Inflation: Events ‘R’ Us Timeline

We detail the event history for inflation from the 1970s/early 1980s stagflation and across the post-Volcker years.

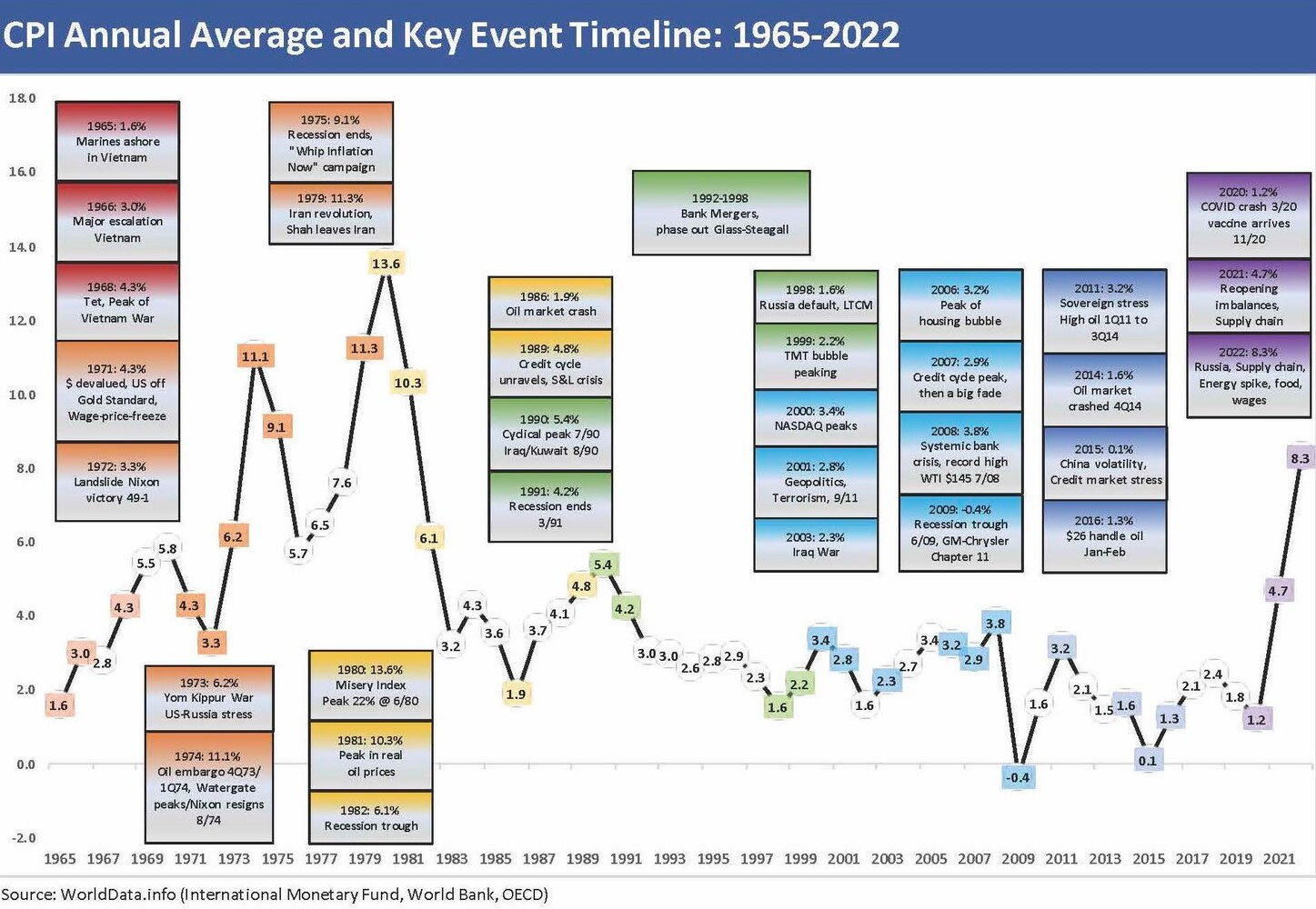

We constructed a chart that looks back across the decades to detail critical events and market highlights. The history runs from the Vietnam War and then on across the business cycles, booms, busts, bubbles, crises, and pandemics. We plot the CPI against those backdrops as a reminder that every cycle was quite distinct. Pivotal events have literally shaped the UST curve across time, set the stage for Fed policy actions, at times placed demands on legislators, and often distorted pricing in the markets for goods and services.

Key Takeaways

Oil was big in the stagflation years, but not the whole story: There is no question that oil shocks were the dominant variables in the 1973-1975 recession and the 1979-1981 period, but there was a lot more going on across industries and inflation as regulatory changes unfolded and consumers fought for wage increases along the way. Oil dictated structural change, consumer preferences, accelerated operational and financial restructurings, and caused more than a few bellwether names to disappear. The story still extended beyond OPEC and oil shocks.

