State of Trade: The Big Picture Flows

We detail deficits and import/export history plus major trade partner mix. Protectionism will grow from here.

We get busy on the topic of trade as the US targets China, key trade partners fight with the US over IRA/EV protectionism, the EU looks to try out a carbon border tax, and the WTO has ruled against the US approach to national security tariffs (Section 232).

The complexities of tariffs, quotas, and trade law legalisms/doubletalk does not change the fact that tariffs are a combination of inflationary or earnings dilutive with multiplier effects that can weigh on growth and strain alliances.

Tariff are paid by the importer – not the exporter – even if the mantra of “collecting billions from China” was one of those oft-repeated lies during the tariff wars of recent years.

Trade disputes will loom in 2023 and there is every reason to think they will get worse. Rather than pushing back on Trump tariffs, Biden has held onto many even if most were refashioned from the more insulting (to an ally at least) Section 232 versions (national security) to mutually agreed upon quota-based tariffs. The Section 232 journey of finding a national security threat in numerous key product groups (notably Steel/Aluminum) was dinged by the WTO in recent days as a violation of WTO rules. The strange recent history of the Section 232 strategy is a topic for a separate write-up, but the most important 232 tariffs (those with NATO allies and NAFTA/USMCA partners) had already been addressed in bilateral talks. The US gave the WTO the Bronx Cheer after the Section 232 ruling. National security tariffs remain in place for nations such as China and Russia, among others.

Trying to condense the complexity of trade rules and the leading US role within global export destinations is a daunting task. I started looking back into the histories, documents, and literature as soon as Trump won the election back in 2016. Having followed the autos and industrial names back in the 1980s and 1990s as NAFTA was born (effective 1/1/94 after being signed by GHW Bush and legislated under Clinton), I was thinking in late 2016 that the Trump rhetoric on trade was going to get very interesting and very ugly – and very quickly.

The clashes did bring plenty of escalation and considerable political noise, but it is also important to keep in mind that total trade keeps on climbing and that means more economic activity. The world economy keeps on growing and US trade with it as we detail below in a few charts. As glaring as some headlines can be, it is important not to be too melodramatic given how trade has played out across a credit crisis and a pandemic. As we detail in the chart below, the timeline in trade shows steady growth despite the ups and downs of some shattering economic events.

The chart above tells a story of macro growth with a few stalls along the way. We highlight the pain of the credit crisis and COVID in the boxes on the lower right. The 2008 to 2009 decline in imports and exports was part of the longest recession since the Great Depression. The period of contraction then gave way to the longest postwar US expansion. COVID brought that economic cycle crashing down into the shortest recession in history during early 2020 in a 2-month period (March-April 2020). We break out in the chart how the trend lines for exports and imports increased from the 2020 year of COVID across 2021 and then into the LTM period of Oct 2022. The growth in exports and imports rose sharply in linear fashion across a very strong rebound in 2021 into what is a faltering economy in 2022 with inflation heightened numbers.

US vs. China, the IRA approach to EVs, and the EU carbon tax will be the events of 2023…

Given the reality of how complex and layered the information can be in trade battles, we will try not to overreach as we start publishing on this topic. We will frame the 2023 trade risks in shifts and look at individual topics and trade partner challenges over time. The past few weeks have only made life more complicated with WTO rulings against the US and its use of the National Security rationale for tariffs (“Section 232”), the attempt to institute controls on what technology China can get, and the planned use of a carbon border tax by the EU.

These items are among a handful of disputes that can end of in protracted battles over years. The Section 232 ruling against the US took four years. The headlines on disputes are less important than the timeline to retaliatory tariffs. The quirks of the process are such that appeals can take years before retaliation damage is done – unless the trading party takes immediate retaliatory action not sanctioned by the WTO.

There is a hefty base of trade literature in the markets that got on more radar screens during the Trump years given the setbacks in free trade across so many major economies. The WTO process (or dysfunction) and the trade agreements themselves are tough enough to get one’s arms around on topics such as Most Favored Nation clauses. Then there are always the special interest groups across bilateral trade relationships (e.g., sugar is considered one of the longstanding classic cases of protectionism). For those looking down to the industry and security level, the trick is framing the risks of disruptions ahead, shifts in policy, unit cost threats, loss of market access in major trade zones, and any domestic political risk from the changing mentality of legislators. The obvious topics such as China and the EU are where the big dollar effects lurk in 2023.

