies and pharma). China could play hardball with Boeing, who has enough problems right now. The EU is winning the airplane battle at this point with Airbus over Boeing, so it can find other forms of retaliation of attack with more tariffs.

The EU has a lot to aim at in the US, but they have been very measured in past battles. They even targeted the home states of GOP leaders (cranberries in Wisconsin for Paul Ryan, bourbon in Kentucky for McConnel, orange makeup paste for the White House, etc.). The EU is always going to respond in proportionate manner. They take a bureaucratic approach.

The balance of trade deficits with the EU is broken out above across time. The good news for the US is that energy exports to the EU are rising and will continue to rise whether in crude oil or LNG. There is a lot of tension in steel markets and aluminum. Trump’s expectation that Germany should (or would) buy more US cars was just silly and embarrassing. Of course, Germany will buy US-made Mercedes and BMW from the transplants.

The Trump administration moved forward on a review of Section 232 for autos during Trump’s single term. In the end, it did not happen, and the administration refused to release their rationale for Section 232 national security tariffs on autos (making Greenwich CT safe from German cars?).

The report on the topic was never issued. The rumor was that the Section 232 report on autos as a national security threat was so dumb it was funny. The Trump team would not release the report and invoked executive privilege. According to a report on the subject from the Department of Justice’s Office of Legal Counsel (DOJ):

“The President may direct the Secretary of Commerce not to publish a confidential report to the President under Section 232 of the Trade Expansion Act of 1962, notwithstanding a recently enacted statute requiring publication within 30 days, because the report falls within the scope of executive privilege and its disclosure would risk impairing ongoing diplomatic efforts to address a national-security threat and would risk interfering with executive branch deliberations over what additional actions, if any, may be necessary to address the threat.”

You don’t see that every day. It can be paraphrased using an overused expression: “I could tell you how dumb this whole idea was. But then I would have to kill you.” Given the desire for Presidential immunity, that last part is not so funny these days.

Trade with Mexico…

The above tracks the history of trade deficits with Mexico, and it speaks to how much activity NAFTA generated since inception. We detail the past 5 years in the box below for both the import and export line. The pattern with Mexico is like Canada in the direction of dollar volumes of imports and exports steadily moving higher. The increases in economic activity are not hard to see as positive for growth in business on both sides of the border. You can always ignore that for political purposes.

The downside is around the reallocation of jobs, and that becomes a major political factor that riles Trump with his opportunism bells going off and Bernie Sanders with his concerns around the American worker. Unlike Trump, Sanders never had an opportunity to do anything about it. The combination of North American and US content requirements brought a boost to investment for the highest visibility sectors, but cheap labor for manual activities has continued to favor offshoring to Mexico.

Autos and parts and computer/electrical and various equipment categories dominate the Top 10 of the Mexican import story line with a slice of crude oil. For exports to Mexico, refined petroleum products is a clear #1 since Mexico is short refinery capacity despite their oil riches.

We also see a lot of material and component inputs for manufacturing operations in Mexico heading south as exports from the US before doing a round trip as finished goods or larger component system imports. That is very much a part of lean manufacturing strategies used by US manufacturers. Disruptions of such supplier chains carry risks.

The Mexico line is always a tricky one with so much two-way traffic across borders into and/or out of the Mexico supplier-to-assembly chain. The supplier chain can run the gamut from high quality flat rolled steel to commodity-like components to higher tech integrated component systems. Those inputs can originate in the US, China, Japan, or Europe before they make the journey to the US for final sales. The same is true in many tech operations. Low-cost labor (very low-cost labor) in Mexico has been the hook in planning for North American capex allocations for decades from computers to cars and across numerous manufacturing chains.

Mexico could also be on the receiving end of the “friendshoring” trend (as opposed to “reshoring” trend) that is looking to derisk excessive China supplier chain risk. Lowering such costs via Mexico would reduce risks associated with the effort to return more semiconductor operations to the US through more greenfield investment.

The situation with semis is precarious if geopolitics go the wrong way. That predates Trump and long before Biden. Obama did nothing and Trump did little except make noise. Biden’s CHIPS and Science Act, which some Trump allies in the House actively sought to undermine just as they did with infrastructure programs, is a belated start in protecting US semiconductor needs. What was wasted on the trade war under Trump and in the resulting Ag bailout that came with tariff retaliation could have been deployed to domestic incentives in semis.

The theory is “the more regionalized near the US the better.” The challenge is to keep unit costs down by the end of the line in the supplier-to-OEM chain. To the extent that is not favorable, that is when tariffs get deployed to artificially shift the economics of production and relative competitiveness.

Trade with Canada…

The above chart shows the swings in the trade balance with Canada while the next chart looks at the historical pattern of exports and imports with the last 5 years of imports and exports detailed in the box. Canada is a much different situation than Mexico even if both are part of the same updated version of NAFTA.

As noted in the charts, trade flows stayed strong in 2023 with year-to-year moves being influenced by swings in oil prices and especially how that impacted oil trade with major trade partners such as Canada in 2022 and 2023. The US also got to the point in 2023 of record oil and gas export volumes but it remains a major importer of Canadian crude oil grades that are very much desired by the more sophisticated, advanced US refiners that can process heavier crude (notably from the major Canadian oil sands players). The US also exports substantial volumes of refined petroleum products and crude oil to Canada.

Canada is likely the best trade partner the US has. The US runs a healthy trade surplus ex-oil. When you look at the product mix of exports and imports, the US moves a lot of high value-added products north across manufactured goods in categories such as autos, aerospace, commercial vehicles, construction machinery, and computers. The round trips back and forth across the border for autos, parts, and materials is hard to generalize about, but it is part of an integrated manufacturing system that includes the Detroit 3 and Japanese transplants.

The mix of energy trade across crude oil and refined petroleum products can vary substantially and confuse the issues. Canada shares a lot of the US political dysfunction around fossil fuels with the upstream sector in Alberta not getting along too well with the coastal provinces on such topics as pipelines.

As noted earlier, the oil sands players’ main target is the US and especially the Gulf refineries. They lack the scale of access to tidewater with pipelines to materially increase global trade flows relative to production capacity (even with Trans Mountain expansion). The flow of more heavy Canadian crudes to the US in the future would simply change the planning of domestic vs. export volumes of other crude grades produced in the US.

A major question is whether Trump would seek to apply his universal 10% tariff on oil imports as well if he opts for a “drill-baby-drill” program in the US at the expense of Canada. That would take a NAFTA lawyer to explain if he could even get away with that. Even then, Trump is not shy about dishonoring contracts or sovereign agreements.

In his early days of his tariff mania, that idea of taxing oil imports was on the table (I looked at one of the lobbying pieces working against that idea). Such a plan would be intrinsically inflationary. Regardless, Trump would get more retribution psychic value points out of not doing that and simply approving Keystone extension projects again instead.

You never know since Trump’s tariff plans are “underdeveloped.” As a reminder, there was no GOP platform in 2020. None. We would not expect one in 2024. Trade will most likely be a matter of the moment and a function of whims and which leaders annoy him. Canadian liberals/Liberals tend to annoy him (whether small “L” or by party name).