The Cash Question: 3M-5Y Yield and Slope

We review the 3M-5Y slope, the cash penalty, income opportunity costs, and reach for yield. Cash is in comeback mode.

Summary

The 3M-5Y UST slope is important in framing risk appetites as the “penalty” for cash shifts. Similarly, the reward for extension out the curve shrinks in a flattening/inversion and reduces the incentive to take more credit risk or duration risk. That decision comes down to your view on the pace and scale of UST migration and cyclical fundamentals. Right now, cash is looking good in the risk-reward equation when framed vs. bond and dividend yields. If the investor wants to take less curve risk but likes credit, leveraged loans or BDC equities and other products are part of the debate. With fed funds at a 3.25% target and expected to easily get north of 4% by year end, the plot thickens for those who are not asset class constrained. Those who desire an income flow but remain bearish on equity market price risk and duration need to consider whether this year will be like 2018 and 1994. The question is will cash keep winning the performance contest? My own personal preference under the “money where your mouth is” rule has been for a semi-active mix of cash, loans, BDC equities, REITs, and energy. It does not take long to push buttons and wade back into more equities or credit after a cash build.

In this commentary, I look at the front of the UST curve from 3M to 5Y. I look at the slope and the absolute rate history for those two maturities. The goal is to highlight the migration of yields across the timeline covered and track reactions to various economic expansions/recessions, the array of credit cycles, some extreme bouts of systemic stress, and how the shifting monetary policy across those periods flowed into rates. With interest rates rising quickly in 2022 and everyone talking about comparisons to 40 years ago, some historical lookbacks are in order. We are seeing nominal yield numbers in short UST and 5Y UST that hearken back to pre-crisis periods.

In the above chart, I show the yields individually for each of the 3M and 5Y UST since 1984. I use basis points for this chart rather than yields since the numbers got down to double digits after the credit crisis of 2008 and the COVID years. We start at 1984 and run through current days. For its part, 1984 was a major transition year that saw the market showing its belief in the “inflation victory.” The year 1984 was a banner year for GDP growth at a +7.2% annual GDP growth rates. That came after +4.6% in 1983 growth after the Nov 1982 trough.

The 1980s were still somewhat in a world of their own with 8% and 9% yields on the short end in the late 1980s and fed funds returned to just under 10% in 1989 before the credit cycle started unraveling. The fed funds hike late in the decade was another reminder that the Fed was fixated on inflation and viewed strong economies as worrisome. They clearly wanted to get through the cycle without revisiting inflation. With Greenspan at the helm by 1987 and one stock market crash under his belt soon after his arrival, he was focused on not messing up Volcker’s inflation victory. I will look at those 1987-1988 transition years in a separate commentary. The main data points for the 1986 to 1989 path were ongoing hikes in fed funds from 5.875% to 7.3125% around the stock market crash in fall 1987 before slight easing after the crash. Then Greenspan kept tightening to a high of 9.8125% by June 1989. Then life got ugly in the credit markets on the way to bigger trouble after the July 1990 recession began. We will address the economic downturn UST curves and inflation separately. See our earlier cyclical commentaries for flavor.

From the juicy 1980s yields to income starvation in the post-crisis years…

The chart really hammers home the yield drought in the post-crisis ZIRP years and in the Fed’s COVID reaction before the very sharp rise in yields in 2022. The 3M UST has now moved above the post-1983 median while the 5Y UST is knocking on that door. The 1980s clearly presented a distinctly higher set of numbers before Greenspan went all-in from the 1990 recession and kept easing well into the next expansion. He later topped that easing with a serious stretch of mega-easing from 2001 through 2004. We look at those recession reactions and extended accommodation periods in other commentaries and more to come.

We isolate the peak inflation battle years of 1980-1983 in a separate chart below: We break out the swings in UST slope. The volatility in those years requires an “isolation ward” to capture the scale (and maybe some Dramamine). The Hi-Lo range from peak steepness to peak inversion of well over 800 basis points reflects a series of UST curve swing for the ages. We saw several dramatic moves in 1980-1981 before the maximum steepness arrived in the bowels of the later stages of the brutal 1982 recession months. The Volcker strategy targeted monetary aggregates and essentially let fed funds float in a very wide range. The movement was more “fly” than “float” as the pain brought a steep recession to go with a “win” in the inflation battle. That Fed desire for a sustained inflation victory kept playing out on a smaller scale after the double dip recession. I would argue that 1% CPI in 1986 cemented the comfort zone.