Total trade and country share as they stand now…

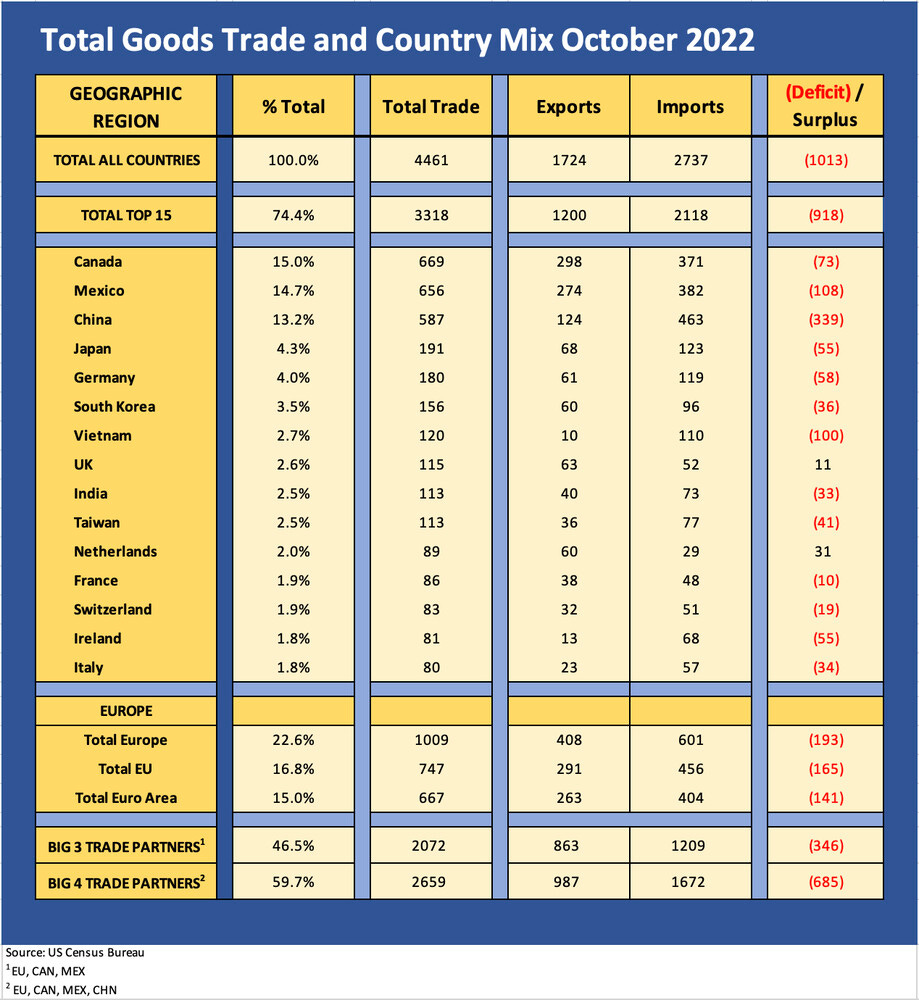

We will start with a top-down view of how the US total trade picture looks currently. The chart below details total trade, exports and imports, and trade partner mix by region/country. As a reminder, “total trade” is the sum of exports + imports. The chart below covers total trade YTD through October 2022 (released Dec 6, 2022). The chart includes total trade with exports and imports broken out. We look at the data for the Top 15 countries and for some slices of the European trade metrics (Europe Total, EU, Euro Area). The chart also details US deficit/surplus by country with the US goods balance in a deficit with 13 of 15 nations in the Top 15.

The most striking aspect of this table is the trade partner concentration across Europe, the NAFTA/USMCA partners (I can’t bring myself to drop the NAFTA yet), and China. If we include Europe in total (vs. EU only), just under 66% of US trade is in those three buckets – Total Europe + NAFTA partners + China. Adjusting for “EU only” within Europe as a trade bloc partner, the share is 59.7% for the Big 4 with the Big 3 (EU, CAN, MEX) at 46.5% of trade YTD Oct 2022.