Events matter: While the focus on oil is for very good reasons (I remember being in odd-even license plate lines at the gas station in my high school years), the years of turmoil in Vietnam, wage-price freezes/controls, and the economic policies leading into the October 1973 Arab Oil Embargo also set the table for sustained inflation pressures. The waves of challenges included the Vietnam inflation years after 1965, on through the Nixon wage-price controls in the early 1970s, across President Ford’s “WIN” campaign (“Whip Inflation Now”), the Iranian crisis and new oil shock of 1979, and the arrival of Paul Volcker in August 1979. The pressures and headwinds called for drastic action – and then even more “events” were driven by monetary policy.

Vietnam as a starting point: When economists or commentators frame the “Great Inflation” they often start in 1965 for a reason. That was the year the Marines waded ashore in Danang, in turn formalizing (sort of) what had been an advisor-heavy expedition. 1965 saw the last 1% handle CPI number, and that level was not seen again until 1986 when oil crashed following years of Volcker inflation fighting. The challenges of Vietnam gave way to the “other twenty-year war” – which was inflation. The peak of that inflation war came in 1980-1981 with a few bouts of 20% fed funds., which swung wildly as it floated across a period where the Fed policy focus was on monetary aggregates. We will discuss a range of other periods and policy actions in other commentaries along the way.

Oil shocks: The fact that oil shocks are a focus today in framing inflation histories is that oil and energy dependence was such an overriding factor back in the 1973-1975 recession. The same was true when the oil markets spiked with the Iran crisis in 1979. At the time of the first wave in 1973-1975, that recession (Nov 1973 to Mar 1975) was the longest (16 months) since the Great Depression, and oil was the key driver. The role played by wage-price spirals and the pent-up economic forces distorted by the wage and price controls is a tough performance attribution exercise to sort out. The currency issues after exiting Bretton Woods only added to the complexity.

Oil and the 1980-1982 double dip recession: The second leg of the recession (Jul 1981 to Nov 1982) tied the earlier 1973-1975 recession at 16 months, so in less than a decade we had the two longest postwar and post-Depression recessions. That second leg of the double dip was on the heels of the 6 months from Jan 1980 to Jul 1980 in the first leg. The double-dip is a reminder not to get caught up too much in the “recession” date designations since 1979 was also an inflationary disaster that did not yet qualify as a recession since it did not bring GDP contractions in any quarter. To many of us, the period from later 1979 to 1982 felt like one long recession.

The Nixon tumult: We are not referring to Watergate but to wage-price controls and going off the gold standard. The fact that the Arab Oil Embargo was announced the day before the Saturday Night Massacre of October 1973 is a political coincidence, but the timing helped neither the national mood nor Washington mindset. The tension in the world was a lot like today with the US and Soviet Union perilously close to a deadly clash in the Mediterranean during the Yom Kippur War. Nixon put the military on alert. Geopolitics saw some literal DEFCON 3 and DEFCON 2 moments during that time frame. That was the worst series of events since the Cuban Missile Crisis. It gets very little “ink” in the lookbacks at the period.

The inflation victory of Paul Volcker: The brutal 1979-1982 policies beat inflation down and overhauled many industries. Whether one declares victory over inflation in 1982 or waits for the next 1% handle CPI to match 1965 (occurred in 1986) is a subjective debate. The Volcker policies saw fed funds explode past inflation, and his policies will raise questions even today around where fed funds should be relative to inflation (headline or core). Median fed funds ran higher than CPI in the years from 1972 to 2007 (35 years), and the relationship flipped after the 2008 credit crisis and into the COVID period in the age of ZIRP and QE. How and when that will revert (or not) to the pre-2007 relationship in the current inflationary, tightening, and QT market is a discussion point we will also look at.

The Greenspan regime took over in 1987: The rest is literally history as laid out in the chart. The gradual move away from fixating on monetary aggregates during the remaining Volcker years and later toward transparent fed funds target ranges was the main story on the monetary side. I remember the Lehman 1980s days when people would await the money supply data and the “Fed watcher” would get on the trading floor box. Things have changed. The Fed had its hands full given rapidly changing capital markets, waves of disintermediation of the banks and loans by bonds, the rise of mutual funds as lenders, and protecting financial stability. The subsequent years saw record long recoveries and market booms interspersed with crises of asset bubbles and lending excesses. The Fed’s job is never easy and new “events” keep it that way.

We will spend more time in these time periods, Fed policy actions, UST migration patterns, capital markets swings, fundamental economic and industry trends, and financial system pyrotechnics in coming charts and commentaries. The goal is to find applications to today and do a little compare-and-contrast to avoid oversimplification (a constant challenge in research these days).