Pension Plan Drain Rates: Plan Benefit Payments % Plan Assets

We look at some notable corporate defined benefit plans to frame the cash flow challenge of funding current benefit payments.

We frame some pension plan drain rates and see more than a few 8% rates (and higher) in major plans, which means a need to focus on more cash-flow-based investing.

A wide swath of pension plan sponsors face drain rates higher than the par weighted coupons of the IG index (~3.8%) and the same for many vs. the HY index par weighted coupon (~5.8%).

We see the topic as an interesting one for the asset allocation challenge and see the demand for credit risk (in some form or subsector) as staying high just out of cash flow necessity.

In this commentary, we look at a selection of pension plan drain rates for a relative handful of notable corporate sector defined benefit plans. We frame beginning and ending assets and payout ratios in what was a very bad year for pension plan asset declines. Whether assets go down or up, the realities of recurring pension benefit payments remain the same. That requires a very high rate of cash generation whether income flows or monetizing assets. The problem with selling into choppy markets is that the timing might be bad for selling stocks into weakness. Furthermore, many assets in the plan mix might be illiquid. That is where credit risk and debt and cash flow generation come in.

In a world that until recently was starved for income (e.g., from .01% deposit rates to 4% handle ones now and money market funds climbing), there are a lot more options today. That said, the cash flow demands of benefit payouts to retirees are quite high for many companies with defined benefit plans. The same is true for many public sector plans where the disclosure is much harder to come by.

This note is just a quick visit to the topic as 10Ks roll in. We will be looking at these topics in more detail from different angles as the disclosure is available. For the dozen plans below, we look at some of the largest pension plans in Aero & Defense, Autos, Telecom, and a bellwether Airline among the more recognized industries exposed to pension risks. The same exercise can be replayed for any plan.

The big asset declines are no mystery. We show the benefit payments for year end. We then divide that payment by ending assets.

We see some very hefty pension plan payout rates with nine of them at 8% or higher and one in double-digits (AT&T). As a frame of reference, the par weighted coupon in the US HY index (ICE BofA) is 5.8% and the IG Index is 3.76%. That means a 100% HY portfolio would fall short in cash flow (of course, that would not be a sound or prudent, diversified portfolio. We were making a point).

Pensions and the coupon problem…

The asset allocation challenge for pension portfolios is rooted in multiple refinancing waves set against ZIRP and flattening curves during the credit crisis and COVID periods. Coupons are low and we just came out of the most pronounced and rapid upward shift in the post-Volcker UST bond markets. With all those low coupons, the par weighted dollar price of the IG index is around 90 and the same for the BBB and BB tier. The BB heavy US HY index is just under 88.