The Top 15 countries comprise almost 75% of trade. One interesting twist on Europe is that only one EU nation made the Top 10 countries in the form of Germany at 4.0% share. France is under 2.0%. One of the main points of the EU concept and later the Euro Area was to allow those European nations to have the clout of a bigger share of trade and thus have a bigger seat at the table.

Trade kept on climbing through the noise, and that helps calm nerves…

The fact that trade flows have grown alongside the impressive expansion of the US markets across the cycles is no surprise. US nominal GDP doubled in the 1980s, and the 1990s saw explosive growth in technology industries and service sectors. Those decades also brought years of massive expansion of low-cost supplier chains that helped China grow quickly. The global buildout was driven by multiple factors including tapping into favorable secular trends in demand from growth markets such as China with its outsized potential consumer base. There is no hiding from the “labor arb” topic in global planning with the cost differentials of labor being a material multiple on the unit cost side. That is true in Mexico as well as China. That is where America First Right and the Bernie Sanders Left have some commonality of perspective.

The chart shows the longer term growth in trade and offers a soothing reminder of rising economic activity for the US before the debate starts on what trade deficits mean for the US economy. The bounce off the 2020 COVID year lows ran higher for exports and imports in 2021 and into 2022 for an LTM Oct 2022 total trade number of $5.3 trillion. The trend toward more onshoring/re-shoring (return of the supplier chains to the US) or nearshoring (Mexico) carries a need to allow such supplier chain relocations to have economic advantages. The costs must justify such a move but runs counter to the focus on maximizing margins.

From our vantage point, the end game almost has to be one of “hello tariffs and quotas, and goodbye WTO rules” to protect the US and offer incentives for the suppler chain changes. The process could have political incentives where the Democrats can also seek to neutralize the America First pitch while seeking to appeal to the blue-collar constituency where the Dems lost so much ground in the Reagan years.

That said, such changes have to be bipartisan or there will be too much political risk in making those changes. If the tariff strategy gets reversed later, then the reshored or onshored supplier becomes uneconomic. That is unless they can prop up the WTO on some foundation that allows the US (and potentially the EU) to protect their domestic interests (translation: always take care of the home team). The counterpoint is that such strategies have failed through history.

Timelines and cyclical evolution show resilience of trade flows…

The time horizon on the line chart covered earlier in the above section cuts across the original NAFTA deal of the early 1990s, the auto import clashes with Japan, the spike in transplant capacity in North America, and the arrival of more transplant supplier chains to the US/Mexico/Canada. The history also came with waves of global M&A that complicates the analysis. The fact that US companies own many of those imports cloud the approach to narrow domestic onshore interests.

The fits and starts in negotiating trade deals (some were not executed such as the Trans-Pacific Partnership) fleshed out a lot of conflicts across varied interest groups and ideologies (some intra-party for both major parties). The soaring growth of China as a trade partner as global supplier chains took off in the new millennium and US private sector sourcing decisions had a lot to do with it. LCC (low-cost-countries) as a term lost its allure, but there was plenty of that to listen to back during precrisis conference calls – and notably from the auto sector. Back in the pre-crisis years, many companies would have presentation slide pages on their China expansion programs. We don’t see those too often these days as something to highlight.

The supplier chain buildouts globally were part of a trend including European operators. The US just moved very quickly and on a grand scale. We see that further below in the trade deficits bar chart. The pace of goods trade deficits occurred in many aspects by design and were in part driven by US private sector investment in JVs in China. In addition, the regional supplier chains offered a range of comparative advantages to supply US manufacturers (sometimes via Mexico or Canada for assembly). That creativity is how many companies did so well on a global scale by optimizing unit costs. Unwinding that supplier evolution cannot be done from the White House podium. The economic equation could change supplier planning via more tariffs and quotas. That is what some policy architects are debating currently.

Trade and tariff battles for the US fixated on trade deficits…

Since the US has so many material trade deficits by country, the US is the main event in the next evolution of global trade. The EU is the #1 trade partner of the US. That creates some unusual dynamics set against the backdrop of Russia-Ukraine and China throwing tacit support behind Russia. The EU and US need to play nice with each other. The game theory there is for another day. National security might be legit for the next wave of tariffs – regardless of what the WTO thinks.