A replay of that 1980-1982 pain (a-fib with no d-fib to be found) and volatility is what the Fed fought hard to avoid for the past 4+ decades. The inflation spike is now slashing its way through economies across the globe, so it is hard to make assumption that central banks—and especially the Fed—will go easy on this one. The Germans cannot be too happy given their views on inflation. Meanwhile, the political climate in the US and EU (and the UK in the former EU) is getting uglier each day. The UK is a trainwreck. France is rioting. Italians are facing fascism. Another day in the global markets.

Key Takeaways

The asset allocation conundrum: Short rates in the post-crisis years after 2008 have been a case study in severe financial repression that comes with ZIRP and a few brief period of hikes. As a result, the idea of getting 4% on cash early in 2023 is requiring a period of mental adjustment. The evaporation of any income on cash has been tough on those living on a fixed income and promoted risk taking in retirement funds that did not always play out so well. The idea of so many 3% handle coupons (not YTW) on upper tier HY bonds or 4% on B tier bonds is not feeling so great right now. The 3% to 4% dividends on many REITs makes it more imperative that “you love the name.” The same on MLPs at slightly higher yields. The love does not have to be as strong for BDCs, but the comfort zone needs to be on a solid foundation.

The opportunity cost of foregone coupons or dividend yield are diminished in the curve backdrop. While the upside of stock prices is sacrificed, so is the downside symmetry in a market that has a very wide range of outcome and no shortage of risk aversion scenarios. Cash looks like a much more viable asset allocation alternative these days. As a predictor (vs. cause) of recessions, the inversion of the 3M-5Y has a pretty good track record relative to recession timing. The “credit cycle” has literally been ahead of the curve in terms of framing forward recession risk. The first half of 2007 was an exception.