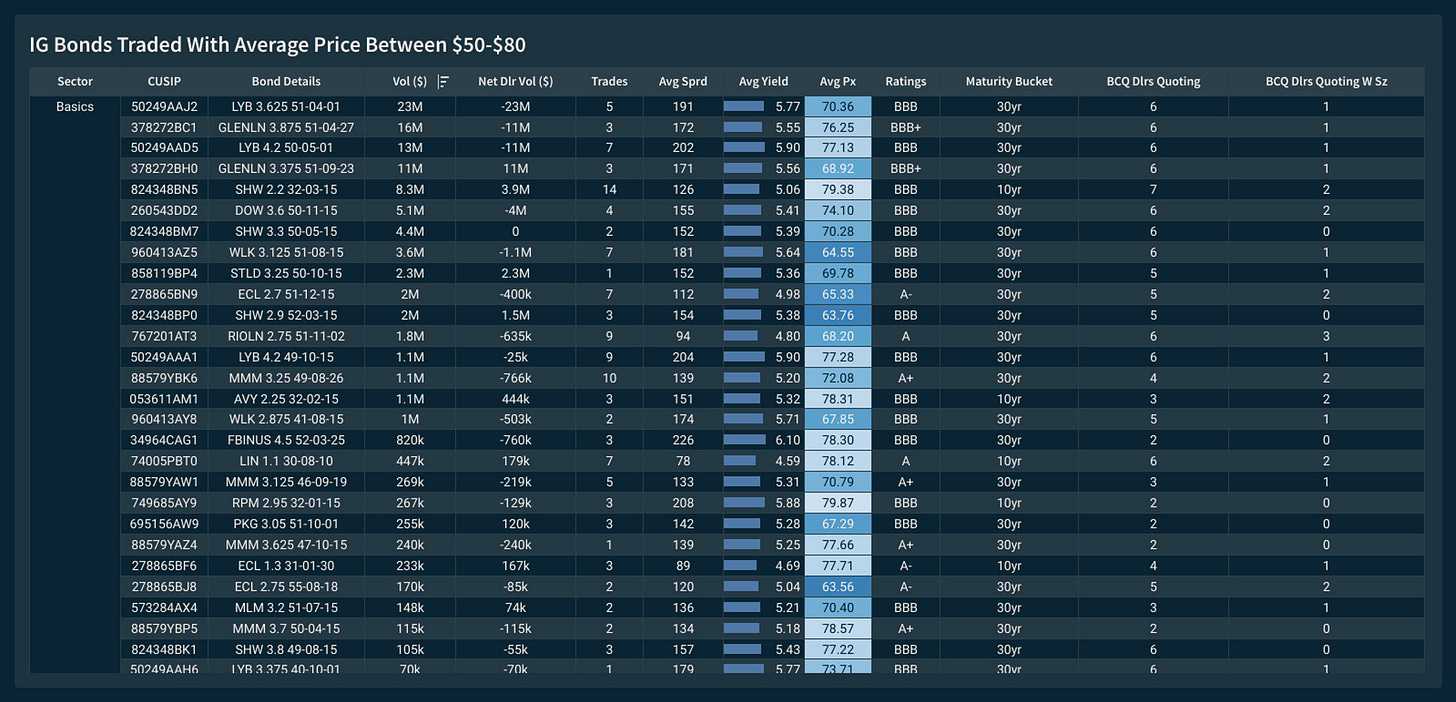

The reality of the steep discounts is represented in the trading flows reported below compliments of BondCliQ, who has oceans of data from trading activity every day. The chart below is just a cut/paste sample. You should log into BondCliQ for a dynamic version of their discount data and related charts.

We get a sense of some names trading in the 50-80 range. The steep discounts get into the questions of “How do you like your yields served” whether by coupon income or via longer term dollar price accretion. For many pension funds, current income matters a lot at this point. For some other investor segments, the tax questions are distinct to any given portfolio mix.

Source: BondCliQ

The UST curve shock has changed the world of dollar prices and the mix of cash vs. price returns in the IG and HY market. That is a different prism to look through after waves of refinancing in the post-ZIRP, back-the-future inflation world. For major pensions, we would expect in this market to see more allocations to leveraged loans and increased flow of private credit pitchbooks showing up on desks from mid and large cap holdings down to small and microcap borrowers. There is a reason more BDCs are growing and issuing equity to support their asset growth.

Drain rates as an asset allocation X factor…

The focus on stocks and high expected plan asset returns in “the old days” of pension investing gave way to higher mix of corporate bonds for multiple reasons. For some, it was a function of derisking. Derisking themes are based on declining rates raising present values of obligations. In turn, declining rates drive fixed income bonds to outperform on the asset side. If rates go higher, bond valuations get hurt but the liability math gets better.

While pension investing is a lot more complicated than that, the “derisking wave” often frames asset-liability dynamics as the short version with companies such as GM, Ford, and Goodyear (shown above) actively pursuing that strategy. They have exceptionally high and outsized bond allocations.

Other derisking strategies involve risk transfer to insurance companies. Those are topics for another day, and plan sponsors have shed many billions via these pension risk transfer strategies in recent years.

The pension footnotes are busy neighborhoods…

As wrap-up comments, a lot of information is stacked into the multi-page pension footnote in the 10K. There is the reconciliation of the projected benefit obligation (this is where the GAAP measurement and accounting quality come into play on assumptions), the plan asset moving parts (returns, benefit payments, various adjustments), and the income statement reconciliation (the expected return assumption is basically a contra-expense line). Most importantly, the details on the actual asset mix and target range of asset allocation are in the footnote.

For purposes of this note, we were not looking at any of the measurement or accounting quality twists and turns that often get debated (return on asset assumptions, discount rates, etc.). The going rate on expected plan asset returns in the above plans is around 6% but we see 7.5% on the high end and 4.2% (Goodyear with its almost all-bond strategy) on the low end.

We are not looking at shifting legislation, legal risks, the role of the PBGC, and what GAAP books mean as they contrast with the ERISA books. We are not looking at the funding legislation that eased demands for pension plans around the radical UST curve shifts. The UST curve shifts during crises would have had the effect of spiking funding requirements. Washington came to the rescue.

As a general trend, the legislative priorities migrated from trying to shore up funding before the credit crisis to helping provide relief to the companies. The goal was to keep companies out of liquidity stress and to avoid labor clashes if more plan sponsors started freezing plans.

In this piece, we also are not framing the pension underfunding exposure as a balance sheet risk or how any of those could flow into modified valuation metrics such as Pension Adjusted EV/EBITDAP. That is a favorite metric for some and worth being aware of, but our experience has been that it gets ignored in the end. It is certainly relevant for industries such as Auto Parts. Those types of issues are for other days and more tables and charts.