Some of the debates on the trade deficit topic stumbled into the land of conceptually bereft back in 2016-2020 and took on more ideological tones. You could flunk intro economics on some of the stances taken. The idea that political necessity outweighs basic economic theory (and business P&L analysis) is not new. This may still play out over the next few years. That zero-sum game was just not as well dressed up in the first wave of protectionist fervor in 2018-2019. The latest protectionist approach has more lipstick and more bows on it.

The timeline on US trade deficits is plotted above. The important takeaway is that the growth of that deficit has many different aspects to it. Simplifying those deficits whether in total or by country is usually done for a political and policy reason to cater to a constituency that involves getting votes or money. Slapping tariffs on steel and aluminum hurt many companies and employers, and that has been picked over by think tanks publishing their studies. Once those tariffs are on, however, they are hard to take off. Cost pressures on importers and inflation is the logical outcome.

Balanced views or an accurate accounting of tariff history would depart from the rule of thumb of “simplify messages and repeat them over and over again.” That was the case with the tariff waves in 2018-2019. The tariffs were inflationary and COVID made everything worse. Some of the messages spun on the tariffs are quite true (e.g., unfair trade practices by China are overwhelmingly documented). Some are purely intentional misstatements (or do business school call those “strategic misrepresentations”?) such as the Section 232 claims. Some are misleading by omission.

The fact remains that when the US economy does well, trade deficits go higher as more gets consumed. Some loss of manufacturing is secular, but some manufacturing subsectors could return in part if protected by tariffs that target select countries (e.g., China). That cannot be the formal pitch, however, since it runs afoul of a multilateral body the US basically designed (the WTO).

For some, the best move would be to “cut your losses, and just kill the WTO by a thousand cuts.” That seem to be what’s playing out now. The IRA is one recent example of protectionism and there is more to come. The brute force Section 232 tariffs did not work. Retaliation was the response, and capex was stalled and profitability impaired for many. The political playbook will be unfolding in 2023 on how to grab the mantle of “friend of the US worker.”

There is a lot of point-counterpoint on how trade deficits grew so large or “got so bad” in a few decades depending on what you choose as a starting point. We don’t see trade deficits as intrinsically bad at all. For that matter, not all tariffs are bad.