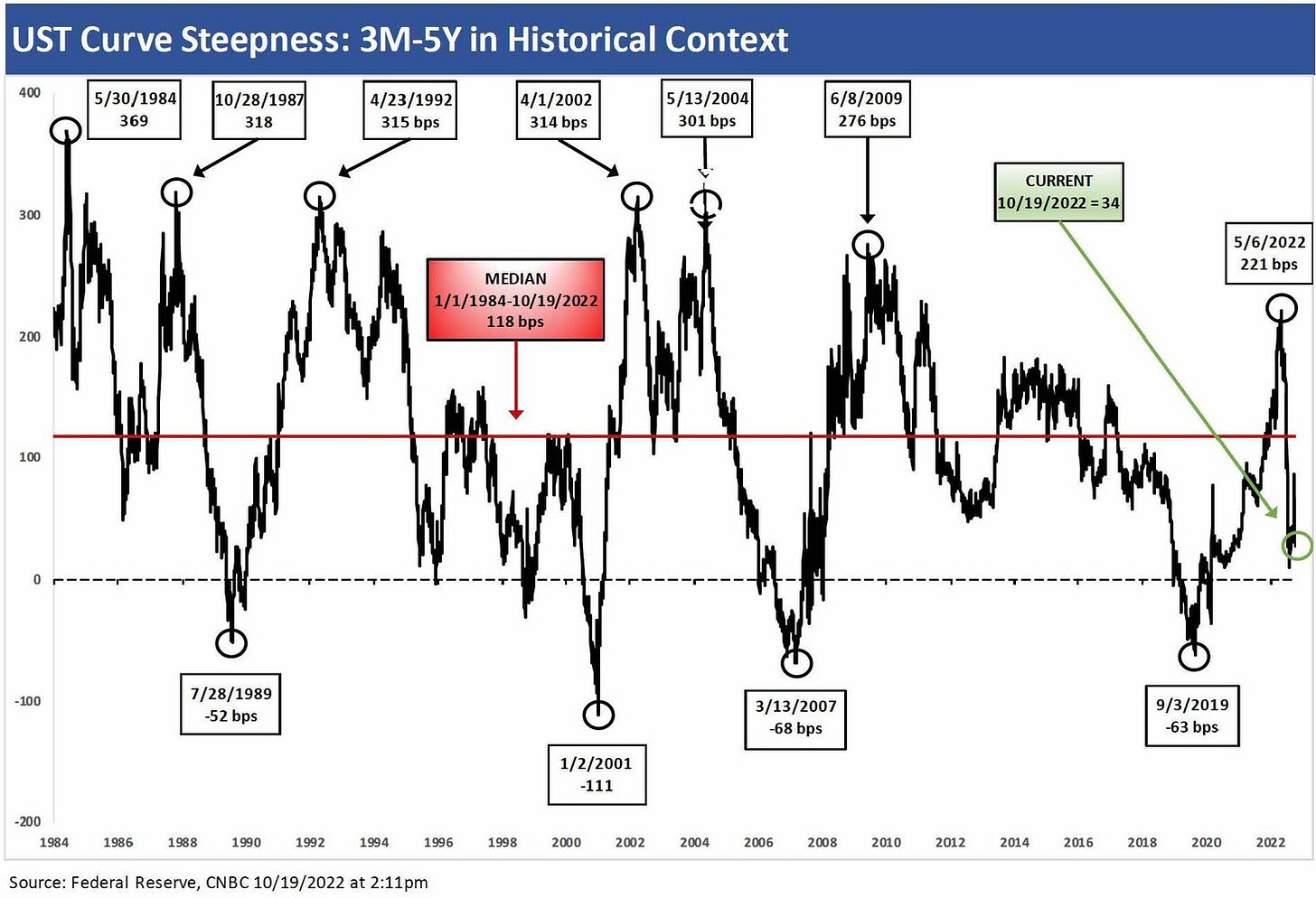

The wild ride of the 3M-5Y UST slope since stagflation years: I break out the 3M-5Y UST slope for 1984 to today in the chart above but break out a separate chart for the madness of the Volcker inflation fighting period. The 1980-1981 period saw rates so high and so steep/inverted in such a short time frame that it impairs the scales and visual effects used to review the following years. Hitting 20% fed funds in 1980 and 1981 was in a class by itself. I look at those periods and fed funds action in more detail in other commentaries.

The combination the charts cover the time frame from the Volcker inflation fighting years of the 1980-1982 double dip recession across the corporate credit boom of the 1980s, the TMT excess years of the 1990s, the housing bubble and structured credit excess of the post-TMT cycle, the credit crisis, and finally the record-long, post-credit-crisis cycle that came crashing down with COVID in 2020. On the bottom of the charts, we highlight material inversions with the date and bps, and on the top of the chart we flag some of the more extreme steepening periods. We see summer 1989, early 2001, early 2007, and later 2019 as highlighted for their 3M-5Y inversion numbers. As we now know, the inversions did come before the recession dates and cyclical hell rode with them eventually. In some cases, hell had already arrived before the inversion (notably 1989, 2001).

The UST curve slope as symptom, not cause: The “inversion as predictor” advocates just need an inversion at any point to be happy. They have had numerous versions beyond the 1Y UST mark already. The inversion buffs can now say that their recession predictor is still perfect when we do have a recession. It is hard not to expect a recession in 2023. If Putin has a pacifist epiphany (not happening) and the China-US economic ties promote a degree of harmony (very unlikely), this cycle might not end up as the shortest since 1980 (the expansion between the first and second leg of the double dip). I would still call the inversion more of a symptom-observer than a predictor. I would rather get into the root causes of the economic illness. Inflation is illness #1 today that will take a toll on the consumer in degrees as it flows into GDP line items in the Personal Consumption Expenditures categories. PCE is still positive but vulnerable. Rising prices have a volume trade-off somewhere in the zero-sum game. Wages are the offset for some but not enough. That “wage-price spiral” phrase is hopefully one that will not come back as common usage like the bad old days of the 1970s.

The swings in UST slope across cycles had some similarities: The typical pattern in very general terms is the UST curve is steep in a trough, then we see rising fed funds and flattening during the expansion to an inversion period of mixed length at different segments of the curve. Then the cyclical turmoil and recession brings heavy Fed easing. The ensuing UST steepening looked similar but presented varied conditions.

The journey from a -52 bps inversion in July 1989 to a peak steepness of +315 bps in April 1992 is typical of the swings we saw in the numerical patterns. From early 2001 (-111 bps) to April 2002 (+314 bps) after the TMT bubble, the market saw a very mild recession but a long default cycle. I would argue that the post-TMT experience was part of a very bad underwriting and origination cycle with a very muted economic downturn.