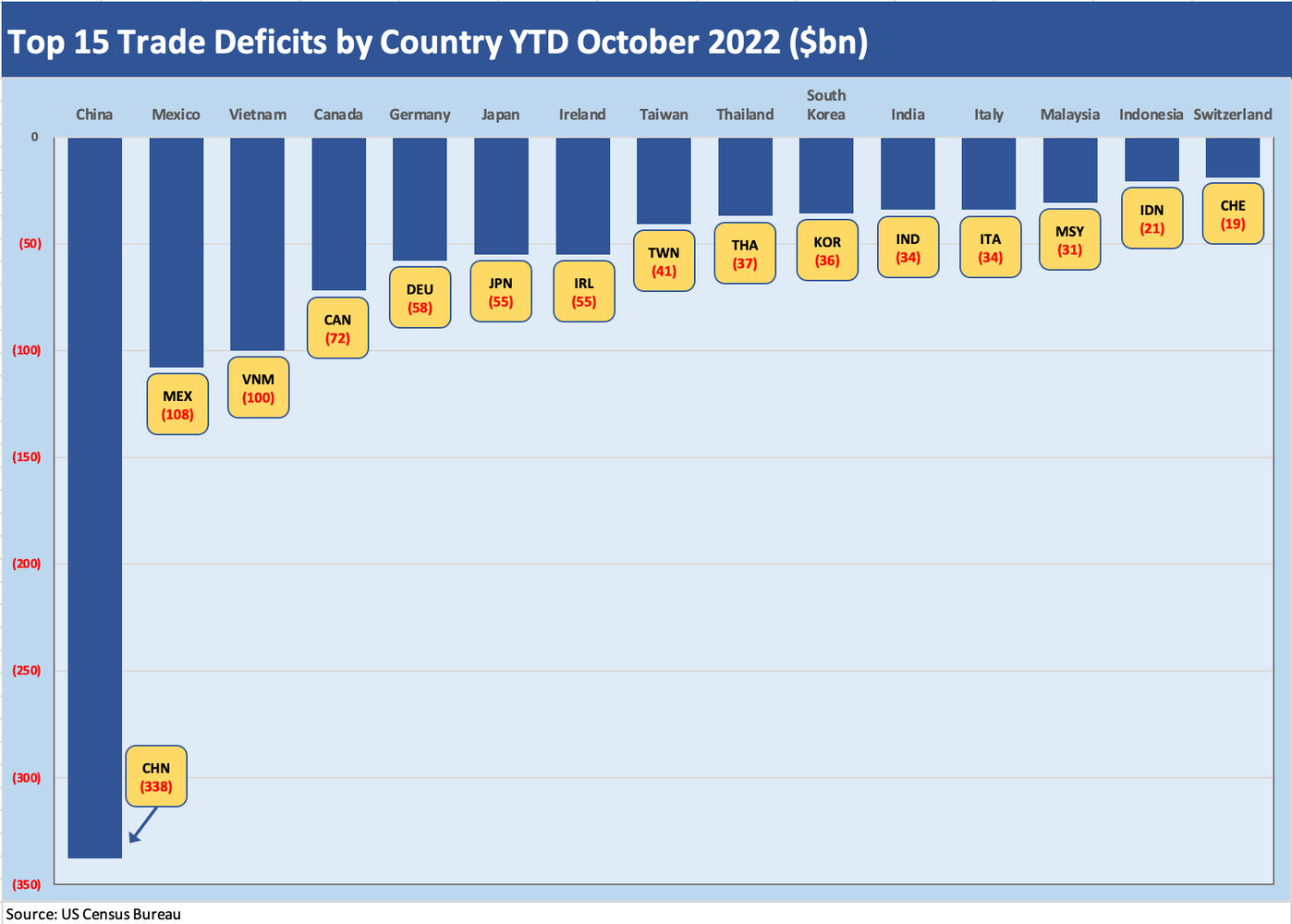

If we just roll the trade partner deficit mix forward to YTD 2022, the above chart shows the rankings of the Top 15 largest trade deficits in goods (note: the US runs a regular surplus in services globally). The nature of these deficits (product mix, etc.) are for another day and other commentaries. The China deficit is down from the peak as tariffs took their toll on various line items where low cost substitutes could be found.

The China-US goods trade deficit peaked (calendar year basis) at $420 billion in 2018 before the most aggressive tariff battles and a semi-truce took it down to around $346 billion at year end 2019. We would expect the year end numbers for 2022 to remain well ahead of the 2019 numbers but below 2018. These trade deficits are often a function of embedded supplier chains that do not have easy alternatives. The challenge is that some decline in broad categories can be achieved, but many product groups (auto parts and cap goods components, electronics, etc.) are not so easy to relocate.

The tense geopolitics can spill over into longer term planning by China as well. The use of sanctions on Russia in the Ukraine war has not been lost on China. The more the US clashes with China, the more China needs to find alternative supply sources (hitting the US export line) or alternative customers (redirecting some of their resources to other end markets). That can have the effect of China pulling back exports where US-based employers would prefer they did not. That extends beyond agriculture and energy. That can also impact prices on suppliers that have limited capacity.

The clashes ahead are more political and subjective…

The issues around trade can be easily extrapolated to protectionist Armageddon if one if so inclined, but history shows trade keeps on growing. After the brutal “diplomacy” of 2018-2019, the tit-for-tat tariff battles with major trading partners, and the very strained relationships with those trade partners essentially tagged as national security threats (notably the EU, but also Canada/Mexico), the backdrop had calmed down during COVID.

The world faced much bigger problems on supply, freight, and logistics during COVID. The latest events make tariffs seems trivial as the largest land war in Europe since 1945 continues with waves of sanctions. Debating fair trade started to look secondary to undermining “enemies.”

As we cover earlier in this commentary, US trade with the world kept on growing in 2021-2022 off the 2020 COVID lows. That can be looked at country-by-country and product by product category. The theme of the China-US decoupling gets a lot of airtime, as does the meaning behind the trade sourcing reallocation. Decoupling does not come at low cost to importers or at low cost to global geopolitical uncertainty. Auto parts, tech-centric products, and medical/pharma supplies are much harder to “friendshore” than cheap T-shirts, footwear, and textiles.

The question will be to what extent economic analysis will be more objective and truthful this time around and how much will be about pure politics and interest group gaming.