The systemic credit crisis that unfolded in 2008 saw an inversion at -68 bps in early 2007 to +276 bps by June 2009 across what became the longest postwar recession. The swing in the UST slope before and after COVID was similar to the credit crisis from -63 bps in early Sept 2019 to +221 bps in May 2022.

The 2022 curve rise and the move away from ZIRP is all about inflation: The 2022 curve moves have been heavily influenced by the inflation spike and the lags in the Fed pulling the trigger in the face of inflation. The old rule is that the Fed controls the short end of the curve while the market controls the long end. That is still very much the case despite the occasional Fed actions over the decades to promote a desired bull flattening in programs such as “Operation Twist” and QE.

COVID was clearly a unique event between the inversion of 2019 and steepening of 2022. The market also is trying to frame the effects of the Fed decisions on balance sheet downsizing. The takeaway is that each one of these inversion periods flagged above had a very different lag time and distinct set of economic and capital markets conditions driving the UST curve shape.

Sometimes the inversions “predict” what is already underway fundamentally: I would highlight that for July 1989 and January 2001, the pain in the capital markets was already on the scene and credit quality already under material pressure. The July 1989 inversion (7-25-89) of -52 bps was followed by serious upheavals in the economy and tumultuous markets into what eventually was a July 1990 start to the recession. The year 1989 was especially bad for financial services. The commercial banking sector was getting battered over some regional upheaval such as the oil patch crisis, sporadic commercial real estate corrections and housing downturns across the country. Stress was evident in the securities firms also with hung bridge loans that eventually saw parent company or affiliate bailouts.

As a reminder, the 1989 problems were all back in the Glass Steagall years when there could be material divergence in responses across the capital structure. Bridge loans from brokers and HY bonds could easily become equity risks to support banks asset protection of their loans. After 1989, everything went wrong in 1990 including a Mideast war threat and an oil spike that helped trigger a recession. The July 1990 cyclical peak date (i.e., start of the recession) was only set later in April 1991 by NBER’s Business Cycle Dating Committee (side note: March 1991 was later set as the end of the recession, i.e., the trough). I looked at the quirks of the business cycle dating in an earlier commentary.

Along the way, some events led to more intensive fed support beyond the trough: The regional banking crises of the 1980s were epic in scale (e.g., Texas banks, the thrift crisis in oil patch and later California and across the nation). These localized blowups fueled cross-border consolidation into somewhat of a mega-regional M&A trend including some engineered by the Fed. The Texas meltdown kickstarted the process and regional rollups that gave rise to the NationsBank entity that eventually became BofA/Merrill. I am not looking to do an M&A history recap here, but the regional problems together with the extraordinarily accommodative policies of the Fed went well beyond the official end of the recession. The Fed’s easing into overtime was a major catalyst that ran well into the 1990s and was a catalyst for many thrifts’ branch acquisitions along with many bank deals (notably in Texas). Many were being handled by FDIC deal makers (such as First Republic branches from Texas into NCNB/NationsBank).

As mentioned, the bridge loan pain of the securities industry in 1989 was a major setback, and HY bond market stress peaked after the Drexel bankruptcy in early 1990 as market making was pummeled. In those days, the culture in making markets was often “that was not my deal” in HY underwriting and Drexel was king. That only inflamed problems in secondary liquidity. The passage and just the name of the 1989 FIRREA legislation (Financial Institutions Reform, Recovery and Enforcement Act) hammers home that the UST inversion was less about prediction and more a reflection of current reality. The inversion was just part of a pile of evidence already on the scene.

The 2001 inversion came as defaults were underway and deals failing: The early 2001 inversion came in a year just ahead of a major series of easing actions that seemed more geared to capital markets chaos than a recession that was the mildest in postwar history. The TMT debt cycle brought a level of low quality and lending excess that was in a class by itself even with the bar set very low by the 1980s. That main debate from that easing cycle was that it went too low and went on for too long. The easing sowed the seeds of the housing bubble that came on very quickly.

The post-TMT recession – as muted as it was in terms of GDP contraction – also drove home how asset bubbles and underwriting cycles by banks/brokers can be a major factor in financial repression outcomes. Over the years, the minimal fed funds or even ZIRP severely penalized cash by driving short rates that effectively assure zero or negative real returns. That in turn forces investors to take more risk whether credit risks, equity risk, duration risk, emerging market risk, or in more extreme situations currency risk. That can be at the retail level or institutional level. A steep UST curve with low short rates after a recession also can be an incubator for new products that run the gamut from innovative and prudent to wild eyed to contrived or lead to a situation where the inmates (or math majors) take over the asylum.

The lag effects post-TMT look beyond the reality of expansion: Low and steep UST rates have operated as a catalyst for more aggression. The leveraged product proliferation played out in the structured credit boom after the post-TMT accommodation. For example, the protracted low target Fed funds rate defied the recession cycle dates as Greenspan eased so dramatically after the TMT implosion. The Fed went below 2.0% to 1% handle fed funds around December 2001. That was technically after the official end of the recession as later set by NBER at November 2001. The Fed even moved to as low 1.0% from June 2003 to June 2004. The Fed did not return to a 2% handle until November 2004. That sort of easy credit made life very interesting for mortgage products and new structured product offerings and lent themselves to a lot of leveraging activity. We see multiple steepness peaks along the way in that time horizon out through late 2004.

2007 3M-5Y inversion… bring on the crisis: In the inversion timeline, we then see the early 2007 inversion. For longer segments of the curve (2Y-10Y, 2Y-30Y), we see inversions in 2006 since. In the 10Y and 30Y maturities, that is where the Fed has less control over the process. That is where the market votes. The 2007 inversion of the UST curve in the chart above can lay claim to being predictive. Then again, one can also argue the housing crisis had already arrived with a peak 2005 for builders and some afterburn in the refinancing and mortgage markets into 2006. The corporate credit markets did not call this one yet as HY and leveraged loans boomed. The 2Y-10Y was a better predictor here since that inversion came in late 2006 and 2Y-30Y inversion earlier in 2006. A lot happened after that in the slope including some steepening moments in 2007. In other words, the UST slope sent a batch of mixed signals in 2006-2007. UST predictor advocates are sometimes like venue shoppers in the legal system. They need to pick what fits the need.

The pain in structured credit would unfold very rapidly in the summer of 2007 after a 1H07 stretch that saw record volumes in leveraged finance with tighter pricing to go with record-sized LBOs. NBER later determined (in Dec 2008) that Dec 2007 was the peak of the cycle and the start of a downturn that ran 18 months for the longest postwar recession.

The 2019 inversion was a “no decision” on its predictive value given COVID: The Sept 2019 inversion is interesting since that series of inversions brings a debate around how sustainable the record-long economic expansion was going to be. Of course, that debate could only play out in the absence of COVID slamming the US in force in March 2020 after it very quickly hit Italy in late Feb 2020 and started a US-Europe pandemic. In theory, the -63 bps inversion for 3M-5Y UST in 3Q19 (9-3-19) noted above in the chart was sending recession signals. The 2Y-10Y barely registered inverted in 2019 with negative single digits in the summer. The 2Y-30Y did not invert.

As far as sea level evidence in 2019, the 4Q19 weakness in investment lines showed cyclical pressure at the time. In terms of specifics, the lines that can be viewed as “capex” at the macro level (Gross Private Domestic Investment “GPDI”) posted -6.5% contraction in the GDP accounts. The weakness was most notable in Nonresidential Fixed Asset Investment in Structures (-8.0%) and Equipment (-4.9%). That GPDI contraction was the lowest since 1Q11 or in over 8 years. So clearly late 2019 was facing some headwinds, but those were not recession numbers. Yet.

The 4Q19 total GDP growth line was +1.9% in what ended up as a +2.3% year as the critical PCE line held in well enough. The capital markets were strong entering 2020, but we will never know whether that inversion was on target for a recession flag. We doubt the UST inversion was a mysteriously unknown epidemiological alert system (!) since COVID showed up very quickly in the US. Some (including me) blamed the weak capex unfolding in 2019 as a function of trade battles and some front-loading of spending in 2018 after the tax bill. That gets into the counterfactual game from there. COVID ended the discussion.

In the context of today, the jury is out on what the UST curve is predicting with some pockets of inversion during 2022 and fed funds heading higher with more to come. As we go to print in October, the 3M to 5Y UST is upward sloping while the 2Y to 10Y is inverted as is the 2Y to 30Y. Fed hike forecasts were getting pulled forward in September after the Core CPI number spooked the market and the terminal fed funds numbers were hovering at 4% handles by early 2023. The new target median for the Fed is for a 4.6% terminal rate in 2023. A cross-section of the street is already forecasting 5% handles.